What is simple is typically made out to be obscure. . . —Hegel, 1810 [1]

The problem with religion is one of simplicity. Initial experience and insight—sometimes ensconced deep in antiquity and other times occurring through modern habits—are codified into strictures, concepts, and laws.

The same process plays out in breakaway, reformist, or alternative movements initially founded to elude this reification.

My effort, seen recently in Practical Magick and now this essay, is to consider, using admittedly fragmentary forms that have reached us, what extra-physical ideas and contacts meant to humanity’s deep-ancient ancestry prior to centuries-long, sometimes millennia-long, conditioning, social filters, and redefinition, resulting in what most contemporary people consider the traditions.

I take as my topic the most controversial religious subject in Western life: the presence and meaning of Satan and, indirectly, of Satanism, a modern concept, as an independent path.

The Disturber

My query opens with an observation, easily overlooked, by controversial Jewish scholar Friedrich Weinreb (1910-1988). In his 1963 exegesis Roots of the Bible, Weinreb observes: “The word Satan really means ‘disturber’. . .” [2]

The earliest Abrahamic concept of Satan is rooted in the Hebrew השטן (ha-sataan), literally “The Satan” or the adversary (sometimes the prosecutor or opposer), or the Latin-derived term Lucifer, or light bringer (originally a condemnation of the ancient king of Babylon as a falling star in Isaiah 14:12). Weinreb’s definition is sui generis but entirely defensible.

He further notes:

One can oneself be a god, fix standards for oneself, decide for onself on life and death, on development or stagnation. It is for this reason, according to ancient lore, when they [Abraham and Isaac] were on their way to Moria, Satan advanced towards them.

Weinreb’s considered term “ancient lore” is where we begin digging. Nowhere in Genesis 22 does Satan appear or attempt to intervene when Abraham, under command of Yahweh, takes his only son Isaac to Mount Moriah to be sacrificed.

A deeper and more heterodox narrative of the Disturber’s intervention appears in works of Rabbinic and Talmudic commentary—and a debated “lost book” of the Hebrew Bible. Within this “underground history” resides a deeper and fuller texture of the ur-myth on which Western modernity stands.

Three Days Unknown

“Centuries ago,” writes twenty-first-century scholar of Jewish folklore Eli Yassif, “sages and preachers tried to ‘fill’ the gaps in the biblical story of Isaac's near-sacrifice. The largest of the gaps lies between two sentences that dryly describe Abraham and Isaac's journey to the site of the sacrifice.” [3]

Yassif continues:

What happened during those three fateful days? Is it possible that nothing happened between the father and his son being led to sacrifice? Is it possible that Isaac did not utter a word, or grimace? Did the father not twinge with doubt as he set out, or display grief about the impending loss of his beloved boy?

Several possibilities exist. The most controversial source for discerning the “in between” days in Genesis 22 is a confounding work, at least twice seemingly referenced in Scripture, and emerging with arguable legitimacy during the late Renaissance, Sefer Hayashar or The Book of the Righteous. Before considering the apocryphal book, I rely upon more traditional Talmudic and Rabbinic scholarship.

As is widely known, Abraham is tested in his loyalty when asked to sacrifice his only son, thirty-seven-year-old Isaac. The elderly patriarch is unlikely to bear another. Even facing such tragedy, the forefather prepares to give everything—only to be stayed at the last moment by an angelic hand. The story has generated massive existential controversy. As a child raised in conservative and orthodox synagogues, I recall my older sister, Nina, objecting to the test. Satan agrees with Nina.

Within the Babylonian Talmud tract Midrash Tanchuma, Vayera 22, passages 9-12, appears a little-known encounter between Satan, Abraham, and Isaac on the trek to Mount Moriah, site of Isaac’s intended death. Satan stops Abraham and asks what he is doing:

Satan appeared before him on the road in the guise of an old man and asked: “Whither are you going?” Abraham replied: “To pray.” “And why,” Satan retorted, “does one going to pray carry fire and a knife in his hands, and wood on his shoulders?”

Abraham, perhaps wishing to thwart the unknown interloper, lies to him. Satan sees through the lie. “The satan in the Hebrew Bible never lies,” observes Esther J. Hamori, professor of Hebrew Bible at Union Theological Seminary. [4] Satan challenges Abraham:

Why should an old man, who begets a son at the age of a hundred, destroy him? Have you not heard the parable of the man who destroyed his own possessions and then was forced to beg from others?

Abraham insists that he is only following the word of God. Seeing that the elder is unreachable, Satan moves on to Isaac:

Satan departed from him and appeared at Isaac’s right hand in the guise of a youth. He inquired: “Where are you going?” “To study the law,” Isaac replied. “Alive or dead?” he retorted. “Is it possible for a man to learn the law after he is dead?” Isaac queried. He said to him: “Oh, unfortunate son of an unhappy mother, many days your mother fasted before your birth, and now this demented old man is about to sacrifice you.” Isaac replied: “Even so, I will not disregard the will of my Creator, nor the command of my father.”

In his last-ditch effort, the Disturber on the third day conjures a river to block the path of the faither-son—but with God’s help with barrier dries up and they reach their destination.

The conventional reading of the story posits Satan as disrupter of God’s will—or more likely an agent of it—common themes in Jewish Scripture, commencing with Satan’s conflation—both in Rabbinic commentary and later cultural archetype—with the serpent in the garden. But conventional readings are often tone-deaf to deeper considerations, as probed in the Talmudic tract.

When revisiting the familiar framing of the serpent in Genesis 3, to which we return, virtually any translation demonstrates that not only is the serpent’s argument based in truth—the couple does not perish for eating the apple, and their eyes are, in fact, opened to good and evil (indeed, some scholars contend that the garden’s two trees, the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and the Tree of Life, are the same)—but also that Eve, contrary to a shibboleth about feminine nature, does not seduce Adam, who requires little coaxing. The serpent even suggests, as augmented in other texts, that Yahweh displays cruel hypocrisy by forbidding intellectual illumination, even as its availability sits in the garden’s midst.

As magickal scholar

has recently written of the garden: “The same division that created suffering also makes freedom possible . . . The eating of the fruit wasn’t the end. It was the first breath of the Great Work.”“Comely and Well Favored”

Having considered the three “lost days” from a Talmudic perspective, I now turn to a more unconventional—but no less intriguing—source, the apocryphal Sefer Hayashar itself.

Chapter twenty-three of the contested book retells the Abraham-Isaac-Satan story, but with a more erotic quality when Satan confronts Isaac:

And Satan returned and came to Isaac; and he appeared unto Isaac in the figure of a young man comely and well favored. And he approached Isaac and said unto him, Dost thou not know and understand that thy old silly father bringeth thee to the slaughter this day for naught? Now therefore, my son, do not listen nor attend to him, for he is a silly old man, and let not thy precious soul and beautiful figure be lost from the earth. [5]

Again, son and father push past the intruder.

Sefer Hayashar is (arguably) noted twice in Scripture and forms the subject of fitful debate in the Talmud, as noted by independent (some would say heterodox) scholar James Scott Trimm: “The Talmud discusses the identity of Jasher but also fails to offer us much real direction. In b.Avodah Zarah 25a several theories for the identity of the Book of Jasher are proposed.” [6]

Trimm further notes historical corroboration of such an ancient book by Roman-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (c. 37–c. 100 A.D.):

In his own recounting of the event of the prolonged day of Yahushua [Joshua] 10 the first century Jewish Roman historian Josephus identifies the Book of Jasher mentioned by Yahushua as one of “the books laid up in the Temple” (Ant. 5:1:17). Thus the Book of Jasher was known to Josephus and was known to be among the books laid up in the Temple in the first century.

At least two direct references—and one further debated reference—to Sefer Hayashar appear in the Bible.

Joshua 10:13 states:

And the Sun stood still, and the Moon stayed,

until the people had avenged themselves on their enemies.

Is this not written in Sefer HaYashar?

2 Samuel 1:18 states:

To teach the sons of Judah [the use of] the bow. Behold, it is written in the book of Jasher.

A third—and questionable—allusion may appear in 1 Kings 8.

The first two references appear to confirm the “lost book” as a work of authentic Biblical vintage. But contention swirls. Medieval Jewish sage Rashi (c. 1040-1105)—who commands canonical authority—suggests that the Joshua and Samuel passages may refer more generally to the Book of Genesis in the Septuagint, the earliest Greek translation of Jewish Scripture.

Hence, there is question over whether the Biblical references to Sefer Hayashar stand up. Just as there is debate over whether Sefer Hayashar is properly considered a “lost book” at all or is, rather, simply a commentary produced in its earliest form in Hebrew in 1625 in Venice. The 1887 English translation from which I quote, issued by Salt Lake City publisher J. H. Parry & Company, uses the date 1613.

There is no settling this debate. But the alternate narrative I highlight possesses undeniable historical context based on Talmudic sources alone.

Leavening Satan

There exists no evidence—at least none I have found—of a schismatic cult of ha-sataan veneration among ancient Jews. That said, it bears noting that ancient Judaism was not exclusively monotheistic.

“Previous studies of theophoric [God-bearing] names,” writes historian and journalist Ariel David, “have already given support to the widespread scholarly conclusion that the ancient Hebrews, particularly in the Kingdom of Israel, were far from strict monotheists, as YHWH [Yahweh] was only one of several tutelary deities who was attached to baby names.” [7]

Ancient Jews in Northern Israel—like “pagans” or backwater villagers in the Roman Empire—tended more toward polytheism than their more traditionally situated countrymen. Across generations, this changed and monotheism grew more the norm.

In the Babylonian Talmudic tract Bava Bathra (“The Last Gate”) 16a, passage 9, appears this leavening note about Satan expressing gratitude toward the prophet Samuel: “Rav Aḥa bar Ya’akov taught this in Paphunya [a town of Babylonia], and Satan came and kissed his feet in gratitude for speaking positively about him.” [emphasis added] Those interested in petitionary spirituality, take note.

“Even Satan appreciated human recognition and was properly grateful for it,” write historians Hershey H. Friedman, Ph.D., and Steve Lipman in their 1999 paper, “Satan the Accuser: Trickster in Talmudic and Midrashic Literature.” [8]

Again, Friedman and Lipman:

In the Talmud (Avodah Zarah 20b), Shmuel’s father quotes the Angel of Death [Samael, often conflated with Satan] as saying: “If I did not care for the dignity of human beings, I would cut open the throat of man as [wide and gaping as] that of a slaughtered animal.” In other words, Satan prefers using the poison on the tip of his sword rather than the sword itself to kill mortals because he does not feel that people should be mutilated by death.”

Here we see Satan not exactly as humanist—but certainly a different kind of historical figure than is traditionally understood.

Bible scholar Hamori goes further: “If one can avoid transposing a later Christian image onto the character in the Hebrew Bible, one might even call him . . . admirable.” (The ellipses are not mine but appear in her original.)

“Archangel of Legitimate Resolution”

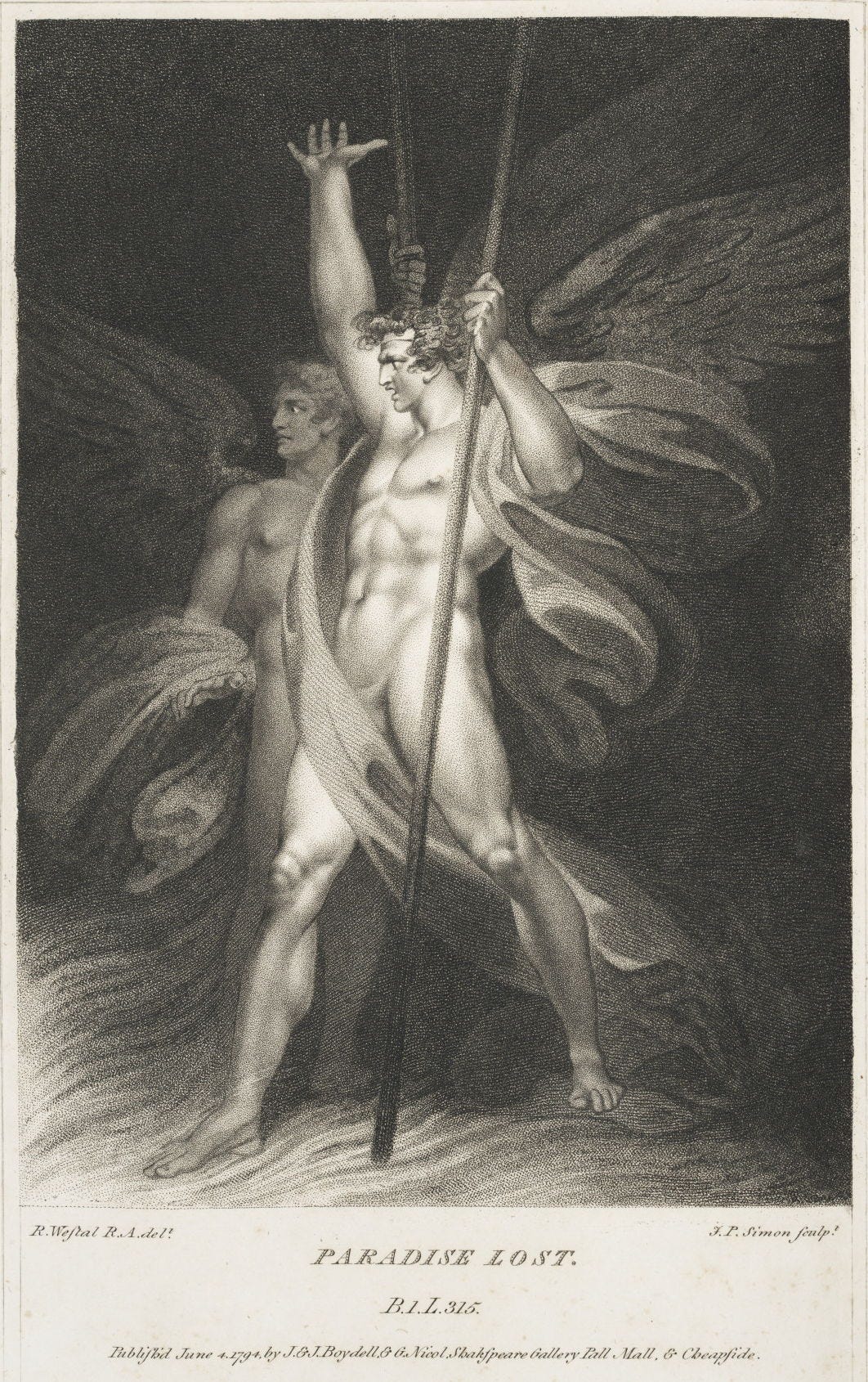

The literary-spritual-esoteric journey I describe—of Satan not as force of evil but as disturber and questioner—continued, most notably and fatefully, in the work of John Milton (1608–1674) who drew not from Rabbinic or apocryphal sources but the ambiguous and spare Genesis 3, along with a few other fragments referencing Satan in Scripture, and constructed his unparalleled Paradise Lost, which forever disrupted the image of Lucifer in the Western mind.

In Milton’s work, the monarch of fearful depravity—so culturally conditioned centuries later—is restored to a figure of defiant and even admirable rebellion, at least in the opening chapters, particularly books one and two. Milton’s epic presents the Dread Rebel, who is unbowed following his defeat and ejection from heaven, as a diabolical optimist: “The mind is its own place, and in it self / Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.” Satan’s minions mirror his formidability. The demon Mammon at one point declares, “Hard liberty before the easy yoke.”

I will share a secret. Once among I time, I was friends with political organizer / agitator Steve Bannon. No more. I could not stomach election denialism. After Steve got ejected from the White House during Trump’s first term, I messaged him the “hard liberty” quote just cited. His reply: “Dude!!!!!!!!!!!!!” Indeed.

Like Milton, visionary poet / mystic William Blake (1757–1827) blew open the Western imagination in 1790 with his verse portfolio The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in which he made the incendiary observation: “One Law for the Lion & Ox is Oppression.” Blake, you might say, gave the devil his due by positing the offending figure as a necessary counterpart to narrowly dogmatic virtue. Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell” are particularly affecting, and filled with layered observations, such as: “All wholesome food is caught without a net or a trap.”

Blake’s entry into the Western literary and ethical mind left a profound impact on the rising generation of Romantic writers and philosophers, including Percy Bysshe (1792-1822) and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797-1851) and Lord Byron (1788–1824), who sharpened the image of Lucifer as misunderstood radical.

In perhaps the most alluring and underappreciated work to emerge from “Romantic Satanism,” Lord Byron used his 1821 drama, Cain, to introduce the most jarring literary reconception of Lucifer next to Milton’s.

Byron’s Satan, who befriends the rebellious and ill-fated Cain, is persuasive and penetrating in his denial that he was the serpent in the garden and in pointing out that the serpent greeted Eve as a sexual and political emancipator—an outlook embraced by many protofeminists and political radicals of that century and the next.

Like Milton’s Satan, Byron’s dark lord is a fiery optimist and something of a socialist, who tells Cain, “I know the thoughts / Of dust, and feel for it, and with you.” Of course, the play ends with Cain’s tragic and unintended act of fratricide, leaving the reader to wonder: Are competing ideologies and human frictions the inevitable cost of awareness?

Many proto-feminists in the nineteenth century, and others during the Romantic age, did, in fact—as artists, rebels, and political agitators—view Satan as a kind of philosophical grandfather. They saw not-quite-metaphorical Satan in league with certain readings in Romantic, anarchist, and socialist literature, not as the enemy of humanity but its rough liberator.

In matters of the Satanic, Romantic and esoteric Jewish views are not in opposition. Again, historians Friedman and Lipman,: “John Milton, in Paradise Lost, has Satan saying: ‘Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.’ From what we see of the Satan described in the Talmud and Midrash, he is not all that interested in being of the ruling elite. He revels in his work as a tempter of mankind, a tester of the righteous. . . He is a trickster par excellence.”

This mythos I have traced appears esoterically in modern Western letters, fostering statements from the mouth of Satan like this one in the serialized novel Consuelo (1842-1843) by “George Sand,” popular byline of France’s clandestine woman of letters Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (1804-1876). Satan appears in a vision to the novel’s heroine, intoning:

my brother Christ loved you not better than I love you. It is time that you should know me, and that in lieu of calling me the enemy of the human race, you recover in me the friend who has aided you through the great struggle. I am not the demon. I am the archangel of legitimate resolution. . .

This is the voice below the floorboards (or locked in the attic) of Western life. It is a voice that cannot be contained—because it forever whispers, look for yourself. Or, as Milton’s Satan puts it: “Can it be sin to know?”

“My Name Is Called Disturbance”

What, finally, about the quotation in my title? It has a story of its own on which I close.

For years, like many Westerners of my generation, I have loved the 1968 Rolling Stones song “Street Fighting Man.” Recent to this writing, I discovered a cover by Ace Frehley and, perhaps because Ace enunciates differently from Mick, I picked up a lyric I had never before deciphered:

Hey, said my name is called Disturbance

I'll shout and scream, I'll kill the king

I'll rail at all his servants

The phrase would not leave me. Days after hearing it, with no indication why, I plucked from my shelf an unread copy of Weinreb’s Roots of the Bible—and began my journey.

Thank you Mick and Keith for reading the ether, as one might say, “At Her Satanic Majesty’s Request.”

Notes

[1] Hegel is quoted from a comment on Mesmerism (notable in itself) in a letter of October 15, 1810, to P.G. van Ghert (1782-1852), a student and later friend:

It is precisely the simplicity of animal magnetism which I hold to be most noteworthy. For what is simple is typically made out to be obscure . . . Its operation seems to consist in the sympathy into which one animal organism [Individualitiit] is capable of entering with a second . . . That [sympathetic] union [of two organisms] leads life back again into its pervasive universal stream.

From Hegel: The Letters translated by Clark Butler and Christiane Seiler (Indiana University Press, 1984)

[2] Weinreb’s study originally appeared in Dutch in 1963 and in English in 2021 with Angelico Press, a Catholic scholarly publisher. The fairest brief assessment I know of Weinreb’s career—which included the repugnant cloud of his collaborating with the Nazis and sacrificing the lives of his own people—appears at: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/weinreb-friedrich. As of this writing, I have not fully researched the charges against Weinreb but intend to return to this point.

[3] “Satanic Verses: An apocryphal tale tells of the inner conversation Isaac had with the devil en route to his near-sacrifice” by Eli Yassif, Haaretz, September 17, 2010

[4] “Before the satan Was Evil” by Esther J. Hamori in Evil: A History (Oxford Philosophical Concepts) edited by Andrew P. Chignell. In the Kindle edition of this anthology, Hamori’s byline is mistakenly (and, in my view, unconscionably) misspelled as Hamorip. In my twenty-seven years in trade publishing, I never permitted misspelling of a byline.

[5[ I quote from the 1887 English translation issued by Salt Lake City publisher J. H. Parry & Company. This translation is also used by Yassif.

[6] I quote Trimm from his 2008 introduction to reissue of Sefer Hayashar: “The ‘Book of Jasher’ presented in this volume was published in Hebrew in Venice in 1625, translated into English by Mosheh Samuel and published by Mordechai Noah in New York in 1840. It was Mosheh Samuel who first divided the work into chapter and verse (being 91 chapters.) A second edition of this translation was published in Salt Lake City by J. H. Parry & Company in 1887.” There also exists a spurious Book of Jasher, published 1750 in which the title is deemed the name of its author.

[7] “Names Reveal Unseen History of Biblical Kingdoms of Israel and Judah, Researchers Say” by Ariel David, Haaretz, May 12, 2025

[8] “Satan the Accuser: Trickster in Talmudic and Midrashic Literature” by Hershey H. Friedman, Ph.D., and Steve Lipman, Thalia: Studies in Literary Humor, Vol. 18, March 1999

[9] Useful and compelling overviews appear in Satanic Feminism by Per Faxneld (Oxford University Press, 2014) and The Devil’s Party: Satanism in Modernity edited by Per Faxneld and Jesper Aa. Petersen (Oxford University Press, 2012).

If you liked this article, you may also enjoy:

Anti-Serenity

I neither condemn nor elevate suffering. To generalize about a suffering person is to render him or her one-dimensional.

Paradigm-shifting, life-changing stuff, Mr. Horowitz! Thanks as always. ⚡️

Absolutely fucking delicious, Mitch. Makes me wonder if you've read Lilith: A Novel by Nikki Marmery...doesn't cover the same ground at all, but I think her book shares this viewpoint. Would love to know your thoughts!