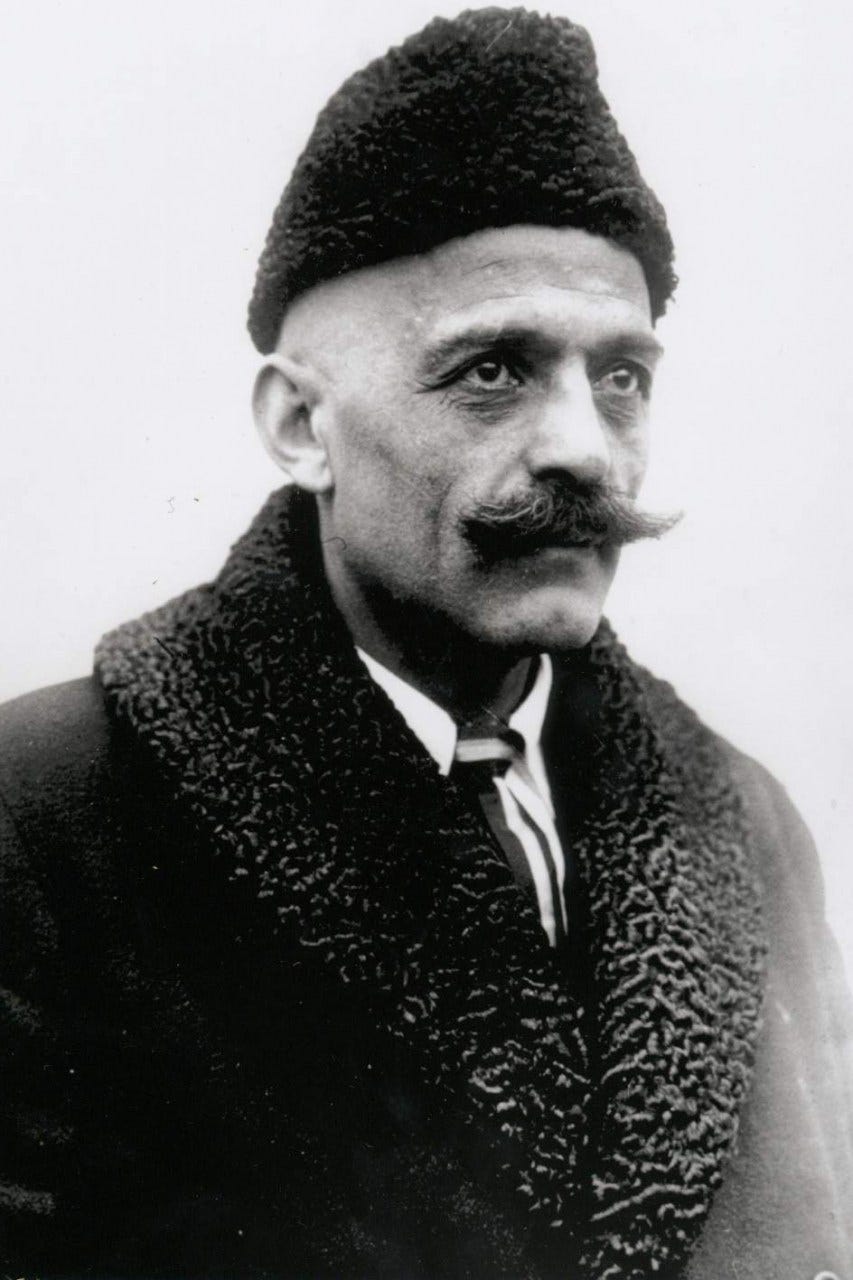

The mystery and message of G.I. Gurdjieff

An introduction to the saint of tough wisdom

One of the most seminally important and enigmatic spiritual figures of the twentieth century was Greek-Armenian philosopher G.I. Gurdjieff (1866–1949). His essential teaching is that man lives in a state of sleep—not metaphorically but actually.

Human existence, the teacher observed, is not only passed in sleep but man himself is in pieces, at the passive bidding of his three brains or centers: thinking, emotional, and physical, all of which function in disunity leaving a “man-machine” incapable of authentic activity.

“Man cannot do,” Gurdjieff said. He meant this in the fullest sense.

Nearly all of Gurdjieff’s statements—including his 1950 literary giant Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson—were intended to disrupt rote thought. He instructed that the magisterial allegory be read three times.

Author P.L. Travers, best known for the Mary Poppins books, noted aptly, “In Beelzebub’s Tales, soaring off into space, like a great, lumbering, flying cathedral, Gurdjieff gathered the fundamentals of his teaching.”

There is no neat summarizing the breadth of Gurdjieff’s system, which extended to sacred dances, self-observation, rigorous and challenging training and confrontation with obstacles, and what might be considered a cosmological-existential-spiritual psychology, explored by one of his greatest students, P.D. Ouspensky (1878–1947), who produced an invaluable record of his experiences with Gurdjieff, In Search of the Miraculous, posthumously published in 1949. A brief, though daunting, analysis also appears in Ouspensky’s The Psychology of Man’s Possible Evolution, published in 1950.

Appearing in Russia shortly before World War I, Gurdjieff assembled a remarkable circle of students, some of whom followed him in a harrowing escape across the continent amid the chaos and danger of war and revolution.

A sense of Gurdjieff’s relationship to his students and manner of teaching appears in an episode from Fritz Peters’ haunting and powerful 1964 memoir Boyhood with Gurdjieff.

In Peters’ book, the author recounts the commitment Gurdjieff exacted from Fritz at age eleven. The young adolescent met Gurdjieff in June 1924 when he was sent to spend the summer at the teacher’s school, the Prieuré, a communal estate in Fontainebleau-Avon outside of Paris.

Speaking to Fritz on a stone patio one day, Gurdjieff banged the table with his fist and asked, “Can you promise to do something for me?” The boy gave a firm, “Yes.” The teacher gestured to the estate’s vast expanse of lawns. “You see this grass?” he asked. “Yes,” Fritz said again. “I give you work. You must cut this grass, with machine, every week.”

Fritz agreed—but that was not enough. Gurdjieff “struck the table with his fist for the second time. ‘You must promise on your God.’ His voice was deadly serious. ‘You must promise that you will do this thing no matter what happens.’” Fritz replied, “I promise.” Again, not enough. “Not just promise,” Gurdjieff said. “Must promise you will do no matter what happens, no matter who try stop you. Many things can happen in life.”

Fritz vowed again.

Very soon, in the lives of Fritz and his teacher, something seismic and upending did occur. Gurdjieff suffered a severe car accident and for several weeks laid in a near-coma recovering at the Prieuré.

Fritz, feeling that the whole thing seemed almost foreordained, honored his commitment to keep mowing the lawns. But he met with stern resistance. Several adults at the school insisted that the noise would disturb Gurdjieff’s convalescence and could even result in the master’s death.

Fritz recalled how unsparingly the promise had been extracted and how fully it had been given. He refused to relent. He kept mowing—no one physically stopped him. One day while Fritz was cutting the lawns, he spied the recovering master smile at him from his bedroom window.

One of the greatest benefits students receive from Gurdjieff’s teaching (to which I can personally attest) is how it punctures, immediately and sometimes devastatingly, one’s cherished images of self.

We in the modern West are suffused with contradictions. People are filled with puffed up views of themselves. They are also filled with the opposite. But take one person and give him or her an unfamiliar task at an inconvenient hour and you will see how powerful or special we are. Not very.

Gurdjieff constantly pushed people to surpass their limits of perceived strength. In his posthumous memoir, Meetings with Remarkable Men, the teacher described episodes from when he and a band of students fled civil war-torn Russia. In an epilogue, “The Material Question,” he addressed their need for money.

In the summer of 1922, after a dangerous flight across Eastern Europe, Gurdjieff and his students reached Paris with razor-thin resources. Procuring an estate, the Prieuré, to function as living quarters and school, Gurdjieff used every means possible to foster his circle’s financial survival.

“The work went well,” he wrote, “but the excessive pressure of these months, immediately following eight years of uninterrupted labours, fatigued me to such a point that my health was severely shaken, and despite all my desire and effort I could no longer maintain the same intensity.”

Seeking to restore his strength through a dramatic change in setting as well as fundraise for the institute, Gurdjieff devised a plan to tour America with forty-six students. The troupe would put on demonstrations of the sacred dances they practiced and present Gurdjieff’s lectures and ideas to the public. Although intended to attract donors, the ocean voyage and lodgings entailed significant upfront expenses. Last-minute adjustments and unforeseen costs consumed nearly all the teacher’s remaining resources.

“To set out on such a long journey with such a number of people,” he wrote, “and not have any reserve cash for an emergency was, of course, unthinkable.”

The trip itself, so meticulously prepped and planned for, faced collapse. “And then,” Gurdjieff wrote, “as has happened to me more than once in critical moments of my life, there occurred an entirely unexpected event.” He continued:

What occurred was one of those interventions that people who are capable of thinking consciously—in our times and particularly in past epochs—have always considered a sign of the just providence of the Higher Powers. As for me, I would say that it was the law-conformable result of a man’s unflinching perseverance in bringing all his manifestations into accordance with the principles he has consciously set himself in life for the attainment of a definite aim.

As Gurdjieff sat in his room pondering their troubles, his elderly mother entered. She had reached Paris just a few days earlier. His mother was part of the group fleeing Russia but she and others got stranded in the Caucasus. “It was only recently that I had succeeded,” Gurdjieff wrote, “after a great deal of trouble, in getting them to France.”

She handed her son a package, which she told him was a burden from which she desperately wished to be relieved. Gurdjieff opened the package to discover a forgotten brooch of significant value that he had given her back in Eastern Europe. He intended it as a barter item used to pass a border or secure food and shelter. He assumed it was long since sold or otherwise traded and never again thought of it. But there it was. At the precipice of ruin, they were saved.

“I almost jumped up and danced for joy,” he wrote. This was the lawful result of “unflinching perseverance.”

As with all Gurdjieff wrote and said, there is at the back of his statement a level of gravitas and lived experience that makes this teaching warranting of deep pause. Things that might appear homiletic in the mouth of a lesser figure took on life-and-death seriousness from this teacher.

I close this brief consideration with a statement of Ouspensky’s. It is not, perhaps, considered one of his most remarkable observations, but it is useful and instructive insofar as it demonstrates how his and Gurdjieff’s ideas cannot be contextualized within familiar categories. Philosopher Jacob Needleman (1934–2022), a student of the Gurdjieff work, remarked, “It’s not like anything.”

Ouspensky made a valuable observation about the nature of a “positive attitude” in a talk reproduced in the posthumously published book, A Further Record: Extracts from Meetings 1928–1945. In its lowest and least useful iteration, Ouspensky told students,

. . . a positive attitude does not really mean a positive attitude, it simply means liking certain things. A really positive attitude is something quite different. Positive attitude can be defined better than positive emotion, because it refers to thinking. But a real positive attitude includes in itself understanding of the thing itself and understanding of the quality of the thing from the point of view, let us say, of evolution and those things that are obstacles. Things that are against, i.e., if they don’t help, they are not considered, they simply don’t exist, however big they may be externally. And by not seeing them, i.e., if they disappear, one can get rid of their influence. Only, again it is necessary to understand that not seeing wrong things does not mean indifference; it is something quite dif- ferent from indifference.

What the teacher is saying, albeit on a great scale, is that the individual must seek to understand forces that develop or erode his or her humanity, itself an immense question.

We are unconcerned with coordinates of good or bad, happy or sad, but rather with questions of developmental forces and what they mean to us.

______________________

This talk expands on themes of Gurdjieff’s thought, including those found in Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson.

I appreciate that your scholarship doesn't shy away from the difficult stuff. It's easy to promote Neville, whose clarity of thought and strength of conviction are easy to grasp. Gurdjieff seems like it's level 10 to Neville's level 1. No less worth exploration, but man. Man. Which book do you recommend one (one being me) start wrestling with first?

It details my connection to the Fourth Way and when I met someone who had met Gurdjieff.