The Myth of Nazi Occultism

Academia and social media abound with claims of Nazism’s “occult” and “green” roots. The historical record tells a different story.

In late 2020, I was invited to sit in on a Zoom call of scholars, curators, and historians who were planning a Holocaust memorial monument in Ukraine. The session occurred just over a year before Putin’s invasion; in the time since, I have often wondered about the fate of some of those on the call that day.

I was invited by a friend, a distinguished curator, who was delivering a presentation to the committee. He spoke on primeval funerary traditions to examine how the ancients abided death, memory, and interment rites and whether such practices held ideas for the nature and design of the planned memorial. He discussed burial mounds, markers, and pyres, as well as numeric, calendric, and astronomical formulas used to calculate their direction and placement. The presentation was, in my estimation, thorough and brilliant.

When the floor opened, an eminent professor, from whom others seemed to be waiting to hear, spoke up in a rather dramatic way. “It is particularly ironic that you’re giving this presentation,” he told my friend, “because the Nazis were an occult and green movement. In fact, if Heinrich Himmler himself had been on this call he would have liked your presentation very much.”

Personally, I detected both extravagance and reductionism in his remarks. As a guest on the call, I did not feel it my place to enter a debate. My friend took the comments in great spirits. The following day he asked me, “Now that I’ve been named Heinrich Himmler’s favorite intellectual, what did you think of the talk?”

I thought highly of it, I said. But, I added, there exists today, in both academia and on social media, willful overestimation of the extent to which occult themes were present or doted upon within Nazi circles. In general, I believe we overdetermine the sources of Nazism. There existed little constancy, aside from nationalism and race hatred, within Nazi ideology; wide-ranging symbolic and historical material was embraced, copied, discarded, and contradicted.

Indeed, over-reading occult themes into Nazism is an easy trap to fall into because the Nazis, as with nearly all fascist and absolutist movements, made broad use of heraldry, symbolism, and pageantry, often of a primeval and archetypal nature. Occultism itself is a revivalist movement of ancient and readapted religious forms. Hence, when political movements harken backwards for heraldry and symbol, whether the eye-and-pyramid, obelisk, or grimmer repurposings, they look familiarly “occult.” (I define occult from its Latin root “hidden;” the term was adopted by Renaissance thinkers to reference pre-Christian spirituality.) These judgments, in my experience, are heightened by the general distaste many intellectuals feel toward occultism and metaphysics, which chafe against modern values of physicalism, replication, and classification.

Europe was suffused with competing ideologies in the early twentieth century and the impact of an occult revival appeared almost everywhere, including in the germination of abstract art through the second-generation Theosophical book, Thought Forms. Occult ideas sometimes spilled into social movements, both authoritarian-fascistic and democratic, with no definitive plurality in either.

But the Nazi-occult connection, not only for the reasons noted but due to general (and I aver prurient) fascination with the regime, sustains a popular thought current, appearing in scholarly works, like Eric Kurlander’s celebrated Hitler’s Monsters (Yale University Press, 2017), and popular media, such as podcasts, YouTube videos, and below-the-radar bestsellers.

An example recent to this writing appears in the widely read article, “Nazi Hippies: When the New Age and Far Right Overlap” by Jules Evans (Medium, September 4, 2020). Among its claims: “The Nazis were also huge fans of organic farming and of Rudolf Steiner’s biodynamic agriculture which sees farming as a mystical communion with the land and its spirits/energies.” Heinrich Himmler and Rudolf Hess were interested in organic farming—including Steiner’s methods—but Steiner’s movement of Anthroposophy was attacked and then banned in 1935 for its universalistic humanism.

Again: “The first ever institute devoted to parapsychology research—the Paracelsus Institute—was set up under the Nazis, at the Nazi-founded Reich University of Strasbourg.” Both Kurlander’s book and Anne Harrington’s Reenchanted Science (Princeton University Press, 1996) briefly reference “the Paracelsus Institute,” an idea hatched in 1942. J.B. Rhine’s Parapsychology Laboratory at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, was founded twelve years earlier.

The “green” charge is increasingly heard, which localizes to Nazism a sprawling fin de siècle movement ranging from back-to-nature and natural health to arts-and-crafts and physical culture. For fuller context, I recommend Eco-Alchemy: Anthroposophy and the History and Future of Environmentalism by Dan McKanan (University of California Press, 2017) who achieves an admirable blend of historical sensitivity and sharp critique.

That much said, the sympathetic critic—me included—must never propagate a defense of occultism, or any other philosophy, for the sake of perfumery; the full spectrum must be considered. Indeed, several early twentieth century proto-fascist movements seized upon esoteric ideas and symbols, including the Vedic swastika, from Madame H.P. Blavatsky’s 1888 opus The Secret Doctrine.

Movements that foster spiritually emancipatory attitudes often produce socially liberatory counterparts, such as: Spiritualism and suffragism, New Thought and democratic socialism, Freemasonry and abolitionism, Romantic-era Satanism and feminism, and Theosophy and the Indian independence movement. At the same time, movements that idealize “lost” or “hidden” traditions—which also include some I have just mentioned—can subtly degrade precious modern values, including democratic liberalism.

To meaningfully address occultism and politics, including extremist variants, requires definitions. The term “fascism” is commonly used and misused. Historically, I find three defining traits of fascism-authoritarianism, which extend to Nazism as well as other totalitarian movements, including Soviet-style Communism: 1) A compact of government, judicial, military, and economic power. 2) Some degree of national, racial, or class-based exclusivity, or a combination. 3) Pageantry: the mass rally, ceremony, badge, banner, flag, and national symbol. Usually, these symbols are intended to reinvigorate a sense of lost pride or grievance, either real or imagined, ethnic or economic. Indeed, a key feature of fascistic or undemocratic movements is conviction among those who hold power, such as national majorities, that they hold no power. Tapping this grievance, political actors offer programs, emblems, and slogans of national rebirth.

The Nazis exemplified this to the furthest extent. The most obvious representation of Nazism was the aforementioned swastika, an ancient Vedic symbol of eternal recurrence with no relation to nationalism or exclusivity. In Vedic literature, the swastika is a symbol of the individual’s continuity with the cosmos and all of life. At the same time, it must be stated plainly that racialist demagogues who formulated what became Nazi ideology almost certainly discovered this Vedic symbol in Madame Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine or direct offshoots of it.

As early as 1875, the Theosophical Society combined the symbol with other religious images — including the Egyptian ankh, star of David, and ouroboros (serpent swallowing its tail) — to fashion its organizational insignia. For Theosophy, the swastika represented karma and recurrence. Around its emblem revolved a Vedic maxim, added in 1880: There Is No Religion Higher than Truth. Yet a handful of racial mystagogues — including pan-German theorist Guido von List (1848–1919) — falsely conflated the swastika with images found in Germanic runes, which had been experiencing an early twentieth century revival. The symbol began appearing in Austrian occult journals as early as 1903.

List was a nationalist-racialist mystagogue who yearned to revive worship of Wotan, or Odin, and instigate resurgence of Nordic religion. In that vein, he can justly be called occult. Some of his followers coalesced around the Thule Society, which was connected to the early German Workers Party, the vehicle that eventually provided machinery for Hitler’s National Socialist movement. In this connection appears organizational lineage between an occultic and völkisch religious movement and Hitler’s early apparatus.

List was loosely part of a trend during the late-industrial age that favored getting “back to nature,” engaging in arts and crafts versus factory-made goods, and resuming the supposed idyls of rural versus urban life. This movement ventured both benign and corrupt expressions, as it was given to nostalgizing the distant past in opposition to consumerism and automation. With his eye for runes and symbols, it was probably List who laid hands on Madame Blavatsky’s introduction of the swastika to Western readers and who made its first decontextualization as an insignia for German rebirth.

Likewise, in the years preceding World War I, a handful of German pamphleteers and racial–mystical demagogues—List chief among them—seized upon the concept of the “Aryan” race, probably from The Secret Doctrine again. The term Aryan, as used by Blavatsky, also derived from Vedic literature, where it described some of the earliest Indian peoples. Competing notions of “Aryanism” began to appear in the late eighteenth century, but Blavatsky’s was among those that German occultists would most likely have heard of in the early twentieth century.

Blavatsky adapted the term Aryan to include the present epoch of human beings, which she classified as the fifth of seven “root races.” These races, like the cycles of Vedic yugas, stretch from the ancient past into the faraway future, eventually birthing a new branch of humanity, possibly exhibiting greater psychical or extraphysical development. Blavatsky was writing expressly in terms of spiritual evolution; at times, however, the smasher of convention lapsed into language that smacked of bastardized Darwinism or racial conventions of the day. [1]

For German racialists, the notion of a primordial race emergent from Asia had long been appealing: “If the Germans could link their origins to India,” wrote Joscelyn Godwin in his 1993 Arktos: The Polar Myth in Science, Symbolism, and Nazi Survival, “then they would be forever free from their Semitic and Mediterranean bondage” — that is, from Abrahamic lineage. How exactly Germany’s racial theorists came to conflate these patently Asian “Aryans” with their blond, blue-eyed ideal is the essence of muddled thinking. Especially since Blavatsky wrote that the Aryan race would reach its zenith in centuries ahead in America—a nation whose good character she unambiguously, if oddly, praised as, “owing to a strong admixture of various nationalities and inter-marriage.”

With these facts stated, the following cannot be made clear enough: Hitler was not a philo-occultist. He contemptuously dismissed the work of fascist theorists who dwelled upon mythology and mystico-racial theories. In Mein Kampf, he specifically condemned “völkisch wandering scholars”—that is, second tier mythically and mystically inclined intellects who might have belonged to occult–nationalist groups, such as the Thule Society, with which the Nazis shared symbols.

From the earliest stirrings of Hitler’s career in the German Workers’ Party and its street-rabble rallies, he was consumed with brutal political and military organization, not theology or myth. He employed a symbol as a party vehicle when necessary and immediately discarded the flotsam around it, whether people or ideas. He castigated those members of his inner circle who showed excessive devotion to Nordic mythology, dismissing the theology of Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg as “stuff that nobody can understand” and a “relapse into medieval notions!” [2]

Historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke (1953–2012), who I believe has done more than any other scholar to clarify these issues, noted:

Hitler was certainly interested in Germanic legends and mythology, but he never wished to pursue their survival in folklore, customs, or place-names. He was interested in neither heraldry nor genealogy. Hitler’s interest in mythology was related primarily to the ideals and deeds of heroes and their musical interpretation in the operas of Richard Wagner. Before 1913 Hitler’s utopia was mother Germany across the border rather than a prehistoric golden age indicated by the occult interpretation of myths and traditions in Austria. [3]

Under the Nazi regime, Theosophical chapters, Masonic lodges, and even sects that had produced some of the occult pamphlets a young Hitler may have encountered as a Vienna knockabout were shunted or savagely oppressed, their members murdered or harassed.

Despite astrology’s well-publicized appeal to a few of Hitler’s cadre, the ancient practice was effectively outlawed under Nazism, and many of its practitioners were jailed or killed.

The man sometimes mislabeled “Hitler’s astrologer,” Karl Ernst Krafft, had no contact with Hitler but briefly reached the attention of mid-level Reich officials for predicting the 1939 assassination attempt on him. Krafft later died en route to Buchenwald. Nazi authorities sentenced Karl Germer (1885–1962), the German protégé of British occultist Aleister Crowley, to a concentration camp on charges of recruiting students for Crowley, whom they branded a “high-grade Freemason.” [4] History has recorded a few self-styled magi or occult impresarios, like the philo-Hindu Savitri Devi, (born Maximiani Julia Portas) who, often from the safety of distant borders, venerated Hitler as a dark knight of myth. Those same figures would have suffered the fate of Krafft and Germer had they lived within the Reich’s reach.

What of the aforementioned Heinrich Himmler, Hitler’s deputy and an architect of the Holocaust? The Nazi officer was dedicated to reviving or reimagining certain Nordic or pagan ceremonies, which he saw as a replacement for Christianity. Indeed, he was impassioned to create initiatic orders, including the SS, and ceremonial liturgies that would replace Catholicism and Protestantism because, given the nature of fascism as I have described it, there could exist no alternate center of cultural or religious power. Hence, in Himmler’s machinations, a novelized and reconstructed Nordic spirituality—intimately wed to Nazism, extermination, antisemitism, racial exclusivity, and Germanic expansion—was envisioned to usurp extant churches and congregations.

As noted, some Nazi theorists, Himmler included, wanted to free the movement from perceived associations with Abrahamic religions. In that vein, starting in 1936 he sponsored the work of speculative archeologist Otto Rahn (1904–1939), whom he sent on excursions to Southern France and Iceland searching for the Holy Grail and links to a mythologized pagan past. Rahn was openly gay and ran afoul of SS brass who decided to add fiber to his spine by drafting him into guard duty at Dachau in 1937. Rahn was horrified, writing a friend, “I have much sorrow in my country…impossible for a tolerant, liberal man like me to live in a nation that my native country has become.” [5]

He quit the SS in early 1939, submitting his resignation to Himmler himself. Two weeks later, the bookish thirty-four-year-old was found frozen to death on a mountainside in Austria, whether by suicide or murder is unknown. Around that time, Himmler endorsed a new SS-led excursion into Tibet with the aim of unearthing mythical threads of Aryanism. Himmler also sponsored a pet project of leasing Renaissance-era Wewelsburg castle in the Northern Rhine region to serve as headquarters for an initiatory order within the SS, a fascistic revival of King Arthur’s Knights of the Roundtable. It was never acted on in a more than spotty way, according to most records, although esotericist and neofascist Julius Evola, who is soon met, apparently lectured initiates. [6]

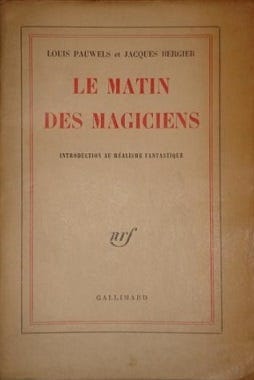

Personally speaking, I grew up during a period when these topics were of great interest on cable documentaries and in speculative books. But often whole garments were woven from spare threads. The urtext of this way of thought is an intriguing historical work, The Morning of the Magicians by Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier published in French in 1960 and translated into English in 1963.

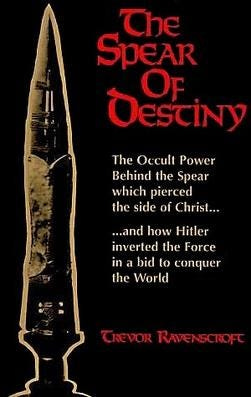

With a degree of artfulness, the authors introduce a wide variety of esoteric themes, including the Nazi-occult connection, which tapped the imagination of later writers. On this topic, Pauwels and Bergier were highly speculative, sometimes intentionally provocative, and inspired a wave of future literature and documentaries. Most of it descended in scale from their work, such as Trevor Ravenscroft’s widely read 1972 book The Spear of Destiny, an almost wholly imagined account of Hitler’s pursuit of the lance said to have pierced the side of Christ on the cross.

The case of Ravenscroft’s bestseller is ably settled by historian Stephen E. Flowers, Ph.D., who writes in The Occult in National Socialism (Inner Traditions, 2022):

the largely fictional character of the story told in The Spear of Destiny came out in a court case in 1980, when Ravenscroft sued novelist James Herbert for copyright infringement in the latter’s novel titled The Spear (1978). Ravenscroft asserted that the contents of his own book were fictional creations, and not historical material. Herbert had wrongly assumed that the material was actually a matter of history, and so not subject to copyright. The court ruled in Ravenscroft’s favor: the contents of The Spear of Destiny are indeed fictional. Evidence shows that Ravenscroft originally offered the book as a work of fiction, but the initial publisher preferred that it be cast as a historical reality.

It is important to note that the Nazi-occult theme began, and has continued, as a literary genre—heavily amped up following Pauwels and Bergier—which has left much of the public with the impression of settled history; this genre uses historicism as a device to support a foreordained thesis. This approach appears even in scholarly works like Kurlander’s Hitler’s Monsters, which relies on the apriorism of there being a Nazi-occult connection, thereafter filled in with historical episodes and stories, rather than foundationally arguing for one.

This tendency is again illuminated by Flowers, whose 2022 volume provides a valuable “Chronological Annotated Bibliography” of Nazi-occult literature from 1940 to 2017. Careful readers will note a paucity of scholarly or journalistic books on the topic, which, excluding fiction, is dominated by works of sensationalism.

Unlike Nazi racial theorists, controversial and fascist-adjacent Italian philosopher of esotericism Julius Evola (1898–1974) regarded “Indo-Aryan civilization” primarily from the perspective of its spiritual organizing principles or his extrapolative interpretation of them, seen in his 1934 book Revolt Against the Modern World.

From a certain perspective, Evola’s philosophy sought to recreate in earthly existence the dimensions of spiritual battle emanant from myth, oral tradition, and religious scripture. It is precisely the dangers of this approach, inherent if not pronounced, that have resurrected Evola’s reputation on both the intellectual far-right and the anti-fascist left—the former hallows his writing as a modern manifesto and the latter as the incantation of an evil “wizard behind the curtain.”

These passions, rather than critical reading of Evola (which is not always absent), render him a source of fascination. Indeed, mere mention of his name summons charges and countercharges, usually falling into two categories: those who embrace his work resist nearly any effort at classification and those who presume to oppose it rush toward classification. Neither, in my view, suffices. Both approaches beckon the surface politics that Evola claimed, not always convincingly, to oppose. I know of few twentieth century philosophers—classical conservative Leo Strauss is one—who have done a fuller job ensuring their posterity of mystique.

The earliest English translation of Evola, who wrote in Italian, was The Doctrine of Awakening with British publisher Luzac & Co. in 1951. A more popular work, The Metaphysics of Sex, did not follow until 1983 from Inner Traditions, with future translations of his books arriving from that press in the 1990s and early 2000s. Except for readers versed in Italian, the esotericist was not much read until the present generation. Today, Evola’s is a rare headline-making name among esoteric philosophers because of references to him by American rightwing activist Stephen K. Bannon and Russian nationalist Alexander Dugin.

Asof this writing, Russian politico-mystic Dugin dotes on a mélange of nationalist, occult, and Traditionalist ideas like Evola’s and those of French intellectual René Guénon (1886–1951). Guénon was a powerful and formative force in the movement called Traditionalism (he used the term “Primordial Tradition”), which seeks esoteric wisdom within the historic faiths and disdains perceived bastardizations of ancient religious ideals within modern occult and alternative spiritual movements.

Guénon’s anti-modernist approach is a vivifying tonic against careless or burlesque adaptations of ancient religious forms. At the same time, the philosopher sometimes issued erroneous polemics of his own, such as arguing against the existence of doctrines of eternal recurrence or reincarnation in ancient traditions, although often couched, like the concept of planetary epicycles, in brilliant reasoning. If an insight can be accidental, so can an error be brilliant.

That said, there can be no dismissing the intellectual power of Guénon and many of the Traditionalist writers, a fact lost on most journalists encountering their ideas randomly when analyzing Traditionalist influence on the intellectual right in Europe or America.

The chief critique of Guénon from an informed liberal perspective arrived in 1974 from philosopher Jacob Needleman in his pioneering anthology of Traditionalist writings, The Sword of Gnosis (Penguin). In his introduction, Needleman scrutinized Guénon as a critic who read rather than read about the French philosopher, concluding: “He seems never to have considered the possibility of a Way that does not demand the immediate alteration of the conditions of twentieth-century life, but that nevertheless emanates from the same source as the recognized traditions.”

Ripples from tossed stones are not always predictable: one of Guénon’s admirers was radically ecumenical scholar of religion Huston Smith (1919–2016) whose widely read textbook The World’s Religions argued for a common core to the historic faiths and posited a universalistic spirituality—themes Guénon opposed.

Ona dimmer note, we return to Dugin, a vocal supporter of Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The nationalist philosopher selected for the symbol of his Eurasia Party the eight-pointed “chaos star” of the Illuminates of Thanateros, an international order of chaos magickians, many of whom want no association with him. Rightwing American political operative Steve Bannon, who reached out to me shortly after the publication of my first book and was a source of encouragement in the writing of my second—since Bannon’s destructive election denialism our communication has ceased—has cited Julius Evola and evinced interest in a wide range of esoteric ideas, including the metaphysics of mind causation or New Thought.

Historian Gary Lachman notes in Dark Star Rising:

As a wide-ranging esoteric scholar and practitioner, in the 1920s Evola edited an occult journal called UR, which focused on a number of magical themes. Evola contributed many articles to UR, under several pseudonyms, and one of the themes he came back to regularly was the magician’s ability to alter reality through the power of the mind alone, something, we’ve seen, that both New Thought and chaos magick are interested in. For Evola, the aim of the magician is to develop his own personal power, his will, which is a kind of force that he can exert in order to refashion the world as he would like it.

In our hyper-politicized era, many commentators find it enticingly easy to view the Traditionalists as simply a reactive political force. That is inadequate. As a thought movement, Traditionalism is not monochromatic. Its ranks, broadly speaking, include Kabbalist Leo Shaya, Vedic philosopher Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, classicist Philip Sherrard, Islamic scholars Martin Lings, Frithjof Schuon, and Seyyed Hossein Nasr, symbolist Titus Burckhardt, Catholic theologian Valentin Tomberg, and—arguably—Cardinal Hans Urs von Balthasar and esoteric Egyptologist R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz, all widely read scholars of belief, some possessed of controversy but none whose work is limited to subculture or occultism.

“On close reading,” Needleman wrote in 1974 of the Traditionalists, “I felt an extraordinary intellectual force radiating through their intricate prose. These men were out for the kill…They were clearly men ‘under authority’—but under what authority, and from where did they receive the energy to speak from an idea without veering off into apologetics and argumentation?”

In a 2020 assessment almost laughable in intellectual conceit and unrecognizable in strawman examples, Fulbright scholar Nick Burns (whose accompanying biographical note stated he is “studying intellectual history”) wrote of Traditionalism in political journal The American Interest:

As a philosophy it is entirely worthless, a confection of middle-school-level readings of Hegel, Marx, and Spengler attached to a wild caricature of ancient Persian or Indian civilization . . . The role of shadowy, esoteric, occultist ideologies has turned out to be, if initially broader than anyone would have guessed, still in the end more or less as self-limiting as could be expected. Now, imaginably, these fanatics can get back to reading their tarot cards and going to black metal shows, or whatever it is they do. [7]

Ironically—and with notable exceptions—some of the chief mangling of esoteric history and ideas emerges from mainstream letters due to under-research, apathy, and cultural disdain. Many journalists and bloggers (never mind downstream on social media) paint with a broom when a liner brush is required. As essayist Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) wrote in another context, “nothing is so firmly believed, as what we least know.”

Something in human nature, probably fear of disorder and accident, overdetermines patterns after the fact—a particular pitfall to those of us who experiment with metaphysics. This tendency also informs conspiracist reaction to secret societies. Regarding political dimensions of the occult, historical observers often overlook or misunderstand that Europe in the early twentieth century was a hothouse of ideas—political, scientific, cultural, and occult—all of which crisscrossed through every movement, whether democratic, fascistic, liberal, anarchistic, conservative, including those that ostensibly rejected religious underpinnings, such as communism and socialism.

The metaphor of Lucifer or Satan was, for example, embraced in the late nineteenth century by some social democrats, socialists, anarchists, and feminists because it was seen as the post-Romance image of the rebel and purposeful malcontent. [8] In 1894, Sweden’s Social Democrats issued Lucifer, a “worker’s calendar.” Never one to go gently, Blavatsky herself inaugurated a journal called Lucifer in 1887; it ran for a decade after which it got redubbed with the less-than-thunderous title, The Theosophical Review.

Bolshevik movements seized upon the mass rally, imposing banner, heroic statue, and badge, even as such things had their earliest forms in Hellenic and Baltic pagan antiquity, because they celebrated the human form and, hence, idealized the image of the worker. The hammer-and-sickle itself was designed in its official form in 1918 by artist Yevgeny Kamzolkin, who was not a communist but a member of the mystical artists’ circle, Society of Leonardo da Vinci. In occult revivalist vein, the artist used the hammer of the Slavic thunder god Svarog and the sickle of the earth goddess Mara. [9]

Asnoted, archetypal symbols are part of any on-the-march political movement. This turns us to psychologist Carl Jung, sometimes accused of a too-accommodating stance toward early Nazism. This indictment hinges partly on Jung’s political maneuverings to balance between Nazi blacklists and continued international membership of Jews in psychological organizations within which he was active from Zurich. Jung, operating as Agent 488, also created a personality profile of Hitler for Allen Dulles at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), precursor to the CIA.

“Shortly after the war,” wrote venerable journalist Christopher Dickey in 2018, “Allen Dulles told one of Agent 488’s longtime disciples, ‘Nobody will probably ever know how much Professor Jung contributed to the Allied Cause during the war, by seeing people who were connected somehow with the other side.’ But Dulles said there was no way to reveal them: Jung’s services were ‘highly classified,’ they ‘would have to remain undocumented,’ and so they are.” [10]

In a 1938 interview, published in the February 1942 issue of Omnibook Magazine, the scholar of archetype and myth remarked,

Hitler’s power is not political; it is magic. To understand magic you must understand what the unconscious is. It is that part of our mental constitution over which we have little control and which is stored with all sorts of impressions and sensations; which contains thoughts and even conclusions of which we are not aware…Now the secret of Hitler’s power is not that Hitler has an unconscious more plentifully stored than yours or mine. Hitler’s secret is twofold; first, that his unconscious has exceptional access to his consciousness, and second, that he allows himself to be moved by it. He is like a man who listens intently to a stream of suggestions in a whispered voice from a mysterious source, and then acts upon them.

That this “stream of suggestions” included mythical symbols and concepts is not surprising; only their absence would be.

For clarity, I must add a word about magician Aleister Crowley’s controversial activities during wartime; which, with respect to controversy, differed little from other periods in the occultist’s life. Several biographers have wrestled with whether Crowley functioned as a spy for one side or another. The answer is elusive.

During World War I, Crowley lived in New York City with few sources of income. Proclaiming himself an Irish nationalist, he wrote bombastic, pro-German articles for a weekly called The Fatherland. Some British commentators denounced him as a traitor to the Allied cause. But several biographers, including Richard B. Spence, Tobias Churton, and Lawrence Sutin, have presented evidence from intelligence files and correspondence suggesting that Crowley was actually employed by British intelligence to write purposefully absurd pieces in order to sully the pro-German position. Crowley later claimed as much himself.

Twentieth century intelligence authorities from time to time showed interest in occultists either for propaganda purposes or in hopes they could penetrate certain innards of enemy or foreign thought, since occult groups were frequently international in activity. That Crowley was in dire need of funds suggests a motive for his activities.

Crowley generally stood aloof from overt politics although there exist inconclusive letters and claims that during Hitler’s rise he sought to place a copy of The Book of the Law in front of the future führer as a potential exemplar of his radically self-determinative philosophy of Thelema (Greek for “will”), which Crowley insisted was free from racial animus. Following Karl Germer’s arrest in 1935, any such chimeras burst on the rocks of reality. Crowley then tried to tailor Thelema’s appeal to British war needs, with little official interest.

In 1941, the magician wrote a pamphlet of poems for Allied victory titled, “Thumbs Up!” It was a natural extension of wartime patriotism and self-interest. He privately printed 100 copies; a signed edition appears in the special collections of the New York Public Library. Crowley apparently offered his services to British Intelligence during World War II but no need for them was found, especially with the capture of Rudolf Hess after his misbegotten flight to Scotland in 1941, when the Allies held a prisoner who could provide whatever information was significant about occult groups around the Nazis.

Although occultism has a calico history across modern politics, intermingling with a myriad array of movements, only a few of which I have noted here, evidence for a Nazi-occult connection exists more in the proclivities of the observer than the complexities of historicism.

This article is adapted from the author’s Modern Occultism (2023).

Notes

[1] For a well-contextualized critique of this issue, see “Mythological and Real Race Issues in Theosophy” by Isaac Lubelsky, Handbook of the Theosophical Current edited by Olav Hammer and Mikael Rothstein (Brill, 2013).

[2] Inside the Third Reich by Albert Speer (Macmillan, 1970).

[3] This passage is from Goodrick-Clarke’s now-classic The Occult Roots of Nazism (New York University Press, 1992). Goodrick-Clarke’s title is odd, and prone to misunderstanding, insofar as his vital study rebuts willful or excessive interpretations of occult influences behind Nazism.

[4] E.g., see Aleister Crowley: The Beast in Berlin by Tobias Churton (Inner Traditions, 2014).

[5] “The original Indiana Jones: Otto Rahn and the temple of doom” by John Preston, The Telegraph, May 22, 2008.

[6] Dark Star Rising: Magick and Power in the Age of Trump by Gary Lachman (TarcherPerigee, 2018). Lachman’s book—which is singularly outstanding—attracts attention online from several who urge it upon me as a perceived rejoinder. As Gary notes within, I commissioned, titled, and published the book.

[7] “The Occultists Who Almost Ran Your Country,” May 9, 2020.

[8] See Per Faxneld’s masterful study Satanic Feminism: Lucifer as the Liberator of Women in Nineteenth-Century Culture (Oxford University Press, 2017).

[9] The Occult Roots of Bolshevism: From Cosmist Philosophy to Magical Marxism by Stephen E. Flowers (Lodestar, 2022).

[10] “The Shrink as Secret Agent: Jung, Hitler, and the OSS,” The Daily Beast, October 22, 2018.

Great article, though I feel your learned (and useful) explication somewhat undermines your title (as does Kurlander’s book). Evans’ article (which I didn’t re-read) seems to be on solid ground. Consider this quote from Kurlander on parapsychology which could be applied to some aspects of the MAHA-adjacent psychedelic movement today:

“They were popular manifestations of a ‘scientific esotericism' that sought legitimacy within the scientific establishment and across a broader public. Despite attacks by state officials, liberals, even conservative religious groups, occultism and border science continued to grow in popularity, becoming 'not only an upstart religion but also an upstart science.’ In producing a 'science of the soul,’ a reenchanted science that transcended both scientific materialism and traditional religion, the border sciences allowed Germans the chance to challenge the authority of both.”

Glad to see Lachman’s excellent “Dark Star” mentioned. It is seldom noticed that one of America’s preeminent essayists, Wendell Berry, is also a (“soft”) Traditionalist (and perennialist, of sorts) himself.

Occultism in Nazi ideology might be overestimated in popular culture, but it is by no means a “myth” and, in my opinion, considering the current intellectual climate, could use more intelligent analyses such as yours. Thanks.