A little book of “Hermetic Philosophy” from 1908 called The Kybalion has recently polarized online opinion. Defenders of the “true way,” if such thing ever existed, damn the slender work of popular metaphysics as fraudulent, plagiarized, or “crap.”

The facts are at once simpler and subtler. Locating them requires less in the way of caffeinated language (or seeking prestige through denunciation—our generation’s addiction) and more in the way of game investigation.

Understanding occultism in the first part of the twentieth century and our own demands reckoning with the popular or dramatized literature consumed by many seekers, including The Kybalion.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, wrote in his 1850 In Memoriam A.H.H., “Truth embodied in a tale shall enter in at lowly doors.” Lowly doors open new vistas—even for the critic. I know because I was one.

“Some Good Ideas in that Little Book”

Like many readers, I once considered The Kybalion little more than a novelty of early twentieth-century occultism, which, in part, it is. Fancifully attributed to “Three Initiates,” The Kybalion calls itself a commentary on a remote, hidden Hermetic work of the same name whose aphorisms are only quoted.

The title phrase has no known antecedent but is probably a Hellenized version of Kabbalah. Based on sales data and manifold editions, the diminutive volume is easily among the most widely read occult works of the past century.

When I discovered the book nearly twenty years ago, I regarded it as a faux-antique work of New Thought or mind-power philosophy, costumed in pseudo-Hermetic garb, and offering a handful of serviceable but not greatly significant ideas of practical spirituality. I announced all this one day to philosopher Jacob Needleman (1934–2022) who had collaborated laboriously on a privately printed translation of classical Hermetic tracts. He got a gleam and in his eye and replied, “There are some good ideas in that little book.”

Years of deeper reading into traditional Hermeticism and a return to The Kybalion validated Needleman’s assessment. My early judgment was wrong. The “little book” has earned its posterity.

Chicago “Initiates”

Although some of The Kybalion’s reference points and formulations are plainly modern, the tract is defensible as an authentic if dramatized retention of certain classical Hermetic themes.

Indeed, the book serves as something close to what it claims to be: a “Great Reconciler” of metaphysical, transcendental, and New Thought philosophies, at least as practiced in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Before saying more about the value I find in The Kybalion, let me address the question of authorship. The identity of “Three Initiates” has long been a source of contention; this can distract from the book’s significance.

The Kybalion was written and published by New Thought philosopher William Walker Atkinson (1862–1932), a remarkably energetic Chicago publisher, writer, lawyer, and spiritual seeker. I identified Atkinson’s sole authorship in my 2009 Occult America; I was not the first. I also issued an edition that year that identified Atkinson’s hand, more on which below.

Atkinson was among the most incisive New Thought voices of the twentieth century. He ran an innovative esoteric publishing house called the Yogi Publication Society from Chicago’s Masonic Temple Building. His company issued a wide-ranging catalogue of highly recognizable, compact blue hardcovers from the publisher’s offices in the twenty-one-story skyscraper, which housed Masonic meeting rooms at the top. It was built in 1892 and demolished in 1939.

For years, Web 2.0 buzzed with debate over the personas of the Three Initiates. Most documentary and contextual evidence supports that it was Atkinson writing alone. Atkinson acknowledged sole authorship in an entry in Who’s Who in America in 1912.

American occultist Paul Foster Case is sometimes identified as one of the Three Initiates, and he appears to have told as much to some of his colleagues. [1] But Case was just twenty-four when the book appeared in 1908, also at a time that he had just arrived in Atkinson’s hometown of Chicago, so I consider the collaboration unlikely, although it is possible that they corresponded about some of the book’s concepts.

It should also be noted that in traditional literature, Hermes Trismegistus addresses himself to three disciples: Tat, Ammon, and Asclepius, which may have been a source of inspiration for William Walker Atkinson’s byline (or possibly his own use of a tripartite byline).

Atkinson wrote prolifically under many pseudonyms. Three Initiates has proven his most enduringly popular but he also used names including Yogi Ramacharaka, Theron Q. Dumont, and the somewhat strained Magus Incognito.

Atkinson was a prodigious writer and aficionado of New Thought and the mind- power metaphysics that were sweeping the Western world and have since become deeply entrenched in American spiritual life. His work exposed tens of thousands of early twentieth-century readers to esoteric spiritual and psychological ideas, which they might not otherwise have had wide opportunities to encounter. He wrote at least thirteen books under the byline Yogi Ramacharaka alone.

Some observers tag these works ersatz Vedism, novelty yoga, and phony Swamism. And there is, of course, justice in that verdict. But it is likewise true that this enterprising man introduced many people to variants of Vedic and yogic ideas, which would not explode across the American scene until the mid-to-late 1960s.

Traditional gurus, such as Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902), had visited America prior to Atkinson’s calico adaptations. But his popular work, like world-traveled occultist Madame H.P. Blavatsky’s (1831-1891), helped prime Americans for the wave of spiritual teaching from the East that was soon to come, especially with relaxed immigration laws instituted in 1965.

When Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1917–2008), for example, traveled to the U.S. in 1959 to teach Transcendental Meditation—an authentic technique from Vedic tradition—large swaths of the public, and certainly those within the metaphysical culture, were able to receive and understand what Maharishi and others who followed were offering. Never underestimate the power of novelty—or “lowly doors”—to pose possibilities, whet appetites, and prime interest.

Thematic Hermetics

More important than The Kybalion’s dramatic framing is how the book highlights ideas about mind, matter, and thought creativity, some of which demonstrate resonance with philosophical Hermetica.

The Kybalion is not merely, or at least not only, modern New Thought clothed in antique conceit; rather, the book connects readers, however tenuously, to late-ancient Hermetic themes of correspondence, development of psyche, scale of creation, and an all-creative Overmind.

Although Atkinson relied on several sources—including the work of accomplished nineteenth-century occult writer Anna Kingsford (1846–1888) [2]—he was probably drawing upon the seminal Hermetic translation, Thrice-Greatest Hermes by G.R.S. Mead (1863-1933), which appeared in 1906, two years before the Chicagoan’s dramatization.

Mead was a scholar of ancient mysticism and one-time secretary to Madame Blavatsky, a figure whom Atkinson revered. (The influence of her 1888 opus The Secret Doctrine is evident at several points in Atkinson’s work.) Mead’s translation of the Hermetica, while turgidly worded in late-Victorian prose, and sometimes almost purposely written as if to assume an antique affect, was then among the few sources of Hermetic ideas in English.

New Thought—and Old

With a skilled and discerning eye, Atkinson identified and distilled insights that paralleled the sturdiest aspects of New Thought, a field in which the writer-publisher was steeped. Atkinson used his considerable curatorial abilities to produce a marriage of ancient and modern psychological insights.

Atkinson focused primarily on the veritable Hermetic principle that Mind is the Great Creator. According to Hermetic literature, or most readings of it, a supreme Mind, or Nous, uses as its vehicle a threefold process consisting of: 1) subordinate mind (demiurgos–nous), 2) word (logos), and 3) spirit (anthropos), concepts that echo, albeit distantly, in Atkinson’s work.

The Kybalion is structured around “Seven Hermetic Principles,” which correspond to the Hermetic concept of “seven rulers” of nature. Man, we are told in book I of the Corpus Hermeticum, “had in himself all the energy of the rulers, who marveled at him, and each gave him a share of his own nature.” [3]

Atkinson is particularly supple in adapting the Hermetic conception of gender, in which the masculine (conscious mind, in Atkinson’s terms, and original man in the Hermetica) impregnates the feminine (subconscious mind to Atkinson, and nature in the Hermetica), to create the physical world.

Further still—and this is vital to the book’s usefulness—The Kybalion ably ventures a theory of mind causality. The book explains why, from its metaphysical premises, our minds appear to possess formative, creative abilities; and yet, even as we evince powers of causation, we are also subject to limits of physicality, mortality, and daily mechanics.

As noted in Atkinson’s chapter “‘The All’ in All,” the individual may wield traits of a higher causative Force—but that does not make the individual synonymous with that Force. Man, the book counsels, may accomplish a great deal within given parameters, including transcendence of commonly presumed limitations, influence over the minds of others, and co-creation of certain circumstances; but the book reminds the idealist that we bump against physical parameters even as we are granted the capacity, within proscribed framing, to imitate the Power that set those parameters. In classical Hermeticism, there exists possibility of rising through the seven spheres of creation, based on the ancient conception of the seven planets, to grow increasingly free of restrictions placed on human creative capacity.

Atkinson also offers compelling philosophical definitions of concepts of rhythm, polarity, paradox, compensation, and aforementioned “Mental Gender,” or the notion that nonbinary traits occupy every mind and combine to create.

In a sense, the philosophy found in The Kybalion is a modern application of Hermeticism, Neoplatonism, Transcendentalism, and New Thought. The book further attempts, however fitfully, to correspond its ideas to the early twentieth-century’s nascent insights into quantum mechanics and the “new physics,” which gained currency in the decades following its publication.

In this sense, the author exaggerates only slightly when he writes: “We do not come expounding a new philosophy, but rather furnishing the outlines of a great world-old teaching which will make clear the teachings of others—which will serve as a Great Reconciler of differing theories, and opposing doctrines.”

“Like Is Understood By Like”

The overall spirit of The Kybalion can be traced to book XI of the Corpus Hermeticum—the Renaissance-era translation that brought Hermeticism into modern awareness—in which Hermes is told by Supreme Mind that through the uses of imagination he can discover the workings of Higher Creation: “If you do not make yourself equal to God you cannot understand Him. Like is understood by like.” [4]

Hermes is told to use his mind to travel all places, to unite opposites, to know all things, to transcend time and distance: “Become eternity and thus you will understand God. Suppose nothing to be impossible for yourself.”

Hermeticism, at least as it has reached us, teaches that we are granted a Divine birthright of boundless creativity and expansion through the imagination or psyche. This teaching is central to Hermetic philosophy and its modern adaptation in The Kybalion.

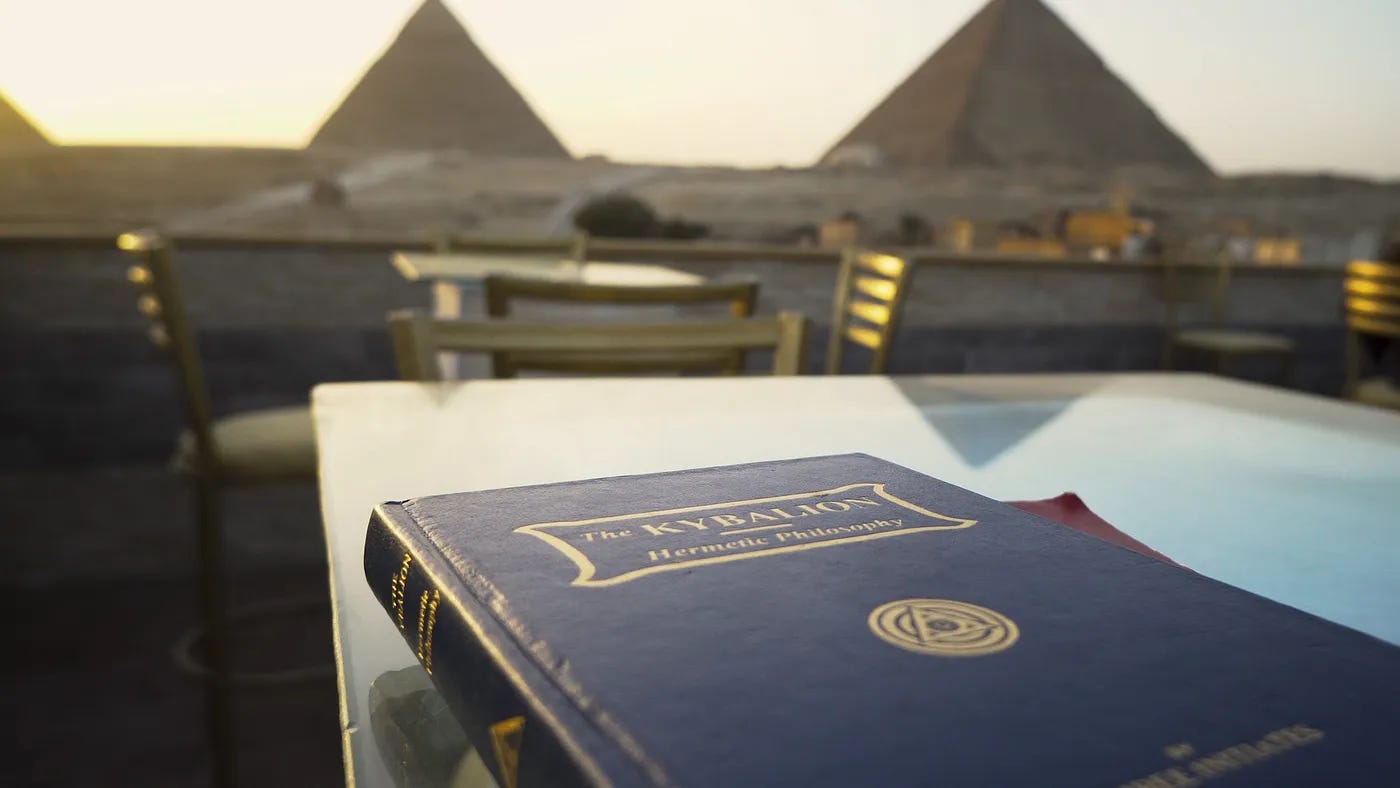

In closing, I must note that my interest in the book is not impersonal. In 2022, I hosted, cowrote, and produced a feature documentary about The Kybalion directed by Emmy-nominee Ronni Thomas and shot on location in Egypt. The movie premiered as the #3 documentary on iTunes, of which I am proud.

Whatever shapes it assumes or byways it travels, Atkinson’s minor masterpiece is not fading away. As generations of readers have found, the book’s “lowly doors” open to unexpected territory.

Notes

[1] See Paul Foster Case: His Life and Works by Paul A. Clark (OHM, 2013).

[2] Credit is due historian Mary K. Greer for this insight. Important documentary forensics are also contributed by scholars Philip Deslippe (The Kybalion: The Definitive Edition, TarcherPerigee, 2011) and Richard Smoley (The Kybalion: Centenary Edition, TarcherPerigee, 2018). I published both works.

[3] Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation with Notes and Introduction by Brian P. Copenhaver (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

[4] This quote and the next are from The Way of Hermes: New Translations of The Corpus Hermeticum and The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius by Clement Salaman, Dorine van Oyen, William D. Wharton, Jean-Pierre Mahe (Inner Traditions, 2000).

___________

Watch our July 2025 exchange about The Kybalion and more on Killah Priest Podcraft:

Thank you for this very elegant summary. as with many of your pieces, I have printed it off for myself. (this is not to reproduce it for others so much as to hedge against the possibility of the internet exploding, the ethernet vanishing)

on a by word, I have to comment that “Like Is Understood By Like” is the fundamental principle of Homeopathy, a much undervalued art. Hahnemann used Like Cures Like, but in fact “Like Is Understood By Like” is an extremely compelling difference in nuance. Thank you so much for introducing me to it.

Hey Mitch, I've dabbled in Alchemical studies over the years and if I've come across this book I totally missed it.

I work at a public library and literally a couple hours after I read this article a Spanish speaking patron asked me for a Spanish language version of this. We had one in the system, and I kinda got goosebumps. Guess it just went to the top of my to-read list! (I'm also 19 days into the 30 day challenge!!!)