Notes on a Lost Boy

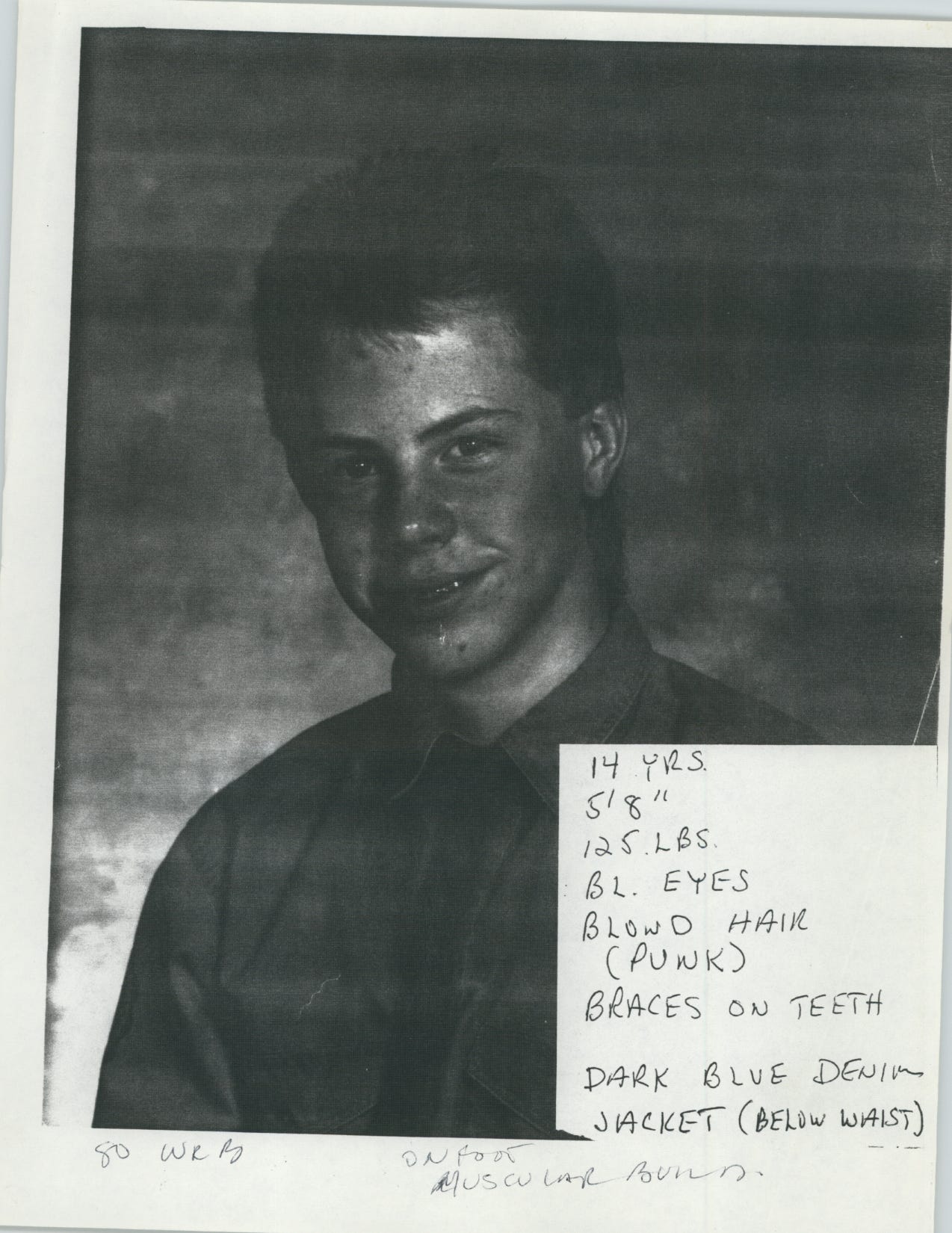

Tommy Sullivan, Jr., was a folk Satanist and a kid living amid dysfunction—who never got justice

“It has long been remarked that the gods of a conquered people become the devils of their conquerors.”—Witchcraft by Charles Alva Hoyt

It was a cold case made for our true-crime obsessed era: A New Jersey teen attending a Catholic school develops an interest in Satanism and brutally kills mom and self on the winter night of January 9, 1988.

It was the height of the Satanic Panic, the media and legal frenzy over a nationwide epidemic of reputed Satanic-abuse crimes. Waves of accusations resulted in hundreds of shocking prosecutions, busted trials, and overturned imprisonments emerging from later-exposed falsehoods in the media, legal system, and among self-appointed therapeutic experts, many of whom were found to plant, coerce, or otherwise encourage lurid and discredited testimonies from children or recovered memories from vulnerable adults.*

Amid this fetid atmosphere—and, in this case, with forensic and circumstantial evidence—police brass rubberstamped and quickly shut the investigation.

Younger officers were not so sure. Was the alleged murderer Tommy Sullivan, Jr., age fourteen, suffering domestic or other abuse? How does an adolescent with no record of violence or evident psychosis, armed only with a pocketknife, brutally beat and stab to death his mother? And—more hauntingly—how does that adolescent, sitting in a neighbor’s snowy yard, slit both of his wrists and sever his throat with a gashing wound that nearly removes his head—all with a Boy-Scout knife?

Questions linger. Was Tommy the killer? Was there an accomplice or goad? Did Tommy, Jr., really end his own life in such bizarre circumstances—and how? Is it physically possible? Why was his father, Tommy, Sr.—the only adult home the night of the deaths—never investigated? There is no evidence of abuse at Tommy’s school. Nonetheless, New Jersey’s five dioceses settled hundreds of claims of sexual abuse allegations from that period.

For all that, there existed a simple answer: blame Satan. Tommy developed his own folk religion of Satanism. His interests seem to have begun after a school paper on comparative faiths, including his descriptions of Satanism, though in negative terms.

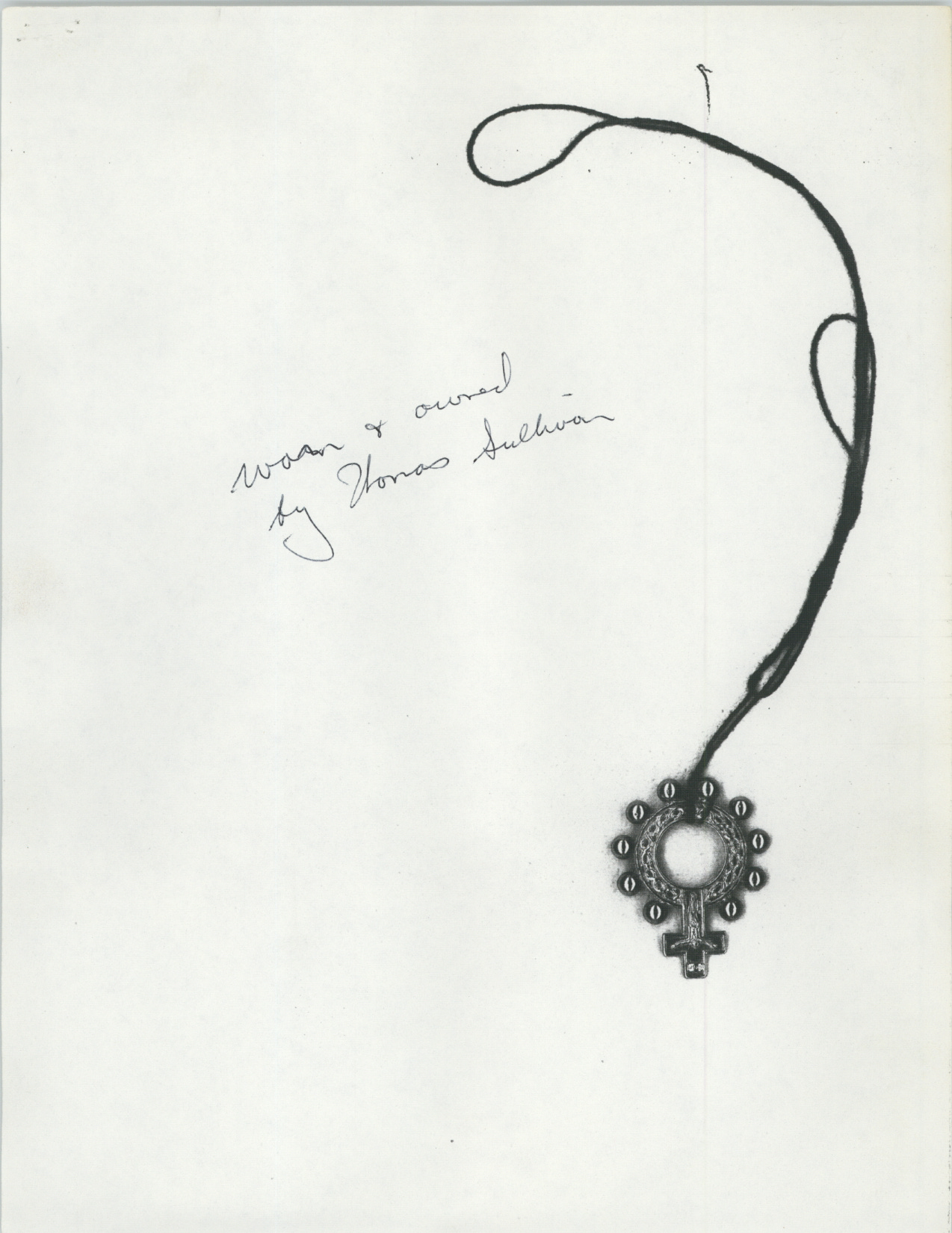

Tommy soon wrote out vows to serve Satan and asked friends to join him. His notebooks abound with his conceptions of Satanic imagery, fed, in part, by occult-themed books (including that quoted in the epigraph) from the public library. He used gothic script, sometimes written backwards. In in one pact, Tommy committed to eventually killing his family—but later amended: “I have already killed my family.” (He allegedly started a fire in the family living room, replete with some of his occult volumes, following his mother’s death.)

I participated in a recent docuseries on the alleged murder / suicide that was supposed to address the lingering unknowns. It began encouragingly. I signed legal paperwork that limits some of what I can say in this commentary. It is written solely on my own steam. The show’s final cut, after positing meaningful questions, defaulted to the straight story—and, in my view, committed one more disservice to victims and community.

There were, to be sure, valuable elements. In addition to innovative use of miniatures, the docuseries featured dignified, well-paced interviews with law enforcement, educators, and friends. It culminated, however, with two extended exceptions: a “local pastor” (of whom scant trace appears online) and a criminologist-therapist—both unconnected to the crime—who, in on-camera exposition, ventured personal theories and suppositions.

Through tears, the pastor tied Tommy’s alleged murder-suicide to the supernatural—claiming that his own eight-year-old daughter attempted suicide at the urging of Tommy’s apparition. This went unchallenged. I have two sons. If one attempted suicide at age eight and I blamed a maleficent spirit, I would expect scrutiny.

As I saw it, the criminologist, speaking with the metronome efficiency of an expert witness, propounded, nearly forty years later without investigatory involvement, on Tommy displaying psychosis, belying the adolescent’s functional behavior reported by friends and school administrators. Let there be no doubt: officials at Tommy’s Catholic school voiced alarm over his Satanic interests and his proselytizing of them. But he participated in ordinary class activities.

The first policeman on the scene had serious questions about Tommy, Sr., knowing more than he said. The initial responding officer believed the father displayed suspicious behavior and unjustified certainty of his son’s guilt.

The father had not searched the home—he ran across the street for help. He had no obvious means of knowing whether his son had been abducted or was perhaps hiding in the house. There existed too many unknowns for him to decisively finger Tommy, Jr., who evidently attempted a bungled escape in the family car—now stuck in a snowbank with Tommy missing.

The show cast no light on the forensics of Tommy’s apparent suicide. His body was discovered in a neighbor’s yard the next morning. The series repeated the official story that Tommy had slit both wrists—and then his throat to the point of near-decapitation with a pocket knife. A lone set of footprints in the snow is the primary factor supporting suicide. No forensic authorities appeared on camera.

I located a letter from the May 2008 Weird NJ from an admirable police official and one of the interviewees, Paul Hart, a now-retired detective for the Jefferson Township Police Department. “I arrived on the scene shortly after the discovery of Mrs. Sullivan,” Hart wrote, “and worked closely on the case representing the local police agency along with our other detectives.” He continued:

Obviously many questions went unanswered, and the suggestions of satanic influence made the big time newscasts for the next several days . . . I found myself a much requested speaker at various formal and informal training sessions—primarily from law enforcement and educational groups, but also TV, radio, etc. It was a large part of my work over the next several years, until my retirement in 1992.

I had the opportunity to address all the issues mentioned—music, videos, games, books, his drawings and writings, etc.—and interact with a variety of people interested in learning more about our case. They wanted to know what we had learned and if it could help them. My audience from time to time also included witches, wiccans and satanic priests (formal and self-appointed). We all got along fine and without incident. Why? Simply because I never approached this tragic crime as “The devil made him do it . . .” It wasn’t a blame game or religious crusade. All the evidence certainly pointed to a very unhappy and disturbed adolescent boy struggling in a family which, in my opinion and that of other investigators, had its own dysfunctional situation going on.

Hart voiced several questions, concluding:

And yes, think about what would have happened if we had found a still armed Tommy on that dark, cold winter night, or the questions asked and possible answers given. Maybe an interview that would have resulted in a far different perspective and better understanding of exactly what had taken place and the true nature of the tragic death of a mother and son.

No one has answers. But Hart’s is the voice that frames the questions.

Did Tommy, Jr., kill his mother? Very likely. Did he kill himself? Unknowns linger. Did other factors exist—e.g., abuse, coercion, unseen family dynamics? Almost certainly.

Rather than address or simply sustain these questions, the show employed two extended closing interviews to propound familiar themes: sensationalistic, sometimes entertainment-derived, definitions of Satanism and postmortem diagnosis of psychosis.

We may never know what fully happened on that January night in 1988. But more is owed both victims and community.

** E.g., see “It’s Time to Revisit the Satanic Panic” by Alan Yuhas, New York Times, March 31, 2021; “I’m Sorry” [the recantation of a former child witness] by Kyle Zirpolpo as told to Debbie Nathan, Los Angeles Times, October 30, 2005; and “Why Satanic Panic never really ended” by Aja Romano, Vox, March 31, 2021.

Thanks for writing this, Mitch. I was the same age as Tommy in 1988, and grew up very close to Jefferson NJ where this occurred. Trying to figure yourself out at that age is really tough, and always wondered if his friends had tried to help him. In hindsight it’s just so sad. At some point, one of the police offers involved in the case spoke at my church youth group and it scared the crap out of me…contracts with ‘The Devil’…possessed to the point of severing tendons…was definitely scary to a Catholic kid who had the pants sacred off of him by ‘The Exorcist’ and ‘The Omen’ films…There are a lot local legends about the area… the infamous ‘Clinton Castle’ and ‘Clinton Road’ come to mind, and if you’ve read any issues of Weird NJ, you have most likely come across them.

I’d heard this case discussed on a couple of podcasts, but your analysis brings a level of clarity and seriousness that was missing elsewhere. You separate fact from panic without losing sight of the real tragedy, and the nuance here is deeply appreciated.