Three-Step Miracle

How a little red pamphlet changed modern life—and may change yours

Once upon a time, I lived in a neighborhood, not unusual in New York City, where a homeless man from his regular spot at an intersection would yell at passersby.

One morning I approached him and said, “My man, check this out”—handing him a little pamphlet on mind-power metaphysics.

In a perfectly lucid, non-confrontational manner he asked, “What is this, positive-thinking stuff?”

Yes, I said. “I’m not really into that stuff.” I said I understood and left him with the pamphlet.

I have no idea (and doubt) whether he used it. But even the exchange created an opening. That little booklet, which I personally use, forms the topic of this article. -M-

____________________

Can thoughts make things happen?

A middle-aged Chicagoan who beat the Great Depression believed so—and he anonymously spread his mind-power secret to the world. His beguiling method, so deceptively simple, holds insights and surprises a century later.

One Simple Idea

The messenger of success concealed his identity behind the initials R.H.J., which stood for Roy Herbert Jarrett (1874-1937). By profession Jarrett was a salesman of typewriters and of printing machines. But the seeker-salesman accomplished what few ministers or practical philosophers ever could: He worked out an ethical philosophy of personal attainment, and couched it in everyday, immensely persuasive language. At age fifty-two Jarrett brought his message to the world in a self-published, pocket-sized pamphlet called It Works.

Published in 1926, Jarrett’s twenty-eight-page pamphlet has never gone out of print. It has sold nearly two million copies and remains popular—for good reason. It Works is among the most intriguing and infectious books ever written on mental manifestation. Anyone who wants to taste (or test) such ideas can finish Jarrett’s pamphlet during a lunch break. And many did.

Wage-earning Americans who had never before given much thought to metaphysics wound up buying and often giving away large numbers of It Works (I am among them) sending grateful testimonials to the address that Jarrett printed inside.

As legend goes at the front of the booklet, Jarrett had sent his short manuscript to a friend for critique. Jarrett identified the friend only by the initials “J.F.S.” The helper returned it with the notation: “IT WORKS,” which Jarrett adopted as his title.

The legend is true. The friend was Jewell F. Stevens, owner of an eponymous Chicago advertising agency, which specialized in religious items and books. In 1931, the advertising executive Stevens hired Jarrett to join his agency as a merchandising consultant and account manager. For Jarrett, the new position was deliverance from a tough, working-class background, and years of toil in the Willy Loman-domain of sales work. Jarrett became the example of his own success philosophy.

Salesman and Seeker

Roy Herbert Jarrett was born in 1874 to a Scottish immigrant household in Quincy, Illinois. His father worked as an iceman and a night watchman. Roy’s mother died when he was eight. By his mid-twenties, Roy was married and living in Rochester, New York, working as a sales manager for the Smith Premier Typewriter Company. His first marriage failed and by 1905 he returned to the Midwest to wed a new bride and live closer to his aged father. In Chicago, Jarrett found work as a salesman for the American Multigraph Sales Company. It was the pivotal move of his life.

American Multigraph manufactured typewriters and workplace printing machinery. In a sense, the printing company was the Apple Computer of its day. The company’s flagship product, the Multigraph, was an innovative, compact printing press. It took up no more space than an office desk and could be operated without specialized knowledge. The Multigraph was the first generation of easy-to-use printing devices, allowing offices and organizations to produce their own flyers, mailers, and newsletters. Its manufacturer possessed a sense of mission. American Multigraph had a reputation in the printing trade for its gung-ho culture and pep-rally sales conventions.

“For years,” wrote the industry journal Office Appliances in September 1922, “a feature of every convention has been an address on ‘The Romance of the Multigraph’ by Advertising Manager Tim Thrift.” On the surface, Thrift told his sales crew, the Multigraph could print labels, newsletters, and pamphlets—but one must peer into “the soul of what to some appears as a machine.” The Multigraph, he said, was “not a thing of metal, wood and paint; a mere machine sold to some man who can be convinced he should buy it. Ah, no! The Multigraph is a thing of service to the world...”

Cynics could laugh but for Jarrett the company’s motivational tone, combined with the magical-seeming effectiveness of modern printing, launched the idea of It Works.

Day by Day

Jarrett’s belief in inspirational business messages dovetailed with his interest in autosuggestion and mental conditioning. Such ideas reached him through the work of early twenetieth-century French mind theorist Emile Coué (1857-1926) who had visited Chicago on a speaking tour. Jarrett’s vision grew from a cross-pollination of American business motivation and the ideals of the French hypnotist-healer.

Born in Brittany in 1857, Coué developed an early interest in hypnotism, which he pursued through a mail-order course from Rochester, New York. Coué more rigorously studied hypnotic methods in the late 1880s with physician Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault. The French therapist Liébault was one of the founders of the so-called Nancy School of hypnotism, which promoted hypnotism’s therapeutic uses.

While working as a pharmacist at Troyes in northwestern France in the early 1900s, Coué made a startling discovery: Patients responded better to medications when he spoke in praise of the formula. He did so with accuracy—hitting upon a “transparent placebo” response validated a century ahead.

In January 2014, clinicians from Harvard’s program in placebo studies published a paper reporting that migraine sufferers respond better to medication when given accurate and “positive information” about an already-efficacious drug. This was the same observation Coué ventured.

Harvard’s study is considered a landmark because it suggests that the placebo response, whether for good or ill, is ever-operative. It marks the first study to use suggestion, in this case, news about a drug’s efficacy, in connection with an active versus inert substance, and hence, demonstrates that personal expectation (or belief) impacts how, and to what degree, we experience a drug’s benefits, or fail to.

Although the Harvard paper echoed Coué’s original insight, it made no mention of him. I contacted the director of Harvard Medical School’s program in placebo studies, Ted J. Kaptchuk, a remarkable and inquisitive clinician. “Of course I know about Coué,” Kaptchuk told me. He agreed that the migraine study coalesced with Coué’s observations.

In short, Coué came to believe that imagination aided not only in recovery but also general sense of well-being. From this insight, Coué developed his method of “conscious autosuggestion.” It is a form of waking hypnosis that requires reciting confidence-building mantras while in a relaxed or semiconscious state. Coué argued that many people suffer from a poor self-image. Our willpower, or drive to achieve, he said, is constantly overcome by our imagination, by which he meant a person’s unconscious self-perceptions.

“When the will and the imagination are opposed to each other,” he wrote, “it is always the imagination which wins. . .” By way of example, he asked readers and listeners to consider walking across a wooden plank laid on the floor, for most an easy task. But if that plank is elevated, say, twenty-feet from the ground, the task becomes fraught with fear even though the physical demand is unchanged. This, Coué said, is what we are constantly doing on a mental level when we imagine ourselves as worthless or weak.

Coué’s method of autosuggestion is simplicity itself. It requires repeating the confidence-building mantra:

Day by day, in every way, I am getting better an better.

The secret is in its application. Day by day must be recited twenty times each morning and evening, just loud enough to hear, while lying in bed just before drifting to sleep and again upon awakening. Eyes are closed, body is still, and mind is focused on what you desire. Coué advised using a string with twenty knots to count off the repetitions, as if counting rosary beads, to avoid rousing and thus distracting yourself. This recitation occurs during the highly suggestible state called hypnogogia when your mind is uniquely supple and suggestible. (French dream researcher and physician Alfred Maury (1817–1892) originated the term hypnagogia, which was popularized by psychologist Andreas Mavromatis in his like-named 1987 monograph). Later studies, widely replicated, show that hypnagogia is “prime time” for extrasensory perception (ESP) and telepathy.

The Magic Hand?

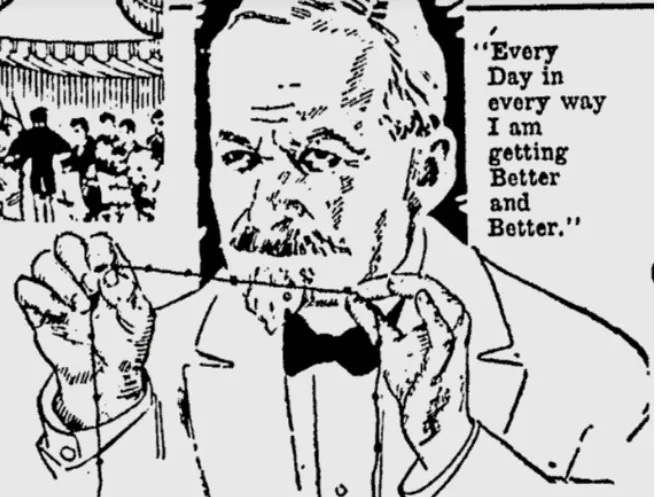

In the early 1920s, news of Coué’s method reached America. The “Miracle Man of France” briefly grew into an international sensation. American newspapers featured Ripley’s-Believe-It-Or-Not-styled drawings of Coué, looking like a goateed magician and gently displaying his knotted string at eye level like a hypnotic device.

In early 1923, Coué made a three-week lecture tour of America. One of his final stops in February was in Jarrett’s hometown, where the Frenchman delivered a talk at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall.

In a raucous scene, a crowd of more than two thousand demanded that the therapist help a paralytic man who had been seated onstage. Coué defiantly told the audience that his autosuggestive treatments could work only on illnesses that originated in the mind. “I have not the magic hand!” he insisted. Nonetheless, Coué approached the man and told him to concentrate on his legs and to repeat, “It is passing, it is passing.” The seated man struggled up and haltingly walked. The crowd exploded. Coué rejected any notion that his “cure” was miraculous and insisted that the man’s disease must have been psychosomatic.

To some American listeners, Coué’s message of self-affirmation held special relevance for oppressed people. The pages of black-nationalist Marcus Garvey’s newspaper Negro World echoed Coué’s day-by-day mantra in an editorial headline: “Every Day in Every Way We See Drawing Nearer and Nearer the Coming of the Dawn for Black Men.” The paper editorialized that Garvey’s teachings provided the same “uplifting psychic influence” as Coué’s.

Coué took a special liking to Americans. He found American attitudes a refreshing departure from Old-World attitudes. “The French mind,” he wrote, “prefers first to discuss and argue on the fundamentals of a principle before inquiring into its practical adaptability to every-day life. The American mind, on the contrary, immediately sees the possibilities of it, and seeks. . .to carry the idea further even than the author of it may have conceived.”

The therapist could have been describing the salesman-seeker Roy Jarrett. “A short while ago,” Jarrett wrote in 1926, the year of Coué’s death, “Dr. Emil Coué [sic] came to this country and showed thousands of people how to help themselves. Thousands of others spoofed at the idea, refused his assistance and are today where they were before his visit.”

But Jarrett saw the potential.

Three-Step Miracle

Taking his cue from the ease of Coué’s approach, Jarrett devised “Three Positive Rules to Accomplishment” in It Works. In sum, they are:

1. Carefully write a list of what you really want in life—once you are satisfied with it, read it three times daily: morning, noon, and night.

2. Think about what you want as often as possible.

3. Keep your practice and desires strictly to yourself. (This blocks other people’s negative reactions from sullying your inner resolve.)

Then, express silent gratitude each time an item on your list reaches you. Do not rationalize: whatever reaches you must, of necessity, travel established channels. Just express appreciation.

As Coué had observed about American audiences, Jarrett boldly expanded on the uses of autosuggestion. In the steps of American metaphysical tradition, Jarrett believed that subconscious-mind training did more than recondition thought: it activated a divine inner power that out-pictures one’s mental images into the surrounding world. “I call this power ‘Emmanuel’ (God in us),” Jarrett wrote.

With its ease of method, the self-published pamphlet quickly found an audience and ran through multiple printings. Many readers swore by it, and wrote in for additional copies to give away to friends something Jarrett, ever the salesman, encouraged with a bulk-order form.

That’s It?

It is tempting to look over Jarrett’s three steps and ask: that’s it? What reasonable person would attempt such a rudimentary, even childish, method to achievement?

Indeed, most detractors did not try it—and never came to understand why the little booklet became one of the most popular, if below-the-radar, works of spiritual self-help.

The booklet subtly directs us to do something we think that we do all the time but, in actuality, rarely try: come to terms with what we really want. I explore that common but confounding issue here:

We certainly believe that we know what we want. We constantly tell ourselves I’d like to buy that, work there, date him, and so on. But we rarely, if ever, sit down in a sustained and self-revealing way, stripped of all conformities and prejudices, and lay bare our truest, most absolute desires.

We may or may not want to act on those desires—there may exists costs and burdens, ethical or otherwise. There may appear unforeseen consequences or compromises. But just as often, we harbor within us a true, noble, and altogether sound life direction that we never articulate or attempt. This is because we are continually distracted by rote thought and internalized peer pressure. We we almost never stop—completely stop—to ask: What do I really want?

And there may be more to the “simple” formula in his little book than just that. The clarified, motivated mind may also possess an agency that we have not yet fully reckoned with in modern Western life, but that is indicated in placebo studies, neuroplasticity, quantum enigmas, and psychical research. There may be unacknowledged mental properties and possibilities that this three-step program sets in motion, or at least hints at. I explore these questions more fully here:

Sacred Symbol

Jarrett’s work broke through—yet he felt incomplete. It wasn’t that he chafed at using mind-power for material ends. Indeed, he urged readers to use the book for money, possessions, or just about anything they wanted. But he believed that many had missed the book’s deeper point. “Merely giving you the simple rules to accomplishment, with brief instructions as to their use,” he wrote several years later, “while beneficial, is not satisfying.”

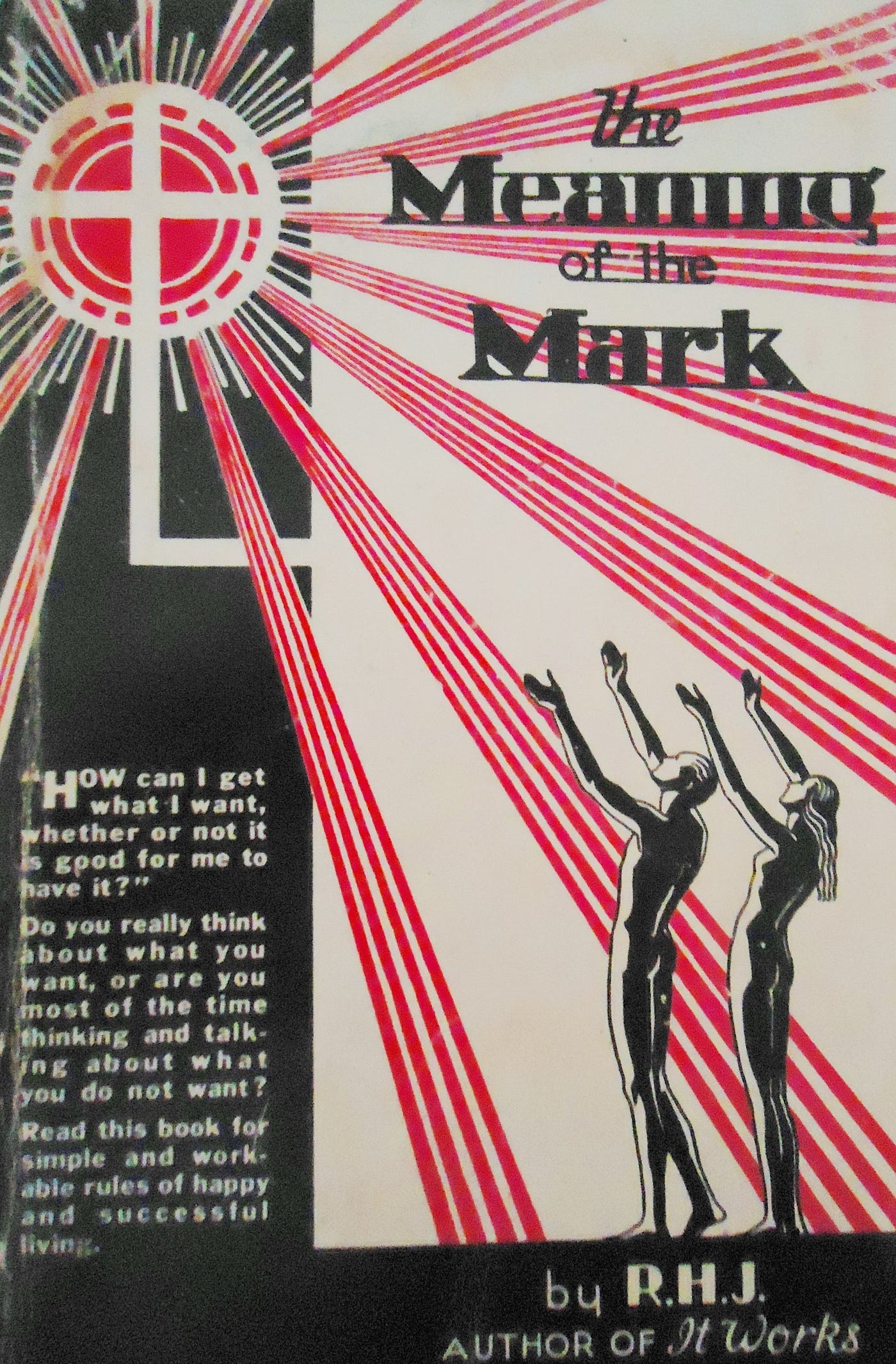

Jarrett’s deeper purpose in It Works was only hinted at by a mysterious symbol he placed on its cover. As seen on the vintage edition atop this article, below the title appeared a line drawing of a cross, with its bottom sharply curved at a right angle. The square-and-cross appeared on every copy of the little red book until 1992, when a Southern California publisher, DeVorss, which had since taken over the license, removed it. That symbol, wrote Jarrett’s friend Stevens, “was really the undisclosed reason for the book.”

What was this beguiling square-and-cross, which some readers ignored, some wondered at, and a publisher later cut?

Five years after producing It Works, Roy Jarrett ventured a little-known and final foray into publishing. In 1931, he produced a thoughtful and ambitious work, The Meaning of the Mark. The longer volume served as an inner key to It Works—it explained his strange symbol and dealt directly with the moral quandaries of success-based spirituality.

Jarrett explained that the cross-and-square was his personal symbol of spiritual awakening. Its meaning, he hoped, would be intuitively felt by readers.

The square represented earthly conduct, particularly treating others with the respect one seeks for oneself, which Jarrett saw as the hidden key to achievement. But there was another part to the matter. Personal attainment could find its lasting and proper purpose only when conjoined to the cross, the presence of God. Together, individual striving and receptivity to the Divine would bring man into the fullness of life. Jarrett wrote:

The definition of correct thinking for our purpose is: “thoughts which are harmoniously agreeable to God and man as a whole.” Thoughts agreeable to God come to you through the intuitive messages from your soul, often intensified by the senses. Thoughts agreeable to man come to you more frequently through the senses and are often intensified by intuition.

By dwelling on the meaning of the square-and-cross, he reasoned, the reader is constantly reminded to unite the two currents of life.

California Idyll

The success of It Works helped Jarrett attain a lifestyle that, while not extravagant, surpassed anything his laborer father could have known. Jarrett and his wife retired to a sunny hacienda-style bungalow in a middle-class section of Beverly Hills. But their California idyll proved short-lived. Jarrett died there in 1937 at age sixty-three of leukemia. He had been diagnosed three years earlier.

Jarrett did not embark on his career as a writer until the final years of his life. He produced both of his books while in his fifties. His success arose not despite the lateness of his start but because of it. This is a path I know:

Like British seeker James Allen and the best New Thought pioneers, this self-educated man from ordinary life devised a philosophy that had been tested by the nature of his own personal conduct and lived experience. Only then did he deem it worth sharing.

Notes on Sources

Virtually no biographical literature exists on Roy Herbert Jarrett. My account is assembled from sources including U.S. Census data for 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930; Los Angeles County birth and death records; Indiana state marriage records for 1900 and 1905; Rochester Chamber of Commerce Directory (1900–1901); U.S. copyright records and copyright data from various editions of It Works and The Meaning of the Mark; and Beverly Hills, California, real-estate records and listings.

Jarrett published It Works independently in 1926 under the Larger Life Library; in about 1948 the book was licensed to the Los Angeles–based publisher Scrivener & Co.; and by 1978 it was published by the California press DeVorss, which issues the pamphlet in its most familiar form today. These dates are sometimes difficult to pin down, as DeVorss also distributed the work at various points and records overlap among the various publishers. Sales estimates are based on information that Scrivener and DeVorss periodically provided to the book trade, along with an estimate of more recent sales through BookScan. Jarrett published The Meaning of the Mark in 1931 under his Larger Life Library; those rights, too, passed to Scrivener for a time beginning around 1948. Both works are now public domain.

Jarrett is reported joining the Jewell F. Stevens Company in the trade journal Printers’ Ink, May 14, 1931. For information on the American Multigraph Company I drew upon company brochures and users’ bulletins from 1919; “Multigraph Hundred Pointers Hold Big Convention,” Office Appliances, September 1922; “District Meeting for Multigraph,” Office Appliances, May 1927; and “Graphic Merger,” Time, November 24, 1930, from which Tim Thrift is quoted. Jarrett’s cause of death appears on his death certificate, dated August 28, 1937.

Emile Coué is quoted on will and imagination from his Self Mastery Through Conscious Autosuggestion (Malkan Publishing Co., 1922). Coué is quoted in Chicago from “Coué Proves Theory Worth,” Los Angeles Times, February 7, 1923 (I altered the article’s amusing use of the phonetic “ze” for “the” in its attempt to capture Coué’s French accent). Additional articles on Coué’s first American tour (he returned briefly in 1924) include “Crowd in Orchestra Hall Cheers Coué as His First Attempt in Chicago to Effect Cure Seems a Success,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 7, 1923; “Youth’s Tremors Quieted by Coué,” New York Times, January 14, 1923; and “Emile Coué Dead, a Mental Healer,” New York Times, July 3, 1926.

The headline from Marcus Garvey’s Negro World appeared September 15, 1923, and the editorial quote is from February 10, 1923—for both references I am indebted to Robert A. Hill’s Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, vol. 10 (University of California Press, 2006).

Coué is quoted on his American audiences from My Method, Including American Impressions (Doubleday, Page & Company, 1923). Additional sources on Coué include The Scientific Explanation of Mind Healing by Albert Amao, Ph.D. (Quest, 2014); The Practice of Autosuggestion by C. Harry Brooks (Dodd, Mead and Company, 1922); “Bypassing the Will: The Automatization of Affirmations” by Delroy L. Paulhus from The Handbook of Mental Control edited by Daniel M. Wegner and James W. Pennebaker (Prentice Hall, 1993); Suggestion and Autosuggestion by Charles Baudouin (George Allen & Unwin, 1920); “Emile Coué’s Method of ‘Conscious Autosuggestion’ ” by Donald Robertson, 2006-2009, posted at the website of the UK College of Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy; and The American Idea of Success by Richard M. Huber (Pushcart Press, 1971, 1987).

There exist myriad editions of It Works, which is now, as noted, public domain. I recommend a physical edition but the booklet can also be searched and read online.

If you liked this article, please consider a paid subscription:

"It Works" was probably the first metaphysical book I bought ,back in the mid-80s at a bookstore with the poetic but tongue twisting name of "Sphinx & The Sword Of Love" in Harvard Square., Cambridge. (Last time I checked it's now a realtor's office). It was a small pamphlet, sitting on the counter near the cash register, and it's what I could afford at the time. Initially I was almost disappointed at the simplicity of it. I figured if it was going to be changing lives and such it should be a bit more complex. :-) Well, all I can say is, "it works!". Thanks for the detailed information Mitch, you always come through! I'm now curious to read "The Meaning Of the Mark".

"Wisdom - Let us be attentive."