What Is Evil?

Its meaning is not convenient

Evil. A big word. Used too often. (Like love.) What is it?

We all have pet definitions. Usually, not always, they revolve around the premise of what makes me afraid. Or of what I absolve myself of but blame on another.

G.I. Gurdjieff (c. 1866-1949) observed that the totality of man’s lived philosophy is “I like” and “I do not like,” “I want” and “I do not want.” I see no reason to challenge that.

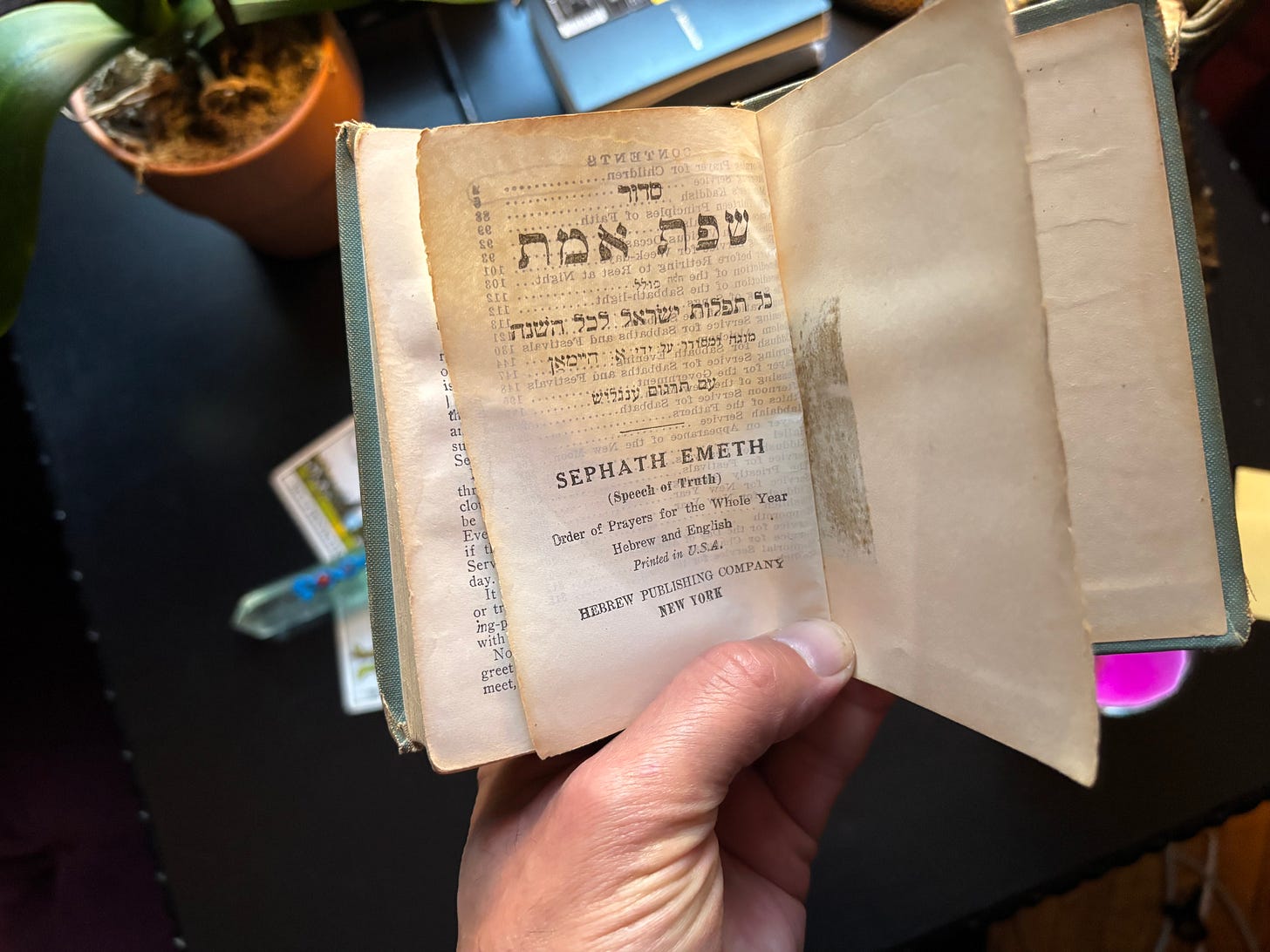

In the Talmudic digest Pirkei Avos (“Ethics of the Fathers”), a master tells his students: “Go and see which is the worst quality a man should shun.”

One of them, Rabbi Simeon, replies: “One who borrows and does not repay. It is the same whether one borrows from man or from God.”

Another disciple, Rabbi Elazar says, “An evil heart,” meaning greed and spite. The master, Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, pronounces those the best words, “for in his words yours are included.”

Amalgamizing these principles, another disciple, Rabbi Yosé, later comments: “Let your friend’s property be as precious to you as your own.”

Life Is Debt

What does it mean to borrow and not repay? This question prompts the colloquialism Talmudic: the point can be argued so serpentinely that its meaning grows obfuscated. Or, in the hands of a real student, deepened.

To avoid obscuration or over literalism, I offer a single dimension—and, I think, the chief dimension, the space between two points—of what it means to borrow and not repay.

Life is debt. Unseen, unknowable, and multitudinous causes underlie my existence. I have not earned them. No one reading these words is free from that principle.

On a quotidian scale, the very device on which these words are being read, whether phone, desktop, or some other, was produced through human suffering: workers unevenly paid, irreplaceable minerals harvested from Earth, disposable batteries fated to poison someone’s soil, and so on. Think of how infinitesimal a fragment of debt is referenced.

Debt occurs transactionally, too—my greater concern here for its immediacy. I recently green-lit publication of a book that I thought was in public domain. I fancy myself a copyright expert. For the first time in my career, I was wrong.

In Neil Gaiman’s Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader?, Batman’s death is depicted in a multiverse. In one panel, the Dark Knight muses: “Sometimes I fall in battle. Sometimes I die hugely, bravely, saving the city . . . Sometimes it’s a small, ironic, unnoticed death—I die rescuing a child from a fire or tackling a frightened pickpocket.”

I will pay back every dollar of damage for my oversight.

We must pay for our existence, including damage we cause.

Don’t Blame Me

I detest those who shirk their debts—or, worse still, ascribe them to others. I used to laugh in my publishing days as an acquiring editor. Whenever someone did not deliver his or her book (or heaven forbid return the money), it was, inevitably and always, my fault.

Of all the people whose books I contracted and who did not finish them, exactly one took responsibility and repaid the money. That was Tucker Carlson. There is no politics in my comment. But mark it in context of this article.

And what of the term borrowing? Aren’t we all doing that? From every fragment of coal to every nuclear explosion, we are using the source of the sun. This has formed the basis of religious devotions across time. Esoterically, that is a manner of recognizing debt.

Why Are You Alive?

I realize that even my narrow framing of this principle can branch off in endless directions. “What about a nation’s debt? . . . What about . . .?” I will say that our debt as a species warrants consideration. If you knew how many animals suffered and died for your uplifting, you would make a whole new measure of your life. Writing of laboratory uses of animals, philosopher William James (1842-1910) noted somberly of a vivisected dog: “his sufferings are having their effect—truth, and perhaps future human ease are being bought by them.”

Properly felt, this history should drive me to my knees. That is debt.

Likewise the suffering of ancestors whose journey to this place—and the people that earlier migrants displaced—put me in debt. Others have perished, directly or indirectly, so that I exist. That is debt.

A small means of payment is desisting from complaint, especially within.

Piety Does Not Pay Debts

I hesitate, however, to wax too broadly in this matter. Overreach is avoidance. People who bang the loudest drums about global justice (or religious goodness) are, as a rule, the least likely to help you move, smile at a child, water a houseplant, or rescue you from real trouble.

They judge, they do not love, if there is such a thing. I have never experienced a modicum of love, joy, or uplift from grim keepers of tabs over who occupies the “right side of history.”

In the same James essay, which is unsigned from The Nation, he notes the valiant New Englanders who stifle research over concern for animal rights yet benefit from “a community which boils millions of lobsters alive every year to add a charm to its suppers.” I am borrowing when I write this passage, which appears fundamentally (with different emphasis) in Russell B. Goodman’s “Thinking About Animals” in the 2016 Nordic Wittgenstein Review. That, too, is debt.

Honor Priorities

Part of debt means giving things their due at the proper time and place. “If you don’t give something its right attention now,” philosopher Jacob Needleman (1934-2022) told me, “it will take all of your attention later.”

This principle has endless applications but it must include raising of children and caring for loved ones. The night I began this essay, I delayed dinner for a recovering person. My excuse was the artist’s need to capture lightning in a jar. The consequence was petty neglect. Perhaps the two intermittently coexist.

But my debt cannot be cleansed: “creativity” is, in its way, selfish.

In light of the principle I have cited—“one who borrows and does not repay”—evil is not a matter of religion, professed fealties, or social side-taking. It is conduct. All else is a dodge. Convenience is, in a banal sense, evil—especially when used to define evil.

That Day

Once upon a time, the New York Times published my critique of an academic who foolishly structured a study on restaurant responses to food-borne illness by writing letters to eateries falsely claiming illness. The result was near-panic among restaurateurs, all of whom expressed urgent concern. Only a social scientist who has never engaged in commerce could fail to foresee this.

The Times published my letter on September 11, 2001. I confessed with shame to my teacher that I actually felt rueful over my letter running that day—it would go unnoticed. “Why"?” he asked, challenging my shame. People are selfish and petty. We grab. I like. My stupidity is not evil. It is ordinary.

I collected donations that day at a Red Cross table. I grow emotional as I write these words. A young boy, perhaps age five, approached the table and handed me an envelope filled with nickels. He had broken open his piggybank. If there is any hope for humanity, which I doubt, it is that boy.

“No one,” Needleman told me, “could have taught him to do that.”

The boy understood debt. G.I. Gurdjieff called this a “magnetic center.” A political activist once told me that such references “sound like eugenics.” I said I would consider his statement. I did. I deem it the idiocy of categories—of sorting what we consider good and evil into familiarities.

I cannot repeat the boy’s story in public. I will cry. I do not know why. And I am not interested in reading why in the comment section. It is the nature of truth.

Another person approached me that day at the table. An older middle-aged woman. She said she had lost her home in the explosion. She’s lying, I thought. She was too monotone, not in the manner of someone in shock but rather of someone tentatively testing a statement or claim. A Red Cross worker factually confirmed my instinct. The woman, whatever her motive (I hardly care), wanted attention. On a day of suffering, she sought to take. It was a shade of difference from my selfishness—but a shade too far. I do not judge her. I measure.

My Bicycle Ticket

Several days before starting this article, I got ticketed in a sting operation when I pedaled my bike through a red-light intersection in Midtown Manhattan. I soon discovered that I could not pay my summons online but had to appear on a weekday morning at criminal court in Midtown (I live in Brooklyn).

This kind of court appearance is intended as a punitive measure, which falls disproportionally on wage-earning people and parents (or both) who must seek coverage for work or caregiving. I speak less for myself than for the bicycle delivery man whose living is earned almost solely through tips.

As I biked to court, I recalled the cop who ticketed me explaining that a lot of elderly people live in the neighborhood where I was pinched. Police were trying to reduce risks. A fair point. Still, I was not a happy camper.

I planned to plead guilty and tell the judge something about my general practice of bike safety, which is true. Maybe I would catch a break. But something interrupted my plans. As I docked my electric bike in Midtown on a chilly morning, I glanced over my shoulder and began walking across the bike lane onto the sidewalk. Like lightning, another cyclist (either on an ebike or racing bike) was on top of me. He yelled out in alarm and we collided—just. There were no injuries. “Yo, a little slower in Midtown, please,” I said. He did not turn around. Probably wise.

My excuses were done. I signed into the court roster and was directed to wait outside the building. A man stood among us complaining loudly to any who would listen about how city government was doing this just to suck up money. He reminded me of nearly everyone I grew up with. An officer came out and sent me home: it turns out, the police had not filed the complaint.

I draw no hokey karmic linkage between events. I note only: we always believe we are right. Chance suggests that is 50% correct. Before calling out someone as “evil,” gaze into the cracked mirror. In general, the person looking back has as much debt as the accused.

Evil then is not some maleficent, ultimate polarity. That description serves vanity. Evil is the shirking of what sustains my life.

Postscript: On Quoting Talmud

Due to the nature of our “I-heard-it-somewhere . . .” culture, even quoting Talmud is a fraught exercise. Misunderstandings abound. Hence, I reproduce a note I posted on X on January 31, 2025:

Friends, As some of you know, a lot of flawed info circulates on social media today about passages from the Talmud. I don’t know whether this brief comment will do much good—since brevity is what contributes to the problem.

It is important to note that the Talmud—in addition to its myriad and sprawling tracts and varying traditions—was constructed as a literary tabernacle for a nation in exile and, hence, some tracts reflect the same communitarianism as any work of the Hebrew Bible (i.e., Old Testament). The texts of the ancients, and their immediate inheritors, are not understood via excerpt.

One of the reasons the term “talmudic” entered the vernacular is because it connotes highly complex, tortuous parsing of a passage. This is what is required—and what the sages and students themselves felt was required. There exists no “literalist” meaning that easily discloses itself.

In that vein, observers sometimes post passages that—in isolation or absent commentary—appear pernicious. This perpetuates misunderstanding. A frequent example is Ketubot 11b. The tract’s intent is protecting the abused from being ineligible for marriage—not defending the perpetrator. (https://sefaria.org/Ketubot.11a.14?lang=bi)

If you wish to experience the ethical Talmud—i.e., the true meaning at its heart—read the short, immensely powerful volume Pirkei Avot or Ethics of the Fathers. (https://sefaria.org/Pirkei_Avot?tab=contents) [The phoneticism avot (“fathers”) is also rendered avos, as in this article. Both are the same. The pronunciation avot is Sephardic, i.e., Middle Eastern-North African-Persian, while avos is Ashkenazi, i.e., European.] It rescued me in adolescence (along with the Dead Kennedys, apologies to Mrs. Shapiro). There exist myriad translations of Ethics, with one linked immediately above.

I will share a parable (with my own emphasis) from Pirkei Avot 2:6: A student is walking in a cave and sees a skull floating in the dank waters. “How did you get here?” the student asks. “I used my words to drown others,” the skull replies, “and they returned to drown me.”

Beautiful work! I have not been following much since the long miracle course writings, having been consumed with being homeless in NYC for the last year, and doing bike delivery when it doesn’t obstruct the main goal of navigating the labyrinthine course, with its stops and starts, of seeking housing, meeting basic needs,etc.

This really has reminded me to see and think clearly when my mind is tired and broken and it seems easiest to judge and condemn to try and gain some sort of illusory control over the situation, rather than seeing clearly and maintaining my own ethics…

Thanks man, I really appreciate the decades of labor you’ve put in to even be able to write this

Secondly I like to comment on the subject of love. Love is the desire to not be alone, without all the trimmings and romanization. I think in a symbolic sense and it is my strongly held belief that, the universe was born out of this desire.

If a non-dualistic entity wanted to separate and divide itself; it would be for the sake of love and the chance of union. To loosely quote Crowley.

This article stirs a profound question in my mind.

Thank you Mitch.