At a time of national division, one may wonder what this year’s Fourth of July holiday stands for. I take this moment to explore occult scholar Manly P. Hall’s (1901-1990) vision of the United States. Hall’s point of view, steeped in both history and myth, frames the nation as a vessel for the individual search for meaning. Hall’s outlook does not easily fold into familiar political categories. In 2020, a writer in The New Republic—a university writing instructor no less—clipped and pasted (sans credit) my historical work on “Manley” P. Hall to construe him as the connecting joint of mysticism and rightwing politics, a point I never made. Since 2010, I have, however, unearthed connections between Hall and Ronald Reagan. [1] Since a not-quite-classifiable figure like Hall is easily misunderstood, I offer this article to contextualize the esoteric icon’s vision of American purpose on the eve our fitful national anniversary. -M-

________________

It can be argued that myth surpasses history. Myth captures the folds and failures, ideals and setbacks, behind history. Events pass; human nature, with its commonplace flaws and rare ideals, remains constant.

It is largely, but not wholly, in that vein that I approach the historical writing of modernity’s dean of occult letters Manly P. Hall: as amalgam of myth and event. And, ultimately, as a record of principles, which, too, are a function of myth.

The lowest reading of Hall’s work seeks a politics in it. There is none, at least not in the factionalist forms to which we are accustomed. Hall’s writing is idealistic but not prescriptive. His vision of America comports loosely with the outlook of a figure he venerated, Madame H.P. Blavatsky (1831–1891). In her 1888 opus The Secret Doctrine, the Russian occultist framed America, her adopted nation, as a vessel for preserving the individual search for meaning and related principles of expression and assembly. For these reasons, Blavatsky said in interviews and letters, she decamped to New York City in 1873, departing five years later for India as a U.S. citizen, a point of pride until her death.

Blavatsky’s description of America, and Hall’s seconding of it, would elicit only eyerolls and aha! cries of sanitized history (and worse) in most precincts of mainstream letters. Indeed, Hall’s two key works on the topic, The Secret Destiny of America (1944) and America’s Assignment with Destiny (1951), make only passing references to slavery. Of pre-Columbus America, Hall writes myopically in his earlier book, “Here was a virgin continent populated only by nomadic Indian tribes, a vast territory suitable in every way for the great human experiment of the democratic commonwealth.”

Hall ultimately ameliorates that statement with fuller treatment of Indian tribes of the Americas, both in these volumes and related articles. [2] Although these books were published seven years apart—The Secret Destiny of America began still earlier as a 1942 lecture and same-titled essay the next year—they work in tandem. America’s Assignment with Destiny fills out the first book with far greater exploration of the mythical and spiritual vision of Mesoamerican culture.

That said, Hall seems ill-at-ease surveying historical pillars that stand askew from his thesis, which is that the colonies functioned as inheritors of a “Universal Plan” preserved for centuries within teachings of esoteric fraternities and thought movements to one day blossom in a system of self-governance. He dates this “Order of the Quest” most fancifully to the pharaonic era up through initiatory orders of Hellenic antiquity and finally to modern philosophical upcroppings such as Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry.

Hall writes in The Secret Destiny of America:

Years of research among the records of olden peoples available in libraries, museums, and shrines of ancient cultures, has convinced me that there exists in the world today, and has existed for thousands of years, a body of enlightened humans united in what might be termed, an Order of the Quest. It is composed of those whose intellectual and spiritual perceptions have revealed to them that civilization has a Secret Destiny—secret, I say, because this high purpose is not realized by the many; the great masses of peoples still live along without any knowledge whatsoever that they are part of a Universal Motion in time and space.

In this article, I explore areas of Hall’s historical writing—which stands distinct from his virtuosic curation of symbology—in which he sometimes captures important and unseen currents of history; at other times, in an apparent overreach for philosophical symbiosis, he rushes into fanciful, under-sourced drama or interpretive leap. These approaches sometimes intermingle. In such cases, I attempt to augment the record with recent findings.

Inner America

Given what I have just written, why should the historically curious read Hall’s volumes on America? Despite his overconfidence in the motives of great men, Hall grasped the historic function of so-called secret societies, such as the Illuminati, founded as an effort of covert Jeffersonianism in monarchical Bavaria in 1776 and today clung to as a hidden League of Bad Guys among lumpen conspiracists.

As I explore in my 2023 Modern Occultism, the post-ancient model of spiritually based secret societies emerged from the backlash against occult experimentation of the Renaissance and curbing of religious freedom following the death of Elizabeth I. Historically, most denizens of esoterica and secrecy were not cloaked villains but self-preserving seekers and classically liberal intellects. As Hall astutely notes in Secret Destiny:

Secret societies have had concealment and protection as the first purpose for their existence. The members of these orders were party to some special knowledge, they usually took part in certain rites and rituals not available to nonmembers, but it was more important that through the societies they were also able to practice beliefs and doctrines in private for which they would have been condemned and persecuted if these rites were made public.

In this vein, Hall stands among the few historical writers who at least recognized the inceptive role of Freemasonry in America’s founding, a perspective only recently granted overdue treatment in scholarly literature. The founders included many Masons, such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Paul Revere, and John Paul Jones. Among signers of the Declaration of Independence, nine out of fifty-six were Masons, as were thirteen out of thirty-nine signers of the Constitution, and thirty-three out of seventy-four of Washington’s generals. (These figures do not match Hall’s in America’s Assignment with Destiny but are derived from standard record-keeping within contemporary Masonry.)

Freemasonry grew roughly parallel to the radically ecumenical and esoteric thought movement called Rosicrucianism, as well as the fading but persistent occult experimentation of the Renaissance. Following on the Grand Lodge of England in 1717, the first Masonic lodge in the American colonies appeared in 1731 in Philadelphia. (This date is based on lodge minutes. Since informality occasionally prevailed among nascent colonial lodges, the start date is sometimes set a year or more earlier while other lodges, including in Massachusetts and Virginia, claim precedence.) It bears noting that in America’s Assignment with Destiny, Hall is particularly strong exploring Masonic ties among early Latin-American liberationists, including Simón Bolívar (1783–1830) and Miguel Hidalgo (1753–1811).

Fraternal affiliation with an esoteric society was significantly defining of members’ lives in the American colonies. For generations following the Philadelphia lodge, and well into the nineteenth century, the nation remained a largely rural environment. Dominant institutions were farms, granges, trading posts, forts, armories, taverns, ports, and churches. There existed few venues to procure books, exchange ideas, and study the arts, sciences, or medicine (perhaps the one area where the colonies and new nation lagged behind Europe). Church life was dominant and notions of heresy very much alive.

Hence, to join Freemasonry meant undertaking a singular social bond. It was all-the-more remarkable to join a fraternal order that used occult, alchemical, and esoteric symbols as keys for ethical development, including the skull and crossbones, obelisk, all-seeing eye, serpent, ladder of wisdom, square and compass, Masonic letter G (of unknown provenance), and pyramid—symbols that populated the ancient religious imagination and were reconfigured, along with passion plays and initiatory rites, within Masonry.

Freemasonry recognized the basic validity of all faiths, including pre-Christian religions. I cannot overemphasize how radical a break that was with the mores of the Old World. The basic bylaws and documents of Freemasonry, even in the colonial era, while extolling primacy of a Creator, stopped short of elevating Christianity as the sole means of salvation. This indirectly validated occult philosophy.

The religious neutrality codified in the Declaration and Constitution grew from the Enlightenment philosophies of Locke, Voltaire, and Rousseau. But how many rural Americans read them? How many have today? Colonials, at least those of means, had the capacity to participate in a fraternal order that enshrined and protected the individual spiritual search—and believed that the search belong to no single congregation, doctrine, or dogma. That was the radicalism of Freemasonry. That is also why Masonry has historically been considered threatening to established religious authority.

In 1738, Pope Clement XII issued a papal bull—the most solemn form of announcement—against Freemasonry. The edict prohibited church members from participating in Masonry (there are many Catholic Masons today) and named it a heretical order antithetical to the church. Several reaffirming bulls and encyclicals appeared in future generations.

New Order of the Ages

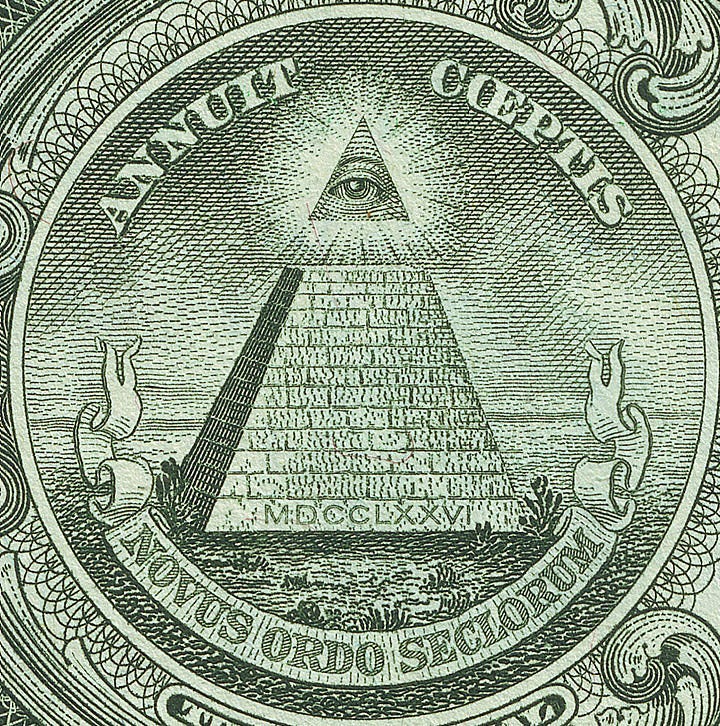

On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress formed a subcommittee chaired by Benjamin Franklin charged with designing the Great Seal of the newly declared nation. The Great Seal, ratified in 1782, displays on its front the familiar American eagle grasping olive branches in its right talon and arrows in its left. But the reverse of the Great Seal conveys a more esoteric meaning. It appears today on the back of the U.S. dollar bill, where it was not actually placed until 1935—by, as it happens, two twentieth-century Masons: Secretary of Agriculture (and later Vice President) Henry A. Wallace and President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The image shows the pyramid and all-seeing eye or, classically, Eye of Horus, hovering above it. The incomplete pyramid is capped by the eye of providence to suggest that material achievement is incomplete without higher understanding or gnosis. Surrounding it is the Latin maxim, Annuit Coeptis Novus Ordo Seclorum, roughly translated, Providence Smiles on Our New Order of the Ages. It is not a Masonic symbol. But I think it fair to venture that it is inspired by Freemasonry, whose lexicon included the all-seeing eye. The symbolism is Masonic philosophy defined: earthly works are incomplete without the light of wisdom.

As the more idealistic founders saw it, the new nation was part of a revived chain of great civilizations, including Egypt, Greece, Persia, and Rome, which saw their purpose intertwined with the ageless wisdom and will of destiny. This is also reflected in the Hellenic-Egyptian architecture that came to characterize the U.S. capital.

Before moving on, I want to note a strand of Freemasonry that is important to American history but poorly understood and absent from Hall’s purview. That is Prince Hall Masonry, a Black Masonic order. In the 1770s, a freed man of color named Prince Hall (c. 1735/8–1807), who was a Boston leatherworker, assembled with fourteen Black colleagues to form a Freemasonic lodge. Refused entry to mainline Masonry, the men organized into African Lodge №1.

The historicism of Prince Hall Masonry has, until recently, been marred by mistakes stemming from documents of the late-eighteenth century. Much of traditional history records that Prince Hall Masonry was founded in 1775. It was not. That error got inserted into records of the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1795 and was thereafter widely repeated. Hence, even materials of significant vintage and familiar sourcing require checking. Two impeccable Masonic historians, John L. Hairston Bey and Oscar Alleyne, produced a clarifying monograph in 2016, Landmarks of Our Fathers. Revisiting original records, the authors determined that the founding of Prince Hall Masonry, or African Lodge №1, was not 1775 but 1778.

Prince Hall served as the lodge’s first Grand Master and his branch of Freemasonry later took his name as an extant Black Masonic movement. Prince Hall Masonry is today increasingly recognized within traditional Masonry. Importantly, Prince Hall’s name appeared on two petitions opposing slavery in the American colonies: one in 1777 and one in 1778, the founding year of African Lodge №1. These are among the earliest anti-slavery petitions in the colonies. In effect, the first Black-led abolitionist movement in America was Freemasonic. I am not saying that abolitionism arose from Freemasonry. Abolitionism had many thought-streams, including Quakerism. But with discovery of Prince Hall’s signature on these early petitions, and understanding when Prince Hall Masonry was founded, the confluence is important to note.

Fantasy Pharaoh

In reckoning with pharaonic history—the opening leaf of his “Order of the Quest”—Hall displays weakness. The second chapter of The Secret Destiny of America, titled “The World’s First Democrat,” presents a hagiographic biography of Pharoah Akhenaten (reigning c. 1353–1336 or 1351–1334 B.C.) as an enlightened pre-modern populist and seeker-king.

Hall’s account appears largely based on the 1930 record of Akhenaten in Charles F. Potter’s The Story of Religion, as well as early twentieth-century romanticization of the little-understood ruler, who evoked fascination in the wake of fin de siècle excavations that uncovered the pharaoh’s ceremonial center and capital at Amarna. [3]

A controversial figure who often polarizes historians, Akhenaten and queen Nefertiti instituted an exclusive, nationwide religion of sun worship, or Atenism, throughout the ancient empire. Seen by some, including Sigmund Freud (who considered Moses himself a priest of Akhenaten in his 1939 Moses and Monotheism published the year of his death), this reform marked the dawn of monotheism.

Seen by others, Atenism represented a forcible schism and state-instituted faith, quickly forsaken after the leader’s death by a public and ruling class eager to resume polytheism. Indeed, soon after the pharaoh died, courtiers and ministers abandoned his center of Amarna, built in honor of the mono-deity Aten. Akhenaten’s eventual successor and likely son, Tutankhamen, ruled in Luxor with full restoration of Egypt’s pantheon.

Lost Continent?

Several times in both books on America, Hall references Atlantis. Given the controversial nature of such references, the topic requires unpacking from a contemporary perspective. Was Atlantis real? Does history conceal a lost culture whose rise and fall proffers crucial, even existential, questions for humanity?

Across his career, Hall wrote with historical interest about the theorized continent of Atlantis, drawing upon myriad sources, including, of course, the Platonic dialogues Critias and Timaeus. Plato’s speakers, particularly those for whom the dialogues are named, describe a vanished, advanced civilization in the Atlantic. Their testimony draws upon recollections of legendary Athenian statesman, Solon (c. 630–c. 560 B.C,), who was said to have visited Ancient Egypt where priests taught him humanity’s primeval origins. Plato’s record says that the seafaring empire grew so powerful that hubris led it to the ultimate trespass: attacking Athens itself. The Athenians repelled the attack, ushering in the fall and disappearance of this once-upon-a-time civilization.

Because Hall uses contemporaneous historical sources to consider the historicity of Atlantis, it is important, I think, to note something about the question from the perspective of the late-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Through the work of a wide range of popular figures, including English theorist John Michell (1933–2009) and author-investigator Graham Hancock (b. 1950), our era has experienced renewed interest in questions of lost, remote, or Atlantean civilizations, a theme also appearing in the work of nineteenth and twentieth-century mystics Blavatsky, G.I. Gurdjieff (c. 1866–1949), and Edgar Cayce (1877–1945), among others.

In 1961—in what proved a fateful remark toward the end of his life—esoteric Egyptologist R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz (1887–1961) wrote that the “Sphinx whose leonine body, except for the head, shows indisputable signs of aquatic erosion,” as translated in 1982 in his Sacred Science. The actuality of water erosion on the oldest portions of the monument could predate its timeline and, hence, that of Ancient Egypt, suggesting the existence of a prehistoric civilization.

Ignited by Schwaller’s comment, independent Egyptologist John Anthony West (1932–2018) extrapolated on the water-erosion thesis in his 1979 book Serpent in the Sky. About a decade later, West partnered with Yale-trained geologist Robert M. Schoch to investigate the theory on a 1990 archeological expedition to Egypt. The following year, Schoch presented the water-erosion thesis, positing that water damage detected on the earliest portions of the Sphinx would predate the dawn of Egyptian civilization to 7,500 B.C. or as early as 10,000 B.C.

In a coup of esoteric philosophy, the Schoch-West thesis formed the basis of an Emmy-winning and widely viewed 1993 network TV special, “Mystery of the Sphinx,” hosted by Charlton Heston. The stage was set for mainstream consideration. But West, a mercurial man, never completed work on a book exploring the water-erosion thesis. When I got to know West in the years before his 2009 death, I pushed the brilliant but erratic author-investigator, unsuccessfully, to resume that work.

Today, academic archeologists (or at least those vocal on the matter) vociferously dispute the Schoch-West thesis. No archeologist, however, has directly contradicted it; i.e., no one has performed investigatory work on the monument that dispels the Schoch-West profiling. The most compelling (and oft-heard) argument cites absence of a shard of pottery or piece of material evidence that corroborates the Schoch-West timeline.

I brought this to the attention of West when he was living not far from me in the Hudson Valley region of New York. His counter was that further investigation is required; he and Schoch, he argued, pinpointed a vital piece of empirical evidence, which no one in the field has directly upended. There exist contradictory theories, of course, which also reference environmental and quarrying factors. These counter-theories, in my view, raise important points but remain tangential to the Schoch-West findings.

Observers may wonder: where is the rising generation of professors, grad students, and archeologists who want to review the Schoch-West research and directly check the evidence? This poses questions about the politics of academia and archaeology in our era.

First, it is extremely difficult to gain exploratory access to the Giza Plateau. Licensure is tightly regulated and costly. Moreover, getting “green lit” for such a study from most Western universities is nearly impossible. Schoch, who is on the faculty of the College of General Studies at Boston University, argued to me that if a graduate student or anyone in the field of archaeology expresses interest in exploring the water-erosion thesis, it is career suicide. Most academics disdain the Schoch-West data because it indirectly undermines the timeline on which many have based their work. They would, of course, argue that they disdain it because it is pseudoscience, a disabling label that, in my estimation, requires the same level of evidence as its object. Science is methodological replication. If you have not located flaws in methodology then you are arguing taste. In any case, the timeline is considered settled—and if anyone raises questions adjacent to it, that person is regarded as implicitly challenging the research on which many figures in the field built their reputations. Hence, licensing, funding, and approbation are absent.

There exists a geopolitical barrier, as well. Modern Egypt justly prides itself as the cradle of civilization. To some degree, this perception plays a nationalistic role in Egyptian life, as does custodianship of antiquities in many nations. Some government officials believe that any attempt to predate the timeline of Ancient Egypt strikes at the heart of the nation’s heritage. I suggest a different framing. If research posits that Egypt possesses deeper antiquity than the accepted timeline that prospect only enriches and fortifies the civilization’s vintage. Many Egyptian officials see it differently. (Their wariness is exacerbated by the ancient-alien thesis, a topic unconnected to the Schoch-West report.)

In his magisterial 1950 allegory Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson, spiritual philosopher G.I. Gurdjieff wrote of the existence of a remote civilization, which bears the same timeline as the Schoch-West thesis.

The Schoch-West thesis also comports with the timeline that Manly P. Hall posits. It likewise meshes with some of what Plato recorded in his dialogues. So, I believe there exists a tantalizing question—one left largely unaddressed in our era. There are, to be sure, explorers who fund independent missions to different parts of the world—coastal waters off Turkey, the Caribbean, the Mediterranean—some of whom have cited evidence of untracked civilizations whose ruins they believe lie beneath the ocean’s tides. These claims remain controversial.

Native Culture

At points, The Secret Destiny of America makes ancient Mesoamerica sound like an unspoiled version of mythical Atlantis:

The Mayas were hospitable, kindly, gentle, and industrious; their cities were beautiful in every way; they were public spirited, well governed, and according to the order of their time, highly educated. The religious temper of the people can be gathered from remnants that still survive. It is common to all the Indians of the Americas that religious intolerance is utterly beyond their comprehension. They look upon each man’s religion as his own particular belief, and if it suits his needs it deserves the respect of all other rightminded men. Thus we see that the archetype for a generous and enlightened way of life is part of the American continent’s common inheritance.

I must again note that Hall’s treatment of pre-Columbian religion and symbolism is far fuller in America’s Assignment with Destiny, which I consider the stronger, if less influential, of the two books. But in no case can Mayan civilization be framed as one continuous whole. Throughout its so-called classical period from about 250 A.D. to 900 A.D., Mayan society experienced myriad change and permutation. There existed periods of relative peace, periods of warfare, periods in which certain understandings and styles of building were in demand, were practiced, and then receded, to be replaced by other styles. All this grew from both social necessity and ideas that ancient people held about themselves.

Mayan civilization relates, at least in a memetic sense, to the Atlantean thesis. As noted, there existed stages of profound violence and warfare during various epochs of Mayan civilization as well as within those civilizations, such as the Aztecs, that branched off from the Maya. Aztec culture, which flourished from about 1300 to 1521, saw periods of public execution, human sacrifice, and ritualized violence. Such activities, when they occurred, tended to fall in latter stages of these civilizations.

Students of history have asked why Mayan and Aztec culture at times codified ritual violence and brutality. Ptolemy Tompkins, a thoughtful writer of esotericism, has broached a penetrating theory. Ptolemy traveled extensively in Central America and his father, Peter Tompkins (1919-2007), was an independent archeologist, in the mode of John Anthony West. Noting that latter-day Mayan and Aztec civilizations engaged in blood sport and sometimes blood sacrifice, he theorized that in earlier stages these civilizations felt more possessed of a vital understanding of the interconnectedness of all things—they felt close to the gods or the cosmos. Their knowledge and understanding of nature harbored real profundity. But in later stages, it may be that some of these insights grew lost within both the culture and individual. When feelings of vitality and connectedness get lost, people often seek alternate ways of heightening a sense of thrill and purpose, such as in drugs, foolish thrills, anger—and sometimes violence.

Violence or its witnessing can give the individual a false feeling of life. This was true of the murdering of martyrs, for example, in the Colosseum at Rome. Some apparently universal fissure in human nature attracts us to bloodshed or its imitation, which provides a perverted sense of vitality. Vernon Howard (1918–1992), a brilliant modern mystic, spoke of the “false feeling of life” that often accompanies hostility, anger, violent entertainment, and acts of both physical and emotional violence, including attacking people on social media.

Hence, Ptolemy theorized that some of the Mesoamerican civilizations in their latter stages may have devolved into ritualized violence, which one could also say about our own civilization. The ancients lost connection as cultures and as individuals with the first principles of life. And, feeling bereft of those vital first principles and their vivifying qualities, they resorted to violence for a false thrill—for the rush one gets when feeling that all possibilities are open, all barriers have fallen, all paths extend before you. It proved a harbinger of the fall of some of these great civilizations.

Hermetic America

Hall sometimes over-relied on folkloric or single sources with some legend mixed in. This includes his writing about influential German-American Pietist and mystic Johannes Kelpius (1667–1708). But Hall must also be applauded for writing about Kelpius at all in an era when historians overwhelmingly ignored the Hermetic monk who formed an important link in the colonies’ reputation as a home for religious radicals.

The mystic Kelpius and his circle of followers (legend says forty) fled religious persecution and fears of apocalypse in Central Europe in 1693, reaching the colonies the following year to establish a monastic hermitage in Philadelphia, then a cluster of several hundred houses, on the banks of the Wissahickon Creek just outside town. The rustic commune helped establish the colonies as a safe harbor for Old World heresies. As news traveled, other experimenters, including Conrad Beissel (1691–1768) who founded a more-lasting religious colony at Ephrata, Pennsylvania, followed Kelpius’s footsteps.

Hall discounts claims that the Kelpius circle harbored Rosicrucian philosophy or ties. While the history remains oblique, it should be noted that Pietism—a mystical movement within the Lutheran church—is today increasingly considered the source of at least some of the first Rosicrucian manuscripts that began circulating in Central Europe in the early 1600s. [4]

In any case, the monk’s influence is seminal—and increasingly recognized as such by historians of religion. In 2024, Oxford University Press published the first scholarly biography of Kelpius, American Aurora: Environment and Apocalypse in the Life of Johannes Kelpius by Timothy Grieve-Carlson. (My review appears here.)

Although Hall, writing in America’s Assignment with Destiny, proffers fanciful episodes from the pilgrim’s life, involving secret caskets and alchemical explosions, his work kept this important figure from being written out of religious and American history at the time. Today, no account of the development of the nation’s religious culture is complete without at least noting him.

Mystic-In-Chief

We finally reach one of Hall’s most pronounced if little-seen impacts as a historical writer: his work ignited the patriotic imagination of a budding political aspirant and Los Angeles contemporary, Ronald Reagan (1911–2004).

I discovered in 2010 that some of Hall’s ideas and language about the inner meaning of America began appearing in Reagan’s writing and speechmaking from the earliest years of his political career up through the second-term of his presidency. As we soon see, it is likely the two met in their hometown of LA while Reagan was California’s governor. In this sense, Hall’s influence travelled beyond esoteric circles. The most powerful example appears in his impact on one of the twentieth-century’s most consequential politicians.

During Reagan’s two terms as governor, from 1967 to 1975, whispers and speculation circulated about the ex-actor’s penchant for lucky numbers, superstition, and newspaper horoscopes. But it was unknown that esoteric scholar Hall, and particularly his occult backstory of America, made a lasting impact on the man who became fortieth president.

Typical of many actors, Reagan was no stranger to occult lore. As explored in my Occult America, he was friendly with Eden Gray, a onetime costar who went on to write the nation’s first popular guides to Tarot. Later as governor, Reagan was friends with psychic Jeane Dixon (he and Nancy broke with the prophetess after she failed to foresee his rise to the White House), and, as noted in his 1965 memoir, Where’s the Rest of Me?, was “good friends” with Santa Monica stargazer Carroll Righter, who in 1969 became the first, and only, astrologer to appear on the cover of Time magazine.

Deep into the second term of Reagan’s presidency in the spring of 1988, stories about Ronald and Nancy Reagan’s interest in the occult broke into full view. A tell-all memoir by disgruntled ex-chief of staff Donald Regan definitively linked Nancy to San Francisco astrologer Joan Quigley (1927–2014), who closely monitored the president’s calendar and appointments.

Speaking at a press briefing, White House spokesman Marlin Fitzwater attempted to quickly dispel the matter by acknowledging that, yes, the Reagans are fans of astrology, but never use it for policy decisions; the spokesman also conceded the president’s penchant for “lucky numbers” or numerology. To many political observers, the revelations cemented press speculations that arose when Reagan, as governor-elect, scheduled his first oath of office at the eyebrow-raising hour of 12:10 a.m., which critics saw as an effort to align the inaugural with promising heavenly signs.

During his 1980 presidential campaign, Reagan sat for a three-hour interview with journalist Angela Fox Dunn, daughter of Malvina Fox Dunn, Reagan's drama coach at Warner Brothers in the 1930s. Reagan never opened up so much as when he was around people with ties to his movie days. With surprising frankness, the Republican nominee expounded on topics ranging from the astrological signs of past presidents, to his mother's religious beliefs, to the prophetic qualities of psychic Jeane Dixon, another old Hollywood friend.

While Dixon was "always gung-ho for me to be president," Reagan related, in the "foretelling part of her mind" the prophetess didn't see him in the Oval Office. (A prediction that, more or less, squared with Dixon’s record.) He also boasted to Dunn of being an Aquarius, the most mystical of all the zodiac signs. “I believe you'll find that 80 percent of the people in New York's Hall of Fame are Aquarians,” he said. (It is not clear what Hall of Fame Reagan was referencing—it may have been the Hall of Fame for Great Americans at New York's Bronx Community College. If so, he would have been disappointed to learn that Aquarians are not overrepresented among its inventors, statesmen, and scientists.)

But a bigger and more substantive piece of the story went missing. In speeches and essays produced decades apart, Reagan revealed the unmistakable mark of Hall’s writing and phraseology. Judging from a tale of Hall’s that Reagan borrowed and often repeated, the president’s interests in the esoteric extended far beyond daily horoscopes.

“Unknown Speaker”

As noted, The Secret Destiny of America describes how the nation emerged from a “Great Plan” for religious liberty and self-governance launched by ancient philosophers and secret societies. Hall located these principles within Western esoteric traditions. He believed such aims were codified within the work of illumined modern intellects, such as Francis Bacon and Sir Walter Raleigh, as well as covert fraternities, including Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism (the latter probably not an actual brotherhood but a thought movement) and eventually enacted by America’s founders, many of whom were, as noted, either Masons or steeped in ethical and individualist philosophy, such as Paine and Jefferson.

In Hall’s original 1943 essay and 1944 book, he recounts a rousing speech delivered by a mysterious “unknown speaker” before signers of the Declaration of Independence. Hall also told an earlier version of this story in his 1928 opus, The Secret Teachings of All Ages.

“This strange man, who seemed to speak with a divine authority,” Hall wrote in Secret Destiny, invisibly entered and exited the locked doors of the Philadelphia statehouse on July 4, 1776, delivering an oration that bolstered the wavering spirits of delegates.

“God has given America to be free!” commanded the stranger, urging delegates to overcome their fears of the noose, axe, or gibbet, and to seal destiny by signing the great document. Newly emboldened, Hall wrote, the listeners rushed forward to add their names. They looked to thank the speaker only to discover that he had vanished from the locked room. Was this, he wondered, “one of the agents of the secret Order, guarding and directing the destiny of America?”

At a 1957 commencement address in Illinois at his alma mater Eureka College, Reagan, then a corporate spokesman for General Electric, sought to inspire students with this leaf from occult history. “This is a land of destiny,” Reagan said, “and our forefathers found their way here by some Divine system of selective service gathered here to fulfill a mission to advance man a further step in his climb from the swamps.” Reagan then retold, without attribution, the tale of Hall’s unknown speaker. “When they turned to thank the speaker for his timely words,” Reagan concluded, “he couldn’t be found and to this day no one knows who he was or how he entered or left the guarded room.”

Reagan revived the story several times, including in 1981 when Parade magazine asked the new president for a personal essay on what Independence Day means to him. Longtime aide Michael Deaver delivered the piece with a note saying, “This Fourth of July message is the president’s own words and written initially in the president’s hand,” on a yellow pad at Camp David. Reagan retold the legend of the unknown speaker—this time using language very close to Hall’s own: “When they turned to thank him for his timely oratory, he was not to be found, nor could any be found who knew who he was or how he had come in or gone out through the locked and guarded doors.”

Continuing on Hall’s theme, Reagan spoke of America’s divine purpose and of a mysterious plan—this was Hall’s Order of the Quest—behind the nation’s founding. “You can call it mysticism if you want to,” he told the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in Washington, D.C., in 1974, “but I have always believed that there was some divine plan that placed this great continent between two oceans to be sought out by those who were possessed of an abiding love of freedom and a special kind of courage.” Reagan repeated these words almost verbatim before a television audience of millions for the Statue of Liberty centenary on July 4, 1986.

“The Speech of the Unknown”

Where did Manly P. Hall uncover the tale that made such an impact on a president and his view of American purpose and destiny? In actuality, the episode originated as “The Speech of the Unknown” in a collection of folkloric stories about America’s founding, published in 1847 under the title Washington and his Generals, or Legends of the Revolution by American social reformer and muckraker George Lippard. Lippard, a friend of Edgar Allan Poe, had a strong taste for the gothic—he cloaked his mystery man in a “dark robe.” He also tacitly acknowledged inventing the story: “The name of the Orator. . .is not definitely known. In this speech, it is my wish to compress some portion of the fiery eloquence of the time.”

Regardless, the parable took on its own life and came to occupy the same shadowland between fact and fiction as the parables of George Washington chopping down a cherry tree, or young Abe Lincoln walking miles to return a bit of a change to a country-store customer. As with most myths, the story assumed different attributes over time. By 1911, the speech resurfaced in a collection of American political oratory, with the robed speaker fancifully identified as Patrick Henry.

For his part, Hall seemed to know little about the story’s point of origin. He had been given a copy of the “Speech of the Unknown” by a since-deceased secretary of the Theosophical Society, but with no bibliographical information other than it being from a “rare old volume of early American political speeches.” The speech appeared in 1938 in the Society’s journal, The Theosophist, with the sole note that it was “published in a rare volume of addresses, and known probably to only one in a million, even of American citizens.”

It is Hall’s language that unmistakably marks the Reagan telling. Indeed, there are indications that Reagan and Hall may have even met to exchange ideas. In an element unique to Hall’s version, the mystic-writer attributed the tale of the unknown speaker to the writings of Thomas Jefferson. When Reagan addressed CPAC he cited an attribution—of sorts: Reagan said the tale was told to him “some years ago” by “a writer, who happened to be an avid student of history. . .I was told by this man that the story could be found in the writings of Jefferson. I confess, I never researched or made an effort to verify it.” Here the president may have been referencing Hall.

Gnostic scholar Stephan A. Hoeller, for many years a close associate and friend of Hall’s, and a frequent speaker at PRS, affirmed the likelihood of a Reagan and Hall meeting. Hoeller told me that while he was on the Griffith Park campus of Hall’s Philosophical Research Society one day in 1971, early in Reagan’s second term as governor, he spotted a black limousine with a uniformed chauffeur standing outside it. Curious, he approached the man and asked, “Who owns this beautiful car?”

“At first,” Hoeller recalled, the driver “hemmed and hawed and then said, ‘Oh, it’s Governor Reagan—he is in meeting with Mr. Hall.” Hall’s longtime librarian, Pearl M. Thomas, confirmed the account to Hoeller. “They know each other quite well,” he recalled Thomas saying. She further told him that Reagan had “called him here at the office several times. But we are not supposed to talk about this.”

Hall was known for discretion and avoidance of Hollywood chatter and social climbing; there is no record of his speaking directly about the governor. But when Reagan began his ascent to the White House and his name arose in conversation, Hoeller recalled, the mystic smiled and said, “Yes, yes, we know him.”

Hoeller, a distinguished man of old-world bearing, eschews hyperbole. He concluded: “There are definitely several indications that there was contact and influence there.” The scholar’s recollections square with the timing of Reagan’s 1974 remarks before CPAC.

Nation Within

Given the fanciful nature of the “unknown speaker” and other of Hall’s treatments, one may wonder what worth, if any, the story—and Hall’s books on America—offer the reader of history. As suggested earlier, it bears recalling that myths, ancient and modern, reflect psychological truth and the teller’s self-perception, sometimes more than events themselves. Myths reveal who we aspire to be and warn against what we may become. Those on which we dwell disclose character.

With the tale of the “unknown speaker,” Hall captured an element of what philosopher Jacob Needleman (1934–2022) called “the American soul.” Reagan certainly thought so. The codes and stories in which Reagan spoke form the key to the enigmatic actor-politician—a fact intuited by President Gerald Ford (1913-2006), who called Reagan “one of the few political leaders I have ever met whose public speeches revealed more than his private conversations.” [5]

That being so, is there any “secret destiny of America” or “American soul”? Yes: within ideals. You do not read Manly P. Hall for a blow-by-blow of history—or the work of what he calls (somewhat cheekily) the “literal historian.” Rather, Hall saw human events as a transcendent arc of ideas. His work strives to decode meaning behind individuals and movements. Hall’s historical telling is sometimes parabolic—revealing internal currents and ideals of a certain time and place, including ours. Hall’s historicism helps us better understand America’s self-conception and locate new layers within it.

I close on a personal note. It seems to me that during this time of national chasm most of us share a sole point of agreement. America can withstand buffets, blows, and divisions provided one facet of its existence endures: protection of the individual search for meaning. I believe Manly P. Hall would have agreed.

Notes

[1] E.g., “Reagan and the Occult,” The Washington Post, April 10, 2010.

[2] E.g., see The Secret History of America: Classic Writings on Our Nation’s Unknown Past and Inner Purpose by Manly P. Hall, edited and introduced by Mitch Horowitz (St. Martin’s Press, 2019).

[3] E.g., see “The Rediscovery of Akhenaten and His Place in Religion” by Erik Hornung, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Vol. 29 (1992).

[4] E.g., see The Invisible History of the Rosicrucians by Tobias Churton (Inner Traditions, 2009).

[5] A Time to Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald R. Ford (Harper & Row, 1979).

The connection with Reagan to MPH is so interesting. I feel blessed to live practically around the corner from the PRS. I’m also intrigued by the theory that he was murdered by grifters… (https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-12-22-me-11645-story.html)

This is the kind of layered, careful work that’s rarely attempted—let alone pulled off. You walk the razor’s edge between respect for myth and accountability to the historical record without collapsing into the extremes of blind belief or cynical dismissal. I deeply appreciated how you gave Hall his due as a synthesizer of meaning, while also interrogating the romanticism and omissions that still echo in spiritual Americana today.

Your framing of Freemasonry not as a nefarious cabal but as a protective container for seekers resisting dogma was especially clarifying. I also found the inclusion of Prince Hall Masonry and the correction of its historical timeline incredibly important—not just as an archival point, but because it reframes how Black esoteric tradition was foundational, not marginal, to American spiritual identity.

You’re doing real excavation here—of ideas, symbols, and distortions that still shape our collective psyche. Thank you for not turning away from the mess and myth of it all.