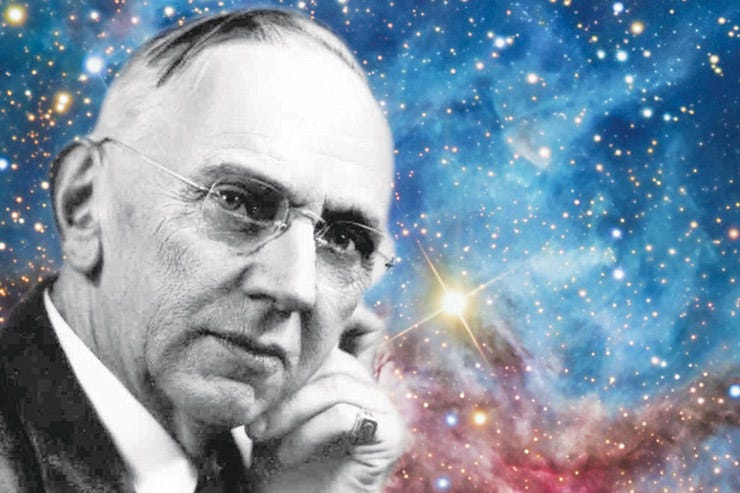

The Messenger

How Edgar Cayce became reluctant prophet of the New Age

Since Biblical tellings of Moses refusing Yahweh’s entreaties to return to Egypt, prophets in the Abrahamic tradition are often framed as reluctant figures summoned from ordinary lives to assume missions unsought.

If the New Age—the radically ecumenical culture of therapeutic spirituality that swept Western life beginning in the early twentieth century—can be said to possess a founding prophet, it appeared in such a figure: Sunday-school teacher, farmer’s son, and commercial photographer Edgar Cayce (1877-1945).

Through psychical readings and warmth of persona, this messenger of religious eclecticism, mind-body medicine, and accessible esotericism did more than any single figure to define the culture of alternative spirituality.

In Cayce’s lifetime, world-traveled seeker Madame H.P. Blavatsky (1831-1891) brought occultism and Eastern mysticism into Western awareness. Dean of esoteric studies Manly P. Hall (1901-1990) curated a codex of symbolist and mythical teachings. Teachers including G.I. Gurdjieff (1866-1949) and Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) articulated comprehensive esoteric philosophies. But it fell to Cayce (pronounced casey)—psychic, medical clairvoyant, and uneasy mystic—to transplant ageless mysteries into American living rooms.

From 1901 until his death on January 3, 1945—the seer died at just sixty-seven—Cayce produced more than 14,300 clairvoyant readings, many recorded by stenographer Gladys Davis. His trance-based readings, delivered to people across the nation, popularized a catalog of occult themes from reincarnation and numerology to astrology and channeling. The last term, now ubiquitous, entered modern idiom through Cayce’s coinage.

What’s more, the psychic’s communiques exposed everyday people to holistic medicine, natural remedies, and—in a modern first, or nearly—therapeutic use of meditation. Cayce’s readings kindled interest in Atlantis, lost epochs and civilizations, and “earth change” prophecies that posited dramatic shifts in our ecosystem. These rarely met target dates.

Although Cayce attained prominence in the early twentieth century and died shortly before World War II ended, his career and teachings experienced resurgent appeal in the 1950s and beyond, touching Beat culture, the Woodstock Generation, and the nascent recovery movement.

Not every twentieth-century seeker was prepared to enter Blavatsky’s sprawling 1888 opus, The Secret Doctrine. Most had not yet heard of Hall’s 1928 epic, The Secret Teachings of All Ages. Gurdjieff, Steiner, and other esoteric teachers required signal effort. But Cayce, in person and style, proved gettable.

The approachable man—warm, bewildered, idealistic, generous, devoutly religious, and dogged by career obstacles—won a mantle he neither sought nor claimed: founding father of the New Age.

“Help the sick”

Cayce was born on March 18, 1877, in Western Kentucky. His town of Beverly did not see its first paved road until 1932. Tobacco was the major crop, and nearly everyone owned farmland or worked for someone who did. Cayce’s father, Leslie, was a tenant farmer.

Although childhood could be harsh—Leslie was known to drink and sometimes mete out beatings—there appeared unmistakable closeness and trust in the family. Even when Edgar was well into middle age, his father addressed him in letters as “My Dear Sweet Precious Boy.” Of Cayce’s mother, Carrie, little is known between her personal quietude and dedication to Scripture.

In this insular world—church-based, segregated, agrarian—Cayce grew up a sensitive, awkward child. Thin and tall for his age, he liked playing and spending time alone and was given to wandering through meadows and woodlands that surrounded his home. Adults found him distracted and distant.

The boy reported visitations from fairylike “friends” and communications with dead relatives. At age nine, when classmates took up fishing or sports, Cayce grew engrossed with Scripture and begged his father—a man never quite possessed of steady work—to buy a Bible for their home. Edgar began reading it through each year.

One night at age thirteen, this boy who talked with hidden friends and consumed the King James Bible, knelt by his bed and prayed for the ability to help to others. Just before drifting to sleep, he recalled in his memoirs, a glorious light filled the room and a feminine apparition appeared at the foot of his bed, saying: Thy prayers are heard. You will have your wish. Remain faithful. Be true to yourself. Help the sick, the afflicted.

Cayce discovered his capacity for trance readings in 1901. Stricken by chronic laryngitis, he entered a hypnotic state and self-diagnosed, directing increased circulation to his larynx, after which his voice was said to abruptly resume.

In years ahead, Cayce worked on the margins of mainstream medicine—with hypnotists, osteopaths, and homeopaths—entering trance states, first under the guidance of hypnotists and later on his own, to prescribe folk cures, natural remedies, and conventional treatments for hundreds and eventually thousands of ill people.

I have family members who use Cayce treatments today, such as castor-oil packs for healing scar tissue and reducing inflammation, meditation for stress reduction (which Cayce popularized), and Pennsylvania Crude Oil for hair growth and dandruff. About twenty-five years ago, I received a computerized astrological reading based on Cayce’s principles; it forecast career opportunities in occult publishing, a field I thrived in.

Amid glowing testimonies, journalists and medical investigators began paying attention. Heralding Cayce’s emergence as a public figure, The New York Times on October 9, 1910 ran an extended profile: “Illiterate Man Becomes a Doctor When Hypnotized.” Cayce was not illiterate, but neither was he well educated. He never made it beyond the eighth grade of a rural schoolhouse. Although he taught Sunday school at his Disciples of Christ church, he read little beyond Scripture, which he completed in yearly cycles.

In some respects, the year of the Times article, 1910, reflected a generational turnover in metaphysical culture. That year saw the deaths of key voices of nineteenth-century spirituality: philosopher William James, Spiritualist pioneer Andrew Jackson Davis, and Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy.

By his public emergence, Cayce had abandoned third-party hypnotists and assumed a self-directed, twice-daily routine trance reading. It consisted of reclining on a sofa or day bed, loosening tie, belt, cuffs, and shoelaces, and entering a somnambulant state; once given the name and location of his subject, the “sleeping prophet” was said to gain insight into the person’s body, maladies, and—increasingly—psychology and past incarnations.

Fees were modest and uneven, leaving the seer this much in common with father Leslie: a lifetime of unsteady finances. Whenever cynics sought evidence of religious profiteering, none appeared in Cayce’s world.

Discussing Cayce on Ancient Aliens

New Age Dawning

In the 1920s, Cayce’s trance routine expanded beyond medicine—which nonetheless remained central—to include “life readings,” exploring a subject’s inner conflicts and psyche. In these sessions, Cayce often referenced astrology, karma, numerology, reincarnation, and like themes. Other times, he expounded on global prophecies, climate or geological changes, and the lost history of mythical cultures, including Atlantis and Lemuria.

Cayce had no recollection of any of this when he awoke, though as a devout Christian the esotericism of such material made him wince when he read stenographic transcripts. From where, he wondered, did these occult topics emerge?

While Cayce’s knowledge of Scripture was encyclopedic, his reading tastes were limited. Most of his spiritual insights reflect terms and tones of the King James Bible. Some of his themes, critics noted, echoed popular occult literature of the day, such as the 1908 “lost book” of Scripture, The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ channeled by former Civil War chaplain Levi H. Dowling. In it, the Son of Man traverses different cultures as a unifying avatar of world religion.

Aside from a few on-and-off years in Texas unsuccessfully using his psychical abilities to strike oil—Cayce sought to finance a hospital based on his clairvoyant cures—the psychic rarely ventured beyond the Bible Belt environs of his childhood. On two occasions of travel—to New York in 1931 and Detroit in 1935—he was arrested and briefly detained: in New York for violating anti-fortunetelling laws (an extant and likely unconstitutional statute) and in Detroit for unlicensed medical practice.

One of the few places Cayce enjoyed respite, during Thanksgiving and other holidays, was at the Scarsdale, New York, home of David Kahn, whose Jewish family of grocers befriended the seer in Lexington, Kentucky. Kahn later grew wealthy manufacturing wooden cabinets for home radios, a booming sector in the 1920s. The former retailer credited his success to Cayce’s psychical insight. Their bond highlights a throughline of openness in Cayce’s relationships, extending not only to religion but sexual orientation. Cayce corresponded encouragingly with a gay cousin in the 1930s. For a child of post-Civil War agrarianism, this is notable.

Universal Teacher

Following his failed oil endeavors, Cayce in 1923 returned to his family in Selma, Alabama, where he resumed work as a commercial photographer. He and Gertrude, who had long suffered her husband’s absences and chaotic finances, enrolled their son Hugh Lynn, then sixteen, in Selma High School. The family, now including five-year-old Edgar Evans, settled into a new home and seemed on the brink of domestic normalcy.

Although no record survives, existence could only have been lonely for Gertrude. Her husband’s psychical activities in a religiously conservative area were not easily shared with neighbors—or inviting of new friendships.

The family’s attempted stability got upturned once more in September when a wealthy Ohio printer and Theosophist named Arthur Lammers entered Cayce’s life. Lammers learned of Cayce during the psychic’s oil-prospecting days. He showed up at his Selma photo studio with an intriguing proposition.

Lammers was both hard-driving businessman and avid seeker in Theosophy, ancient religions, and occultism. He impressed upon Cayce that the seer could use his psychical powers for more than medical diagnoses. Lammers wanted Cayce to probe the secrets of the ages. The Ohio seeker yearned to understand the meaning of the pyramids, astrology, alchemy, the “Etheric World,” reincarnation, and the mystery religions of antiquity. He felt certain that Cayce’s readings could part the veil.

Although commonly described as humble, Cayce was not without aspiration. After years of stalled progress in his professional life, he grew enticed by this new mission. Lammers urged Cayce to follow him back Dayton, where he promised to place the Cayce family in a new home and financially care for them. Cayce agreed, and uprooted Gertrude and younger son, Edgar Evans. Hugh Lynn remained with friends in Selma to finish high school.

Lammers’ financial commitments proved elusive, and Cayce’s Dayton years became another period of financial despair. Nonetheless, for Cayce, if not his loved ones, Dayton also marked a stage of unprecedented discovery.

Cayce and Lammers began their exploration at a downtown hotel on October 11, 1923. Before several onlookers, the printer asked Cayce to give him an astrological reading. Whatever hesitancies the waking Cayce evinced over arcana vanished while entranced. Cayce expounded on the validity of astrology even as “the Source”—what Cayce called the ethereal intelligence behind his readings—alluded to errors in the Western model.

Toward the end of the reading, Cayce almost casually tossed off that it was Lammers’ “third appearance on this [earthly] plane. He was once a monk.” It was an unmistakable reference to reincarnation—exactly the type of insight Cayce’s sponsor sought. Whether the psychic was influenced by expectation is unknown. Paranormal researcher Martin Ebon, a canny and sympathetic critic, wrote in his 1968 Prophecy in our Time that Cayce evinced “the weakness . . . to give in to the demanding questions of the True Believers, to those who wanted to see him as all-knowing.”

In future weeks, the men continued their readings, probing Hermetic and esoteric spirituality. From a trance state on October 18, Cayce laid out for Lammers what could be seen as an overall philosophy of life, encompassing karmic rebirth, man’s role in the cosmic order, and the circuitous nature of existence.

Cayce’s statements are adapted by journalist Thomas Sugrue, who is soon met. They are, it must be noted, rendered more fluidly than the stop-and-start, often choppy language of the readings.

In this we see the plan of development of those individuals set upon this plane, meaning the ability (as would be manifested from the physical) to enter again into the presence of the Creator and become a full part of that creation.

Insofar as this entity is concerned, this is the third appearance on this plane, and before this one, as the monk. We see glimpses in the life of the entity now as were shown in the monk, in his mode of living.

The body is only the vehicle ever of that spirit and soul that waft through all times and ever remain the same.

These utterances were, for Lammers, a theory of eternal recurrence, or reincarnation, that identified human destiny as inner refinement through karmic cycles of rebirth, then reintegration with the source of Creation. This, the printer believed, was the meaning behind the Scriptural injunction to be “born again” in order to “enter the kingdom of Heaven.”

“It opens up the door,” Lammers told Cayce, as recounted by Sugrue. “It’s like finding the secret chamber of the Great Pyramid.”

He insisted that the doctrine that came through the readings synchronized the wisdom traditions: “It’s Hermetic, it’s Pythagorean, it’s Jewish, it’s Christian!” Cayce was unsure.

“The important thing,” Lammers reassured him, “is that the basic system which runs through all the mystery traditions, whether they come from Tibet or the pyramids of Egypt, is backed up by you. It’s actually the right system . . . It not only agrees with the best ethics of religion and society, it is the source of them.”

Lammers’ enthusiasms aside, the religious ideas that emerged from Cayce’s readings did articulate a consistent theology. Cayce’s teachings married a Christian moral outlook with the cycles of karma and reincarnation central to Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as the Hermetic concept of individual as extension of the mind of creation.

Cayce’s references to causative powers of psyche—”the spiritual is the life; the mental is the builder; the physical is the result”—wed his cosmic philosophy with tenets of New Thought, Christian Science, and mental healing. If there exists an inner philosophy unifying the historic faiths, a common New-Age theme, Cayce articulated a persuasive variant.

Past-Life Seer

In Dayton, Cayce delved more fully into readings on “past lives.” Those he found were rarely ordinary. Subjects were often identified as having been ancient priests or priestesses, denizens of lost civilizations, historic kings and warriors.

The figures that populated Cayce’s past-life catalog took forms and personas similar to those from a project initiated several years earlier by English Theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater (1854-1934).

Both Cayce and Leadbeater attributed their material to the same source. Cayce said he was able to access cosmic records imprinted on akasha, or universal ether. These “akashic records” were a Vedic concept popularized in the late-nineteenth century by Madame Blavatsky. Cayce, in his Christian worldview, equated akasha with the Book of Life.

In another effort to synthesize spiritual strains, Cayce on four occasions reported visits from a mysterious, turbaned adept from the East, one of Blavatsky’s Mahatmas, or great souls, whom the storied occultist said had guided her.

Leadbeater’s venture into the past began in 1909 when he discovered an unusual, sensitive boy, Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986), playing on the beach near Theosophy’s headquarters in Adyar, India. Leadbeater saw the teen as incarnation of a new “World Teacher.” Blavatsky’s protege Annie Besant (1847-1933)—the most formidable figure of early twentieth-century occultism—agreed. Krishnamurti did, after breaking with Theosophy, become a deeply respected and unclassifiable spiritual teacher.

In 1910, Leadbeater began constructing an encyclopedic timeline of the past lives of Krishnamurti and his circle. Krishnamurti and his historical companions composed temple hierarchies of mythical Atlantis and Ancient Egypt and left their marks as statesmen, alchemists, warriors, and philosophers. In a sense, Leadbeater created a dramatic prehistory for the lives of fellow Theosophists. A critic might say, not without justice, if you want to win someone over, canonize them.

Cayce’s readings favored similar historical settings and characters: Atlantis and the cities of Hellenic and pre-Columbian empires. Past lives were not without tragedy. Amid the Egyptian princes and princesses, Hellenic conquerors, and Atlantean priests were victims of war, rape, and other brutalities—sufferings that, in the philosophy of the readings, produced present-day neuroses.

The Cayce family (in its twentieth-century version) proved a case in point. In his biography by journalist A. Robert Smith, Cayce’s elder son, Hugh Lynn, made the startlingly frank admission that throughout his teenage years he experienced profound sexual longings for his mother.

This reached a head in 1923 when the high schooler traveled to Dayton to rejoin his family for a troubling Christmas. When his father came to pick him up at the train station, Hugh Lynn hugged him and felt the crinkle of paper: Edgar had stuffed newspaper into his thin overcoat to protect him from the cold of the Midwest winter.

Lammers, it seemed, had experienced a run of business setbacks and left the Cayces destitute. Their promised home was a two-room efficiency, stifling quarters for a young family. The Cayces’ Christmas dinner consisted of a chicken that could be cupped in the hands. While enmeshed in out-of-town lawsuits, the searcher for truth Lammers had neglected to send Edgar even a few dollars for groceries. That is a damningly common parable of the search—and likely more revealing than anything the men discovered spiritually.

Another unsettling discovery for Hugh Lynn, the teen who had stood so solidly behind his father—Edgar’s readings reportedly cured him of blindness at age six following a flash-powder accident—was hearing him enthuse over his new psychical forays into past lives. As a Christmas gift, Edgar explained, he had secretly performed one for Hugh Lynn, discovering that the youth had once been a great ruler in Egypt. Even by Cayce standards, the family seemed to have slid off the edge.

But as Hugh Lynn listened to his reading, his incredulity softened. Edgar’s analysis assumed eerily familiar tones of the youth’s innermost conflicts: his agonizing attraction toward his mother and his jealousy and resentment of Edgar.

Hugh Lynn, his father said, had been an Egyptian monarch who coveted a beautiful dancer, Isis. But Isis’s affections were for the kingdom’s high priest, Ra Ta, with whom she had a daughter. Infuriated, the ruler exiled both. The high priest, Edgar said, was an earlier incarnation of Hugh Lynn’s father, and the dancer Isis represented the past life of his mother.

Hugh Lynn was stunned. He had taken every measure to conceal his feelings. But here was a karmic psychodrama reframing his agony in mythical or archetypal terms.

In its way, Hugh Lynn said, the story brought him a measure of peace. “The reading explained very clearly that what I felt for my father and for my mother was memory,” he told his biographer:

And I was responsible for what kind of memory I had. I was imposing on my father a whole set of ideas that didn’t exist. I was jealous of him, but I had no right to be jealous in the present-day situation . . . You see, I was putting on him my own weaknesses, my own problems—and we all do it.

Although Hugh Lynn emerged as a canny manager of his father’s legacy and business interests, there is no mistaking the sincerity and vulnerability of his disclosures.

Whatever their source, Edgar’s hundreds of past-life readings often provided a sense of context and meaning that helped resolve feelings of helplessness and anguish in the lives of recipients, many of whom returned for multiple sessions.

The catalog of past-life readings also prefigured themes that animate Jungian and transpersonal therapies and the work of mythologists such as Joseph Campbell and Robert Bly. Stripped of occult methodology, the insights of the Cayce readings echoed Freudian theories of repression and neurosis. As I have documented elsewhere, Freud was not without sympathy for parapsychological methods in the analyst’s office.

Scholar of religion J. Gordon Melton, writing in 1994 in Syzygy: Journal of Alternative Religion and Culture, viewed the readings as parabolic versus actual—and bound to familiar themes:

The understanding of the reincarnation material as symbolic, not literal, does much to explain the repetition in the Cayce readings. When Cayce clairvoyantly picked up certain data about present conditions of the sitter (either psychically or from readily-available information), such data would be translated symbolically into a certain time-culture slot. A foreign birth was translated into a previous incarnation in that land. The symbolic understanding also explains why the fifteen time-culture slots concentrated on ones relatively well-known to the average American in the early twentieth century. Cayce was using those eras about which he had been taught by his public school education, church school, and the Theosophist Lammers. Thus American pioneers, the Crusaders, the fall of Troy, Old Testament times, Jesus’ era, mystic Egypt and occult Atlantis all appear. Even the Essene material is directly derivative of two occult best-sellers—The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ by Levi H. Dowling and The Mystical Life of Jesus by Rosicrucian author H. Spencer Lewis.

Seaside Interlude

After escaping the poverty of Dayton through the help of a new donor in 1925, Cayce relocated to Virginia Beach, a town selected by the readings. He basked in the ocean climate and nearby fishing. More importantly, he finally raised enough money to open his “Hospital of Enlightenment.”

In 1929, Cayce and supporters unveiled a thirty-bed facility on a small hill overlooking the Atlantic. It provided a comforting, homey setting that more resembled a shingled seaside inn than medical facility. But it was a real clinic. Amid sunshine, shuffleboard, and tennis, the hospital was staffed by MDs, nurses, osteopaths, and chiropractors.

Patients could receive clairvoyant diagnoses and alternative therapies such as massage and colonics, along with modern X-rays, urinalyses, and blood work. Cayce delivered a metaphysical lecture each Sunday. He made some of the first prescriptions of meditation as an emotional aid. The Cayce hospital was, perhaps, the fullest effort at that point in history to unify body-mind-spirit therapies.

In one of the signature tragedies of Cayce’s life, however, arguments with investors and arrival of the Great Depression closed the facility within two years. Attempts to open a metaphysical college, Atlantic University, ended similarly.

In winter 1931, Cayce came to feel that his life’s work had bottomed out. He watched patients leave and files and supplies get carted off. Alone, the seer wandered the halls ghostlike, gathering personal belongings before the building was boarded up.

“I’ve been tested,” Sugrue quoted him telling Gertrude. “And I’ve failed.”

Broken and withdrawn, Cayce retreated to solaces he knew as a boy: Bible-reading, gardening, fishing, and chopping wood. Although his frame sagged under disappointment, he carried on his clairvoyant readings at an intensive pace.

Months after the hospital’s closing, Hugh Lynn, then twenty-four, approached his father with an idea. As Hugh Lynn saw it, Edgar needed to break free from dependency on one or two big donors, as well as casual querents interested solely in personal readings.

Instead, Hugh Lynn envisioned a member-supported organization—one that possessed: 1) financial independence; 2) willingness to do as much, or as little, as its member-sustained budget permitted; and 3) ability to organize, verify, and cross-reference the readings so that patients and seekers were no longer treated in isolation.

At these aims, the emergent group, Association for Research and Enlightenment (A.R.E.), generally succeeded. Across years, it, too, suffered intermittent setbacks rooted in member factionalism and leadership misjudgments. Of this, no organization is free.

Documenting the Prophet

Cayce was, finally and fatefully, introduced to the world—and memorialized beyond his death—by a New England journalism student and future biographer. This was Thomas Sugrue (1907-1953).

When Sugrue met Cayce in 1927, the budding author was deeply versed in world affairs and determined to break into international reporting. Sugrue had left his native Connecticut in 1926 for Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, which was then one of the only schools offering a journalism degree. Sugrue later switched his major to English literature, in which he earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in four years.

As a student, Sugrue was not drawn to psychics or séance parlors. A devout Catholic who considered joining the priesthood, the aspiring reporter winced at talk of ESP or paranormalism. Yet Sugrue met a friend at Washington and Lee who challenged his preconceptions: the psychic’s eldest son, Hugh Lynn. Hugh Lynn had planned to attend Columbia but Edgar’s clairvoyant readings redirected him to the old-line Southern school.

Sugrue grew intrigued by his classmate’s stories about his father, in particular the elder Cayce’s theory that one person’s subconscious could communicate with another’s. The freshmen enjoyed sparring intellectually and soon became roommates. While cautious, Sugrue wanted to meet the agrarian seer.

Edgar and Gertrude, meanwhile, were laying new roots in Virginia Beach, about 250 miles east of Lexington. The psychic spent the remainder of his life in the coastal town, delivering twice-daily readings and, with Hugh Lynn, building A.R.E.

Accompanying Hugh Lynn home in June 1927, Sugrue received a “life reading.” Cayce correctly identified the young writer’s interest in the Middle East, a region from which Sugrue later reported on the founding of the modern state of Israel.

It was not until Christmas, however, that Sugrue, upon receiving an intimate and uncannily accurate medical reading, converted wholeheartedly to Cayce’s psychical insight. Although Sugrue fulfilled his dream of reporting internationally, including for The New York Herald Tribune and The American Magazine, his life remained bound to Cayce’s.

Stricken by debilitating inflammatory arthritis in the late 1930s—Sugrue believed it followed an infection contracted abroad—he sought recovery through Cayce’s work. From 1939 to 1941, the ailing Sugrue lived with the Cayces in Virginia Beach, writing and convalescing. During the period of close proximity, while struggling with painful joints and limited mobility, Sugrue completed There Is a River, the sole biography of Cayce written during his lifetime.

When the book appeared in 1942, it brought the psychic national notice that surpassed the earlier New York Times coverage.

“I’m the kind of man who believes in X-rays”

There Is a River pierced the skeptical wall of New York publishing due to a reputable editor, William Sloane, of Holt, Rinehart & Winston, who experienced his own brush with Cayce’s readings.

In 1940, Sloane agreed to consider the manuscript for There Is a River. He knew the biography was highly sympathetic, which did not endear him to it. Sloane’s wariness dissipated after Cayce’s clairvoyant diagnosis helped one of the editor’s children.

Novelist and screenwriter Nora Ephron recounted the episode on August 11, 1968, in The New York Times. “I read it,” Sloane told Ephron. “Now there isn’t any way to test a manuscript like this. So I did the only thing I could do.” He continued:

A member of my family, one of my children, had been in great and continuing pain. We’d been to all the doctors and dentists in the area and all the tests were negative and the pain was still there. I wrote Cayce, told him my child was in pain and would be at a certain place at such-and-such a time, and enclosed a check for $25. He wrote back that there was an infection in the jaw behind a particular tooth. So I took the child to the dentist and told him to pull the tooth. The dentist refused—he said his professional ethics prevented him from pulling sound teeth. Finally, I told him he would have to pull it. One tooth more or less didn’t matter, I said—I couldn’t live with the child in such pain. So he pulled the tooth and the infection was there and the pain went away. I was a little shook. I’m the kind of man who believes in X-rays. About this time, a member of my staff who thought I was nuts to get involved with this took even more precautions in writing to Cayce than I did, and he sent her back facts about her own body only she could have known. So I published Sugrue’s book.

Many historical writers since Sugrue have traced Cayce’s life. Journalist Sidney D. Kirkpatrick wrote the flagship record in his 2000 biography, Edgar Cayce. Historian K. Paul Johnson crafted a balanced and meticulous scholarly analysis in his 1998 Edgar Cayce in Context. Intrepid scholar of religion Harmon Bro, who spent nine months with Cayce toward the end of his life, produced insightful studies of the seer as a Christian mystic in his 1955 University of Chicago doctoral thesis—a groundbreaking work of modern scholarship on an occult subject—and later in his 1989 biography, Seer Out of Season.

I will always remember encountering Bro’s book at age twenty-two as an editorial assistant at New American Library: it marked my introduction to Cayce. While Bro died in 1997, his family has a long—and active—literary involvement with Cayce. Bro’s mother, Margueritte, was a pioneering female journalist in the first half of the twentieth century who also brought Cayce national attention in her 1943 profile in Coronet magazine: “Miracle Man of Virginia Beach.”

The Mature Cayce

In Cayce’s august years, the once-awkward, soft-voiced adolescent grew into a sought-after spiritual messenger who sought no one’s patronage or approbation. But the seer never quite knew how to manage fame—and, most especially, money. He often waived or deferred his usual $20 fee for readings, leaving his family in a perpetual state of uncertainty.

In a typical letter from 1940, Cayce told a blind laborer who asked about paying in installments: “You may take care of the [fee] any way convenient to your self—please know one is not prohibited from having a reading . . . because they haven’t money. If this information is of a divine source it can’t be sold, if it isn’t then it isn’t worth any thing.”

On a personal note, I have found inspiration in Cayce’s attitude, perhaps not always balancing matters soundly in finance and spirituality, but erring on the side of fairness and gratis activity when moved. I believe that practitioners of any type are due payment; but I signal caution around fee-for-service hourly arrangements—not because they are wrong ethically or empirically but because the search is, by nature, inexact. Most people who visit hourly psychics are, almost by definition, in emotional need. They want to believe in the oracular agency of the seer. This symmetry must be approached with care.

The mature Cayce remained a man of religious devotion struggling to reach terms with the occult subjects that populated his readings since the early 1920s. This material extended to numerology, astrology, crystal gazing, modern prophecies, reincarnation, karma, and mythical civilizations, including, of course, Atlantis and prehistoric Egypt.

People who sought readings were intrigued and emotionally impacted by such matters as much as Cayce’s medical diagnoses. Moreover, in readings covering esoteric topics—along with more familiar ones focused on holistic remedies, massage, meditation, and natural foods—there emerged a range of topics that formed the catalog of New-Age spirituality in the twentieth century.

But Cayce did more than sound reveille for the New Age. The spiritual thread connecting his readings, combined with his correlative study of Scripture, traced a universal approach to the traditional faiths.

In evaluating the provenance of his psychism, Cayce settled on the principle that his ideas, whatever their origin, had to square with Gospel ethics. He addressed this in a talk delivered in his waking state in Norfolk, Virginia, in February of 1933, just before turning fifty-six:

Many people ask me how I prevent undesirable influences entering into the work I do. In order to answer that question let me relate an experience I had as a child. When I was between eleven and twelve years of age I had read the Bible through three times. I have now read it fifty-six times. No doubt many people have read it more times than that, but I have tried to read it through once for each year of my life. Well, as a child I prayed that I might be able to do something for the other fellow, to aid others in understanding themselves, and especially to aid children in their ills. I had a vision one day which convinced me that my prayer had been heard and answered.

In his independent reading of Scripture, Cayce reinterpreted the ninth chapter of the Gospel of John, in which Christ heals a man who had been blind from birth, to validate karma and reincarnation. When disciples ask Christ whether it was the man’s sins or those of his parents that caused his affliction, the master replies enigmatically: “Neither hath this man sinned, nor his parents: but that the works of God should be made manifest in him.” (John 9:3)

In Cayce’s reasoning, since the blind man was born with his disorder, and Christ exonerates both sufferer and parents, his disability must be karmic baggage from a previous incarnation. Cayce made comparable interpretations of passages from Matthew and Revelation.

Seer’s Reach

Cayce did not live long enough to witness the full reach of his influence. The psychic died at age sixty-seven in Virginia Beach at the start of 1945, less than three years after There Is a River appeared. Sugrue updated the book that year. After struggling with years of illness, the biographer died at age forty-five on January 6, 1953, at the Hospital for Joint Diseases in New York.

The first popularizations of Cayce’s work began to appear in 1950 with publication of Many Mansions, a work on reincarnation and karma by Gina Cerminara, a Cayce devotee. It was not until 1956, however, that Cayce’s name again soared through the mass bestseller The Search for Bridey Murphy by Morey Bernstein. Sugrue’s editor Sloane, having since warmed to parapsychology, published both authors.

Bernstein was an iconic figure. A Coloradan of Jewish descent and an Ivy-educated dealer in heavy machinery and scrap metal, he grew inspired by Cayce’s career and became an amateur hypnotist. In the early 1950s, Bernstein conducted a series of experiments with a Pueblo, Colorado, housewife who, when put under, appeared to regress to a past-life persona: an early nineteenth-century Irish girl, Bridey Murphy. The entranced homemaker spoke in an Irish brogue and recounted comprehensive details of her rural life from over a century earlier.

Suddenly, reincarnation—an ancient Vedic concept about which Americans had heard little before World War II—was the latest craze, ignited by Bernstein, an avowed admirer of Cayce, to whom the hypnotist devoted two chapters. In 1956, Life magazine wrote of past-life costume soirees called Come as You Were parties. A popular joke made the rounds: Did you hear the one about the man who read Bridey Murphy and changed his will? He left everything to himself.

Also that decade, Beat muse Neal Cassady introduced the Cayce readings to his literary circle, including Jack Kerouac—who was having none of it. In 1992, poet Allen Ginsberg recalled in Tricycle:

Jack Kerouac’s interest in Buddhism began after he spent some time with Neal Cassady, who had taken on an interest in the local California variety of New Age spiritualism, particularly the work of Edgar Cayce. Kerouac mocked Cassady as a sort of homemade American ‘Billy Sunday with a suit’ for praising Cayce, who went into trance states of sleep and then read what were called the Akashic records, and gave medical advice to the petitioners who came to ask him questions with answers which involve reincarnation.

As memories of the fifties faded, Cayce’s name rose Phoenix-like in California journalist Jess Stearn’s 1967 bestseller, Edgar Cayce, The Sleeping Prophet. With the mystic sixties in full swing and the youth culture embracing all forms of alternative or Eastern spirituality—from Zen to yoga to psychedelics—Cayce, while not explicitly tied to any of this, rode the new vogue.

During this period, Hugh Lynn emerged as a formidable custodian of his father’s legacy, shepherding to market a new wave of instructional guides based on Cayce’s teachings, from dream interpretation to drug-free methods of relaxation to spiritual uses of colors, crystals, and numbers. Thereafter, Cayce remained fixed on the cultural landscape.

The sixties and seventies also saw a new generation of channeled literature from beings such as Seth, Ramtha, and even the figure of Christ in A Course in Miracles. The last of these was a profound and enduring lesson series, channeled beginning in 1965 by Columbia University research psychologist Helen Schucman.

A concordance of tone and values connected Cayce and A Course in Miracles. Readers of both blended seamlessly, attending many of the same seminars, growth centers, and metaphysical churches.

Likewise, congruency appeared between Cayce and the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous. Starting in the 1970s, Twelve-Steppers of various stripes became a familiar presence at Cayce conferences and events. Cayce’s universalistic religious message dovetailed with purposefully porous references to a Higher Power in the “Big Book,” Alcoholics Anonymous, written in 1939.

AA cofounder Bill Wilson, his wife and intellectual partner Lois, confidant Bob Smith, and several early AAs were deeply versed in mystical and mediumistic teachings.

In recently unearthed correspondence, Bill wrote to Hugh Lynn Cayce, on November 14, 1951: “Long an admirer of your father’s work, I’m glad to report that a number of my A.A. friends in this area [New York City], and doubtless in others, share this interest.”

Bill commented revealingly on contacts that Hugh Lynn had proposed between the Cayce world and AA:

As you might guess, we have seen much of phenomenalism in A.A., also an occasional physical healing. But nothing, of course, in healing on the scale your father practiced it . . . At the present time, I find I cannot participate very actively myself. The Society of Alcoholics Anonymous regards me as their symbol. Hence it is imperative that I show no partiality whatever toward any particular religious point of view—let alone physic [sic] matters. Nevertheless I think I well understand the significance of Edgar Cayce and I shall look forward to presently hearing how some of my friends may make a closer contact.

All three works—the Cayce readings, A Course in Miracles, and Alcoholics Anonymous—displayed a shared sense of religious liberalism, encouragement to seek one’s own conception of a Higher Power, and flexibility in spiritual outlook. The free-flowing culture of the therapeutic-spiritual movements of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries had convergence, if not direct ancestry, in the Cayce readings.

It must be added, however, that this culture had parameters. Striped of dramatic overlays, whether in the form of akashic records, UFOs, channeling, or Ascended Masters, the New Age often assumed a monotheistic, sin-and-salvation, sometimes-popularized karmic system. Whatever its liberality toward Abrahamic, Vedic, and Buddhist expressions, New Age culture generally wove a garment of, not quite traditionalism—evangelicals scorned the New Age as heretical and cynics dismissed it as “cafeteria religion”—but rather an inverted Biblical injunction: old wine in new bottles. The dawning culture sought less to question existing models than foster novel entries to them.

As I write these words, an us-vs-them conspiracism is increasingly heard—though still very much in the minority—within the New Age. This results, in part, from suspicions toward conventional medicine and other institutions considered stifling of human potential and concealing of greater truth. This phenomenon, a kind of lumpen gnosticism, invests less in freeing self than identifying enemies. It has, in my reading, no antecedent in Cayce.

What Remains

Writing in 2025, more than a century since Cayce’s public emergence, provides opportunity for perspective. I see Cayce as modernity’s most effective and personally appealing spiritual synthesizer. His ecumenism, innovation, practicality, and popular framing gave searching people myriad doorways to query and effort, which are, finally, evaluable only by individual experience.

There exist limits to the Cayce outlook, which draws on homiletic shades of the King James Bible, and onto which seekers, given the sprawling and sometimes abstruse nature of the readings, are apt to project their own predilections. Within the Cayce fold appear perils—intrinsic to any codified legacy—of institutional boundaries and sectarianism; this has, as I write these words, muffled the subculture’s once-vibrant intellectual exchange. I first attended A.R.E. in the company of philosopher Jacob Needleman (1934-2022) and scholar of religion Mark Thurston. My own heresies have since rendered me unwelcome. One staffer privately wrote, “They may erase you from the website but they cannot erase you from our hearts.” That is the Cayce I know.

I consider Cayce’s psychical abilities genuine. I likewise consider such capacities, by nature, conditional and, hence, uneven, something Cayce himself conceded. One cannot apply a standard of constancy to his readings or, I believe, to any. On that scale, the seer, like the seeker, must be weighed in conduct. By such measure, Cayce can only be deemed a worthy messenger.

"I first attended A.R.E. in the company of philosopher Jacob Needleman (1934-2022) and scholar of religion Mark Thurston. My own heresies have since rendered me unwelcome."

Any space that cannot bear heresies doesn't deserve them. I think Cayce did good work... as do you.

Great piece of writing, had to look up a few words and concepts along the way, always a good sign..

Thank you 🙏