Although he died in relative obscurity in 1972, mystic Neville Goddard (1905–1972) now ranks among the twenty-first century’s most widely followed writers and lecturers in alternative spirituality.

Search results for the mononymous Neville’s talks number in the millions. His books, once relegated to literature tables at New Thought churches (and even then difficult to find)—populate countless editions which, along with an expanding catalogue of anthologies, amass yearly sales of hundreds of thousands in print, audio, and digital.

Across Neville’s vast range of lectures, which he freely permitted audience members to tape-record in a dawning age of portable technology—a foresight that secured his legacy in the digital era—the teacher contended with unfailing simplicity and elegance that everything you see and experience is the out-picturing of your emotionalized thoughts and mental images.

“The only God,” the radical idealist told audiences, “is your own wonderful human imagination.”

Neville’s literary career began in 1939 with his slender, evocative volume, At Your Command. It is not only the mystic’s first book but among his most elegant and powerful statements in a career that spanned more than ten volumes and thousands of lectures.

With disarming brevity, At Your Command presents Neville’s full-circle philosophy: Your imagination is the creative force called God in Scripture; the Bible itself is neither historical nor theological but rather a symbolic blueprint of the individual’s psychological development.

“Every man,” Neville said in a lecture of October 23, 1967, “is destined to discover that Scripture is his autobiography.”

It is idealist philosophy—or what might be called spiritualized objectivism—taken to the razor’s edge, argued with jewel-like precision. However often Neville restated his basic premise, it always sounded fresh, reaching even repeat listeners and readers as though for the first time—a gift possessed by Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986), Vernon Howard (1918–1992), and few others.

ABritish native of Barbados, Neville first ventured to the U.S. at age seventeen to study theater. He had never before left his island environs. Although the graceful, angular youth found some success on screen and stage, he radically changed directions in the early 1930s when he said he began studying under a mysterious teacher named Abdullah, a turbaned black man of Jewish descent. The seeker said they worked together in New York City for five years poring over Kabbalah, number symbolism, and Scripture.

Despite Neville’s screen-idol looks, there exist few images of him. Some students thought him a man of mystery. One of Neville’s most dedicated acolytes in the mid-1950s was Margaret Runyan (1921–2011), cousin of American storyteller Damon Runyon (1880–1946) and briefly wife to New Age icon Carlos Castaneda. Margaret recalled in her 2001 memoir, A Magical Journey with Carlos Castaneda:

. . .it was more than the message that attracted Carlos, it was Neville himself. He was so mysterious. Nobody was really sure who he was or where he had come from. There were vague references to Barbados in the West Indies and his being the son of an ultra-rich plantation family, but nobody knew for sure. They couldn’t even be sure about this Abdullah business, his Indian teacher, who was always way back there in the jungle, or someplace. The only thing you really knew was that Neville was here and that he might be back next week, but then again. . .

“There was,” she concluded, “a certain power in that position, an appealing kind of freedom in the lack of past and Carlos knew it.”

It is not a stretch to reckon that Neville’s description of tutelage under an arcane teacher—a common theme in Western occultism since Madame H.P. Blavatsky’s (1831–1891) late-19th century claims of guidance from hidden Masters—informed Castaneda’s fanciful but undeniably penetrating narratives of mentorship to a Native American sorcerer.

At times, however, Neville opened up about his private life and how he responded to disappointing or bitter episodes.

In one instance, the lecturer recounted a painful incident from his drama school days, when he was fresh from the Caribbean and new to city life. In a late-career lecture of March 17, 1972, Neville described suffering humiliation by his acting teacher—but using the experience as a goad to something greater.

As you read his words, note that the youthful Neville probably spoke in a rounder, more rural Anglo-Caribbean accent—versus his later clipped and mellifluous diction—which his instructor deemed a career-killer:

My own disappointments in my world led up to whatever I am doing today. When the teacher in my school, I could ill afford the $500 that my father gave me to go to this small school in New York City, and she made me the goat. She called me out before an audience of about forty students. And she said, “Now listen to him speak. He will never earn a living using his voice.”

She should not have done that, but she did it—but she didn’t know the kind of person that she was talking about. Instead of going down into the grave and burying my head in shame, I was determined that I would actually disprove her. It did something to me when she said to me, “you will never earn” to the class—using me as the guinea pig to show them what not to do—and so, she said, I spoke with a guttural voice and I spoke with this very heavy accent, and I will never use my voice to earn a living.

We all went to this school and this teacher simply singled me out to make some little, well, exhibition of what I should not be doing in class. But I went home and I was so annoyed that I had lost my father’s $500 or $600 that he gave me for the six-months course, but I was determined that she was false, that she was wrong. So, I went to the end. I went to the end and actually felt that I was facing an audience and unembarrassed that I could talk and talk and talk forever without notes, no notes.

By early 1938, Neville quit his theatrical career to dedicate himself to writing and lecturing on metaphysics. As noted, Neville is not only one of the most widely heard spiritual orators of the twentieth century but he spoke extemporaneously and elegantly across decades worth of lectures, without a note in sight.

Although Neville wrote fuller works with greater metaphysical exposition, At Your Command remains the perfect user’s manual. What you experience, Neville told seekers, is not what you pray for but what matches your “awareness of being.” Clarified desire, properly directed, he said, catalyzes a new state:

For instance; if you were imprisoned no man would have to tell you that you should desire freedom. Freedom, or rather the desire of freedom would be automatic. So why look behind the four walls of your prison bars? Take your attention from being imprisoned and begin to feel yourself to be free. FEEL it to the point where it is natural — the very second you do so, those prison bars will dissolve. Apply this same principle to any problem.

Mere solipsism? The difference between a solipsist and an idealist is that the former burdens others to validate his self-image. Neville’s system is fiercely independent. Wishful thinking? Neville’s outlook evolved into what I consider the most elegant mystical analogue to quantum theory—and is increasingly recognized as such.

Speaking at a series of Los Angeles lectures in 1948, often published under the title Five Lessons, Neville announced: “Scientists will one day explain why there is a serial universe. But in practice, how you use this serial universe to change the future is more important.”

In an era before the popularization of quantum theory, it was a striking observation. It was not until years later that quantum physicists began discussing the many-worlds theory, devised by physicist Hugh Everett III (1930–1982) in 1957.

For his part, Everett was attempting to make sense of some of the extraordinary findings emergent from about three decades in quantum mechanics. For example, scientists are able to demonstrate, through interference patterns, that a subatomic particle occupies a “wave state” or state of superposition—that is, an infinite number of places—until an observer or automatized device takes a measurement: it is only when measurement is taken that the particle collapses, so to speak, from a wave state into a localized one. Before measurement is taken the localized particle exists only in potential.

Some argue that the “wave state” is nothing but a probability formula—it is certainly that, too (extraordinary in itself)—but I believe I am accurately stating what has been observed in the last ninety-plus years of particle experiments.

Indeed, starting about twenty years ago, it became fashionable for New Agers and laypeople, like me, to put quantum theory at the back of cherished spiritual principles. It became equally fashionable for professional skeptics and mainstream journalists to pushback, crying B.S. and sophistry. That position, while still heard, has quieted. Not because skeptics have grown more pensive or attenuated to media-speak, but because the proposition of mind-over-matter, strange as it may seem, now resounds in debates on theoretical physics in mainline journals and magazines.

Since Neville exemplified his own philosophy, it is important to understand something about him personally. Let’s pick up where we began earlier: the island of Barbados, where Neville was born in 1905. He was not a scion of the island’s wealthy, landowning class. Rather, he was part of a large, somewhat scrappy family of British merchants. They ran a small grocery and provisions business.

Transplanted from his tropical home to the streets of New York City, Neville led a precarious financial life. When theater jobs ran dry, the actor and dancer found work as an elevator operator, shipping clerk, and department-store salesman. He did land some impressive roles, including on Broadway. But most stage opportunities vanished with the onset of the Great Depression. He often wore the same suit of clothes and bounced around shared rooms on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Food was not a guarantee.

After Neville’s speaking career took off, syndicated gossip columnist Jimmie Fidler reported on May 4, 1955, that the Barbadian came from an “enormously wealthy” family who “owned a whole island” in the Caribbean. This is invention — but over time, and in line with stories Neville told himself, the Goddard family did, in fact, grow rich.

The clan of green grocers expanded into Goddard Enterprises, which is now a publicly traded catering and food service employing about 6,500 people in the Caribbean and Latin America. Neville’s father Joseph, called Joe, founded the business, and ran it with Neville’s older brother Victor, of whom Neville spoke frequently in his lectures. Indeed, everything Neville related about the rise of his family’s fortunes matches business records and reportage in Caribbean newspapers. But there is a more dramatic example of Neville’s self-descriptions cleaving to fact.

In the years immediately before and after World War II, Neville lived in New York’s Greenwich Village, a place he relished. He resided with his wife, Catherine Willa Van Schumus (1907–1975), nicknamed Bill, and daughter Victoria (1942-2024), or Vicky, at 32 Washington Square, a handsome, redbrick apartment tower on the west side of Washington Square Park. (The mystic’s prospering family had since put him on a stipend.) Neville recalled many happy years in the building, which still stands.

Like millions, he was pulled away from home by the draft in late 1942, just under a year into America’s entry to World War II. In lectures, however, Neville described using the powers of visualization to gain an honorable discharge a few months later and return home.

Why would the U.S. Army release a healthy, athletic man—Neville was lithe and fit as a dancer—at the height of the war effort when nearly every able-bodied male was mobilized? At age thirty-seven, he was a little old for the draft but well below the cutoff of forty-five.

In his accounts, the metaphysician wanted no part of the war. He was newly married with a four-month-old daughter and also had an eighteen-year-old son, Joseph, from a prior marriage. He had obligations most draftees did not. While stationed for basic training, the buck private requested a discharge—and was abruptly shut down.

Neville said he determined to use his methods of mental creativity. Each night, as he described it, he laid on his army cot and before drifting to sleep pictured himself home in Greenwich Village. He would see from the perspective of being in his apartment and strolling Washington Square Park. He continued, night after night, in this imaginal activity. (In lectures, Neville variously described his meditations lasting eight nights or as one vision on the first night of his request marked “approved” and then waiting nine days for his honorable discharge, which arrived on day ten.)

After eight nights, Neville said, seemingly from nowhere, his commanding officer summoned him and asked, “Do you still want a discharge?” Neville said, “I do.” The CO continued, “You’re being honorably discharged.”

I questioned this story and decided to verify it.

U.S. Army Human Resources Command provided Neville’s service records. The one original document remaining is his final pay statement, which, along with digital archives, shows his enlistment from November 12, 1942 to March 1943 with the 490th Armored FA Battalion at Camp Polk, Louisiana. A spokesman for Army Human Resources Command confirmed that Neville was honorably discharged in about four months in March 1943. The reason, as recorded by the military, is that the conscript was released “to accept employment in an essential wartime industry.”

I asked: “This man was a metaphysical lecturer—how is that a vital civilian occupation?” The spokesman replied: “Unfortunately, Mr. Goddard’s records were destroyed in the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center,” about a year after Neville’s death.

On September 11, 1943, The New Yorker confirmed Neville being back on the lecture circuit in a surprisingly extensive profile, “A Blue Flame on the Forehead”—the last time mainstream letters took any note of the mystic.

I cannot say precisely what happened; I can only report that Neville described the logistics accurately. I must add that if any quotidian reason exists for Neville’s honorable discharge, it may be a mistake in his draft records. Neville’s Electronic Army Serial Number Merged File lists his marital status as “separated, without dependents.” This is obviously incorrect. Yet the correction of this error does not mesh with official reasons for his discharge.

Across years, I have reviewed census data, citizenship applications, military documents, and other sources that track Neville’s whereabouts and employment and can only say that his self-professed timelines and life details match the available record.

The one facet of Neville’s career I have been unable to verify is his mentorship to the mysterious Abdullah, a man for whom there exists no definite paper trail beyond Neville’s descriptions.

A commercial fortune teller called “Prof. Abdullah” occasionally appears in period newspapers but it is important to note that sundry “seers” widely populated the New York scene, often adopting Eastern or arabesque names. One or more “Abdullah” in the press does not make a match.

I have considered whether Neville’s Abdullah may be found in the more impressive persona of a 1920s- and ’30s-era black-nationalist mystic named Arnold Josiah Ford. Like Neville, Ford was born in Barbados, in 1877, the son of an itinerant preacher. Ford arrived in Harlem around 1910 and established himself as a leading voice in the Ethiopianism movement, a precursor to Jamaican Rastafarianism.

Both movements held that the East African nation of Ethiopia was home to a lost Israelite tribe that had preserved the teachings of a mystical African belief system. Ford considered himself an original Israelite and a man of authentic Judaic descent. Like Abdullah, Ford was sometimes considered an “Ethiopian rabbi.” Surviving photographs show Ford as a dignified, somewhat severe-looking man with a set jaw and penetrating gaze, sometimes wearing a turban, just like Neville’s Abdullah, with a Star of David on his lapel. Ford himself cultivated an air of mystery, attracting “much apocryphal and often contradictory speculation,” noted historian Randall K. Burkett in his Garveyism as a Religious Movement (Scarecrow Press, 1978).

Ford lived in New York City at the same time that Neville began his discipleship to Abdullah. Neville recalled his and Abdullah’s first meeting in 1931, and U.S. Census records show Ford was living in Harlem on West 131st Street in 1930. In his study The Black Jews of Harlem (Schocken Books, 1964, 1970), historian Howard Brotz wrote of Ford: “It is certain that he studied Hebrew with some immigrant teacher and was a key link” in communicating “approximations of Talmudic Judaism” from within the Ethiopianism movement. This would fit Neville’s depiction of Abdullah tutoring him in Hebrew and Kabbalah. (It should be noted that early twentieth-century occultists often loosely used the term Kabbalah to denote any kind of Judaic study.)

More still, Ford’s Ethiopianism possessed a mental metaphysics. “The philosophy,” noted historian Jill Watts in God, Harlem U.S.A.(University of California Press, 1992), “. . .contained an element of mind-power, for many adherents of Ethiopianism subscribed to mental healing and believed that material circumstances could be altered through God’s power. Such notions closely paralleled tenets of New Thought . . .”

Ford was also an early supporter of black-nationalist pioneer Marcus Garvey and served as musical director of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. Garvey, as documented in my 2009 Occult America, suffused his movement with New Thought metaphysics and phraseology.

The commonalities between Ford and Abdullah are striking. Yet too many gaps emerge in Neville’s and Ford’s backgrounds to allow for a conclusive leap. Records of Ford’s life grow thinner after 1931, the year he departed New York and migrated to Ethiopia, where he died in 1935. Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, after his coronation in 1930, offered land grants to any African Americans willing to relocate to the East African nation. Ford accepted the offer. The timing of Ford’s departure is the biggest single blow to the Abdullah-Ford theory. Neville said he and his teacher had studied together for five years. This obviously would not have been possible with Ford, who had apparently left New York in 1931, the same year Neville said he and Abdullah first met.

Was there a real Abdullah? On this count, an enticing and notable testimony exists.

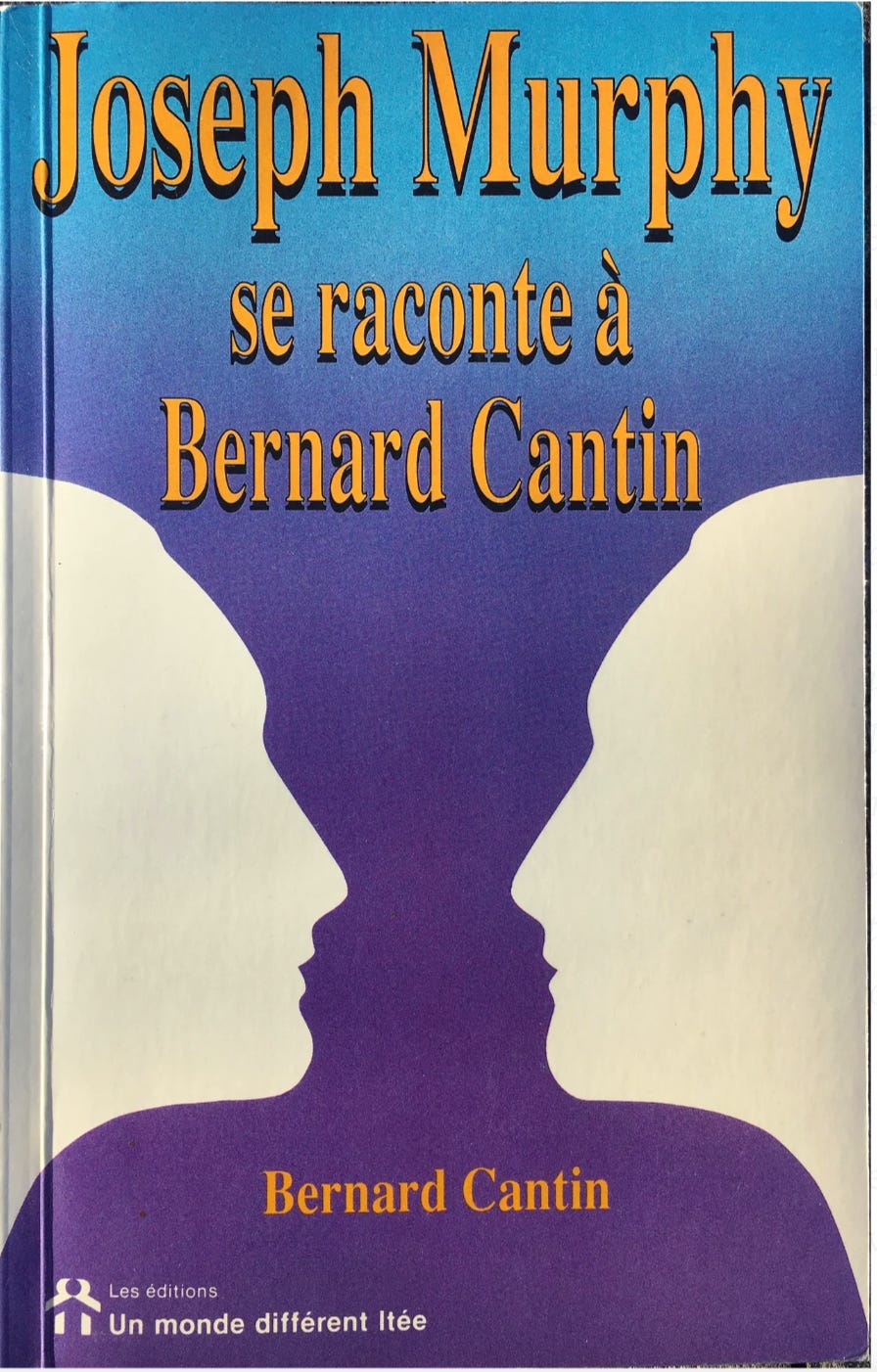

In the final year of his life, bestselling metaphysical author and minister Joseph Murphy (1898–1981) told an interviewer that he studied in the 1930s with the same teacher who tutored his friend and contemporary New Yorker, Neville. It was a turbaned man of black-Jewish descent named Abdullah.

In 1981, Murphy sat for a little-known series of interviews with French-Canadian writer Bernard Cantin, who in 1987 published the French language work Joseph Murphy se raconte à Bernard Cantin [Joseph Murphy Speaks to Bernard Cantin]. It has never appeared in English. Murphy described his experience with Abdullah, as recounted by Cantin:

It was in New York that Joseph Murphy also met the professor Abdullah, a Jewish man of black ancestry, a native of Israel, who knew, in every detail, all the symbolism of each of the verses of the Old and the New Testaments. This meeting was one of the most significant in Dr. Murphy’s spiritual evolution. In fact, Abdullah, who had never seen nor known the Murphy family, said flatly that Murphy came from a family of six children, and not five, as Murphy himself had believed. Later on, Murphy, intrigued, questioned his mother and learned that, indeed, he had had another brother who had died a few hours after his birth, and was never spoken of again.

In a letter of June 1987, reproduced below, Murphy’s second wife Jean, told Cantin that his interviews with her husband were the only to have received the metaphysician’s approval in the past thirty years.

Although he won audiences on both coasts by his death in 1972, it was difficult to fathom that the Barbadian’s voice, persona, and ideas would resonate in future decades. Indeed, the Woodstock Generation displayed little interest in the silver-maned, tailored man who spoke of the promethean power of imagination.

Conflicting accounts exist around Neville’s death. The most widely heard is that on October 1, 1972, Neville “collapsed and died of an apparent heart attack” at age 67 in his West Hollywood home, as reported in The Los Angeles Times on October 4, 1972.

In actuality, Neville’s death certificate from the state of California provides a different record, which squares with an account from one of his intimates, driver and friend Frank Carter, who was the last person to be with the mystic on the night of his death. (Neville’s wife was hospitalized at the time.)

Neville’s daughter Vicky summoned Carter to the teacher’s home to consult with the coroner the morning of October 1 when his body was found. In the coroner’s presence, Carter witnessed a massive amount of blood around Neville’s corpse and a contorted expression on his face, as though he had choked and bled out. (See Neville Goddard: The Frank Carter Lectures from Audio Enlightenment, 2018.)

According to his death certificate, Neville died of a rupture of the esophageal varices—i.e., swollen or enlarged veins—leading from the throat to stomach with subsequent hemorrhaging, hence the profusion of blood and appearance of choking. The cause was liver damage or cirrhosis. That condition generally results from long-term alcohol abuse.

“The coroner kept asking me what happened,” Carter recalled, “he said, ‘Was Mr. Goddard a heavy drinker?’ and his daughter said, ‘Well he used to be, but not lately.’” At a dinner party the night before, Carter recalled, Neville did not even finish a full martini, nor did the men have anything further to drink when he dropped Neville off at home.

Yet Neville often spoke of enjoying alcohol, including a bottle of wine each day with lunch. In a lecture delivered on an unknown day in 1972, he remarked, “I had my full bottle of wine today with some cheese for my lunch, and thoroughly enjoyed a bit of wine and, oh, a section of Edam.”

I do not view the teacher, or any artist, in a lesser light for his probable cause of death, and I realize, too, that there exist symbolical or extra-physical interpretations of Neville’s passing, some referenced by Carter, which I honor in the outlook of every mature seeker. Indeed, Neville referred to his own demise occurring, as it did, in his sixties, in a lecture delivered November 21, 1969: “In my own case this little garment seemed to begin in 1905, but it was always so. It was always growing into manhood and departing in its sixties. Always appearing, occupied by God, moving towards a certain point and then disappearing.”

Since many readers and listeners describe their experience of discovering Neville’s work in catalytic terms, I want to share my own story.

I am often drawn to a teaching based on my perception of its purveyor’s character and gravitas. Something about Neville’s persona gripped me even before I heard his clipped Anglican accent or glimpsed his Romanesque image. Neville, to me, conveyed personal seriousness intermingled with the most radical proposition I had ever heard: everything is ultimately rooted in you, as you are rooted in the infinite.

I initially wrote about Neville in early 2005 in an article for Science of Mind magazine. My article “Searching for Neville Goddard” was the first journalistic portrait of the mystic since occult philosopher Israel Regardie profiled him in his 1946 book, The Romance of Metaphysics. My boss, himself a New Thought minister, needled me that I was only interested in the teacher due to his obscurity—Neville was then a figure of opaqueness to most New Thoughters—and that my article might find commensurate readership. I used his comments in the same way that Neville used his drama teacher’s. As it happened, the article ignited a Nevillelution.

Just hearing Neville’s name filled me with intrigue. In summer 2003, I was interviewing major-league pitcher Barry Zito, who was then playing for the Oakland A’s. Barry’s tough-talking but idealistic father, Joe, had tutored his son in Neville’s work. The Cy Young Award-winner used Neville’s method of mental creativity in his training regimen. Pitching for the San Francisco Giants, Barry became the hero of the 2012 World Series.

Neville’s teaching that all of reality is self-created—that your mind is God the Creator —then formed a key part of the athlete’s system of self-development, which he inherited from both his father, Joe, and mother, Roberta, who led their own metaphysical congregation in San Diego, Teaching of the Inner Christ Church.

Midway through our conversation, Barry paused and said, “You must really be into Neville.” I had no idea what he meant. The athlete was incredulous. Immediately following our talk, I sought out Neville’s 1966 book Resurrection, his last. Upon reading it, I was enthralled—and hooked ever after.

Neville’s books were then available only in nondescript editions with plain beige covers. They were issued from a single publisher in Los Angeles, DeVorss & Co. (At Your Command was not among them—it recirculated only after Neville’s resurgence.) The covers were uniform in design, featuring title, author, and the intriguing insignia of an eye impressed on a heart impressed on a tree. Neville told a Los Angeles audience in 1948: “It is an eye imposed upon a heart which, in turn is imposed upon a tree laden with fruit, meaning that what you are conscious of, and accept as true, you are going to realize. As a man thinketh in his heart, so he is.”

The austere editions, more suited to Cato the Elder than a dramatic mystic, inadvertently heightened the mystery around the man. The volumes also opened a generation of readers—me included—to Neville’s ideas when virtually no other entry point existed.

A final word about Barry Zito. After my article appeared, his father Joe instilled me with confidence in my writing, still a new endeavor. At my desk at a publishing company one morning, I heard that Joe Zito was on the phone. Knowing Joe’s glass-eating reputation, I lifted the receiver nervously. In drill-sergeant tones, the voice on the other end announced: “Mitch, you stick with this thing!” He meant writing. I followed Joe’s exhortation. In a little over three years, I had my first book contract with Random House.

IfI had to reduce Neville’s method to its barest simplicity I would say that the teacher’s approach to life, perhaps imported from his thespian days, is to always be on stage. Feel and occupy the life you wish to experience; immerse yourself within that life in your mental-emotive self or psyche. Do so through emotive visualization, employed particularly in states of meditation or comfortable drowsiness when the rational defenses of the intellect slacken.

Author and magician Alan Moore has spoken eloquently of the connection between fiction, language, and magic. Moore has mentioned—and I can affirm—that anyone who’s been writing for a while has a file of extraordinary coincidences in which experience follows story. Concepts of “make believe” are powerful in ways one may not suspect.

IfI have any critique of Neville’s techniques, it is that I am unsure he realized how difficult it is for an individual to enter and sustain a feeling state contrary to dire circumstances or emotional duress.

Thought alone cannot produce emotion—emotion overpowers thought. Were thought or intention able to control passion, much less physicality, we would have no addictions, untoward outbursts, or depleting attachments. As a trained performer, Neville found it natural to summon different emotional states, similar to an accomplished Method actor. Those abilities are unavailable to most people.

Resolution to this dilemma is private for every seeker. One workaround, which the teacher often referenced and which I suggested earlier, involves using hypnagogia (not his term)—the state of cognizant pre-sleep or drowsy relaxation—to facilitate the feeling process. Hypnagogia naturally occurs twice daily: just as you are drifting to and rousing from sleep. It is a period of hallucinatory sentience during which you are nonetheless capable of controlling attention. What’s more, your rational barriers are lowered. This may be considered primetime to visualize a desired end. (Hypnagogia is also a period of heightened extrasensory-perception (ESP) activity, as recorded in academic psychical research.) This is similar to the methods of French mind theorist Émile Coué (1857–1926), whose phraseology appears in Neville’s work.

Hypnagogia is not necessarily limited to sleeping and waking hours. In Neville’s telling, he entered this state daily at 3 p.m. following lunch—aided by a full bottle of wine. Neville required no abstemiousness in his system. Whether excessive consumption of alcohol also proved the teacher’s undoing is a valid and somber question.

Another way of using Neville’s system is to adopt an inner state of theatrical or childlike play. Not childish, childlike: a state of internal wonder and pretending. Children excel at this. We grow embarrassed by this quality as we age but Neville spoke ingenuously of walking the wintry streets of Manhattan imagining that he was in the treelined, tropical lanes of his native Barbados, boarding a ship to some desired destination, or in a location where he wished to be.

Neville cautioned against rationalizing exactly how your wishes will arrive. Again from At Your Command:

Your desires contain within themselves the plan of self-expression. So leave all judgments out of the picture and rise in consciousness to the level of your desire and make yourself one with it by claiming it to be so now.

Unfoldment, he wrote, occurs in “ways beyond knowing”—harmonious, natural, and appropriate. In that vein, desires are neither to be feared nor conditioned:

The measurements of right and wrong belong to man alone. To life there is nothing right or wrong. . .Stop asking yourself whether you are worthy or unworthy to receive that which you desire. You, as man, did not create the desire. Your desires are ever fashioned within you because of what you now claim yourself to be.

When a man is hungry (without thinking), he automatically desires food. When imprisoned, he automatically desires freedom and so forth. Your desires contain within themselves the plan of self-expression. . .

The reason most of us fail to realize our desires is because we are constantly conditioning them. Do not condition your desire. Just accept it as it comes to you. Give thanks for it to the point that you are grateful for having already received it — then go about your way in peace. . .But, to be worried or concerned about the HOW of your desire maturing is to hold these fertile seeds in a mental grasp, and, therefore, never to have dropped them in the soil of confidence.

This relates to an observation by twentieth-century spiritual teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti, which is that when we ask how we really do not want something. How is avoidance. When the realness of desire exists, without conflict or contradiction, the means appear—albeit sometimes after an interval—as naturally as shooting open an umbrella in the rain. The hungry person desires food—not thoughts of food. This must be kept in mind when assuming your feeling state. And finally:

Recognition is the power that conjures in the world. Every state that you have ever recognized, you have embodied. That which you are recognizing as true of yourself today is that which you are experiencing.

Neville’s voice, even in his nascent work, summons us, finally, beyond all method, system, or liturgy. Above all, the teacher emphasized the literalness of a truth whispered in nearly every spiritual, therapeutic, and ethical philosophy: you are as your mind is.

I had intended to end this article on those words. But I am moved to a different conclusion, or at least an afternote, due to a letter I received as I was wrapping this piece. Such communications often arrive propitiously. It came from a reader and seeker, Irfan Tarin, on whose words I close with his permission:

I am from Afghanistan but living in Toronto since three years. I traveled to west in search to find answers for my questions. I have accidentally got to know about the “Infinite Potential” book of Neville Goddard. . .I don’t know how to say, I am so happy after reading this book, and feel a great relief and expansion since I started reading this. Specially the mystical experiences. And the real meaning of scriptures and verses which are same both in Bible and Quran. Like God made man in his own image or all the stories of prophets and messengers and all the book. Which nobody told us the real meaning.

We in the West tend to take the search for granted. The opportunity is all but handed us at birth. Human nature often devalues what is freely given. Consider Irfan’s words a gift—a reminder of your freedom to search. Use it.

No matter the avenues I travel I always am brought back to Neville. Perhaps because he draws the most truthful (to me) definition of God.

This is wonderful, Mitch. And so thoroughly fleshed out. I especially applaud the correlation drawn between Neville’s performance history and the ease in which he declared occupying states or “the wish fulfilled” — a thought I’d drawn a long time ago though rarely seems to be discussed amongst his fans and followers.

As a born and bread Bay Arean — the Zito bits are wildly entertaining and wonderful personal anecdotes. This was a joy to read.

Brilliant and Timely ‼️👏 Thank you!